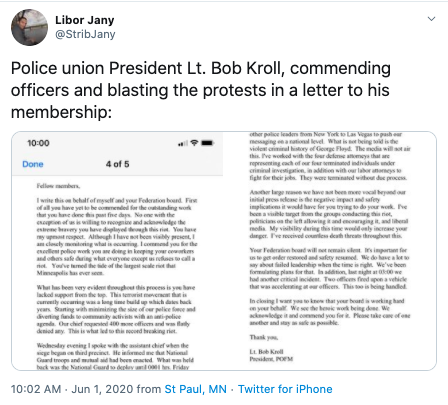

As cities worldwide erupted in protests over the death of George Floyd — a Black man who died after a white police officer knelt on his neck for about nine minutes in Minneapolis — the leader of that city's police federation sent the below-displayed email to union members. In it, he criticized journalists' and politicians' portrayal of the man whose death had sparked a global reckoning over racism in policing.

"What is not being told is the violent criminal history of George Floyd," said former Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) Lt. Bob Kroll, who represented more than 800 police officers at the time of Floyd's death. "The media will not air this."

The June 1, 2020, letter by Kroll, whom Snopes could not reach for this report and retired in early 2021, inspired a wave of claims online about Floyd's alleged arrests and incarcerations before his death — mostly among people who seemed to be searching for evidence that either the actions by the Minneapolis police officer who choked Floyd were justified, or memorials to honor him were unnecessary.

Among the most popular claims were those by the right-wing commentator Candace Owens, who, in a roughly 18-minute video that's been viewed more than 6 million times, made several accusations about Floyd's past and the events that led to his death. She said:

No one thinks that he should have died in his arrest, but what I find despicable to be is that everyone is pretending that this man lived a heroic lifestyle when he didn't. …I refuse to accept the narrative that this person is a martyr or should be lifted up in the black community. ...He has a rap sheet that is long, that is dangerous. He is an example of a violent criminal his entire life — up until the very last moment."

She claimed reporters had wrongly interpreted Floyd's death to the public by purposefully omitting details about his past unlawful behavior, and she falsely and inappropriately called police brutality a "myth" and part of some nefarious scheme by news media to polarize Americans before the 2020 U.S. presidential election.

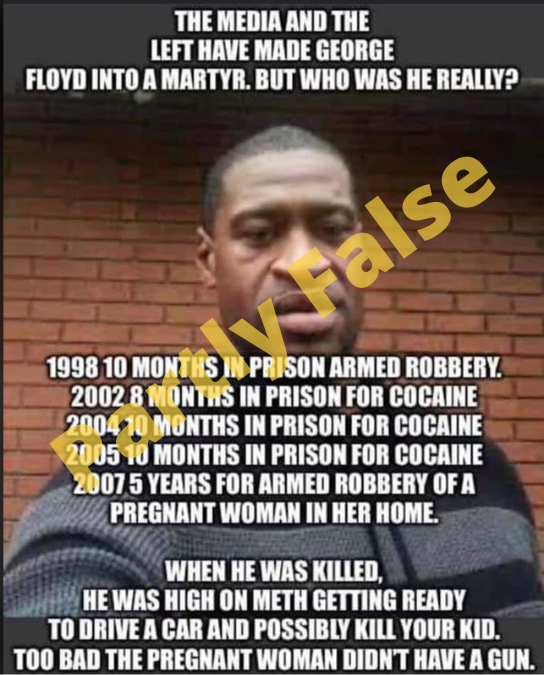

That video, as well as misleading photographs, memes like the one displayed below, and sensationalized tabloid stories about Floyd's past, prompted numerous inquiries to Snopes from people wondering if he had indeed served time in jail or prison before his death at age 46.

The claims in this meme are a mixture of true and false, as we'll document below. In brief, the alleged crimes and time periods are mostly accurate, with the caveat that Floyd was convicted of theft in 1998, not armed robbery. But the following information makes other aspects of the post misleading: Not all the crimes resulted in prison time, but rather jail sentences; no evidence suggests a woman involved in the 2007 charge was pregnant; it's an exaggeration of toxicology results to claim Floyd "was high on meth" when he was choked by a cop, and there's no proof that Floyd was "getting ready to drive a car" before his fatal encounter with police other than the fact that officers say they approached him as he sat in the driver's seat of a vehicle.

What follows is everything we know about crimes committed by Floyd — who was born in North Carolina, lived most of his life in Houston and moved to Minneapolis in 2014 — based on court records and police accounts to fulfill those requests. Additionally, this report explores the following:

- Did Floyd's past arrests and incarcerations have any effect on police officers' actions during the 911 call that led to his death?

- Was he "high on meth" when he was choked by the Minneapolis cop and died, like the above-displayed meme claims?

- How will Floyd's criminal record and autopsy toxicology results play a role in the murder trials for the police officers charged in his death?

- Why do some people draw attention to the criminal histories of non-white people killed by police?

We should note at the outset that attorney Ben Crump, who represents Floyd's family, did not respond to Snopes' multiple requests for comment, and when we reached an MPD spokesman by phone for this report, he requested an email interview but did not complete it.

Also, we should make clear that four officers involved in Floyd's death, including the cop who knelt on his neck, were fired from MPD and have been criminally charged (details below).

Snopes also has in-depth reporting on the background of Derek Chauvin, one of four former police officers charged in the case surrounding George Floyd's death. Read that report here.

Police Arrested Floyd a Total of 9 Times, Mostly on Drug and Theft Charges

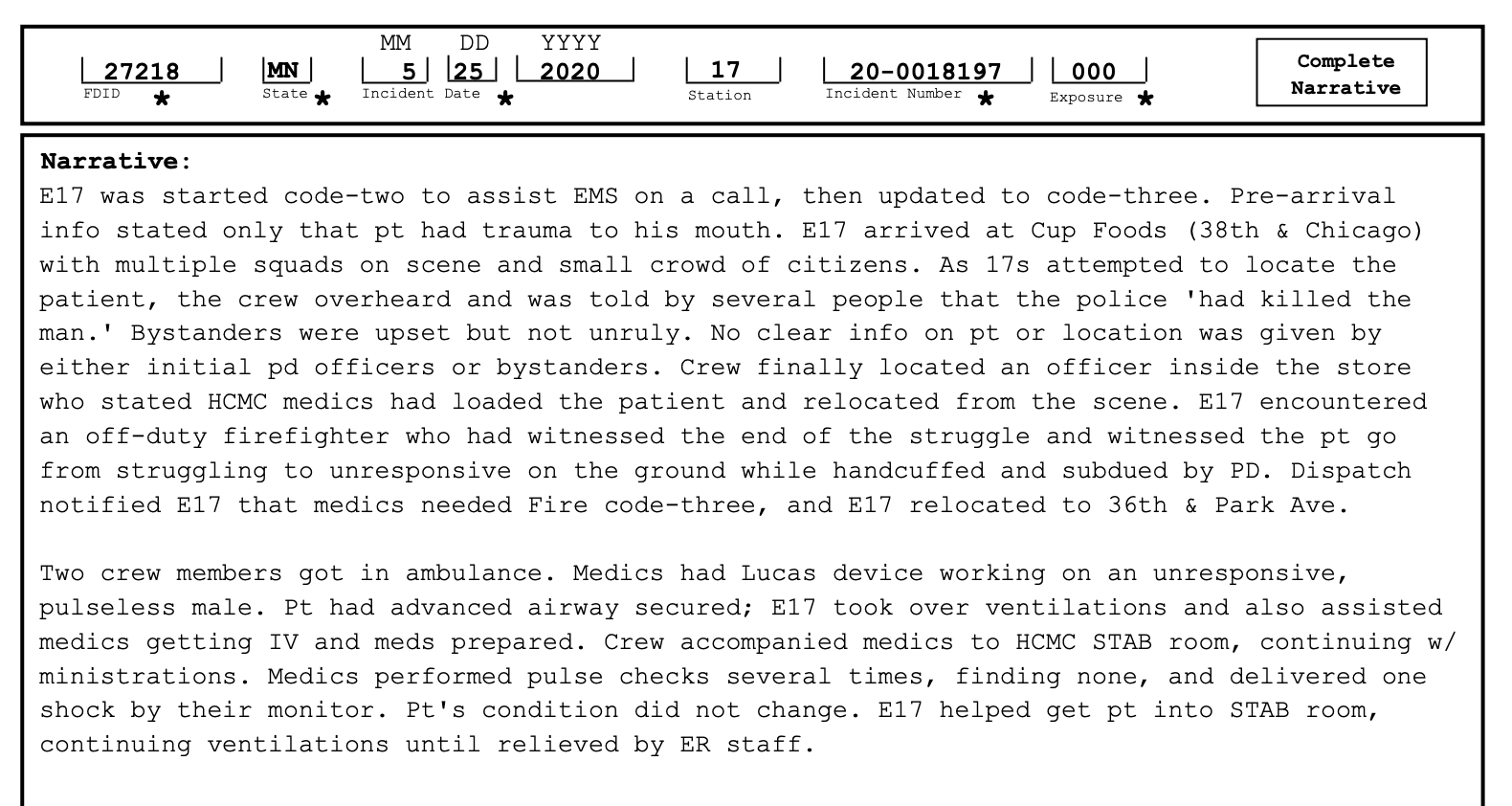

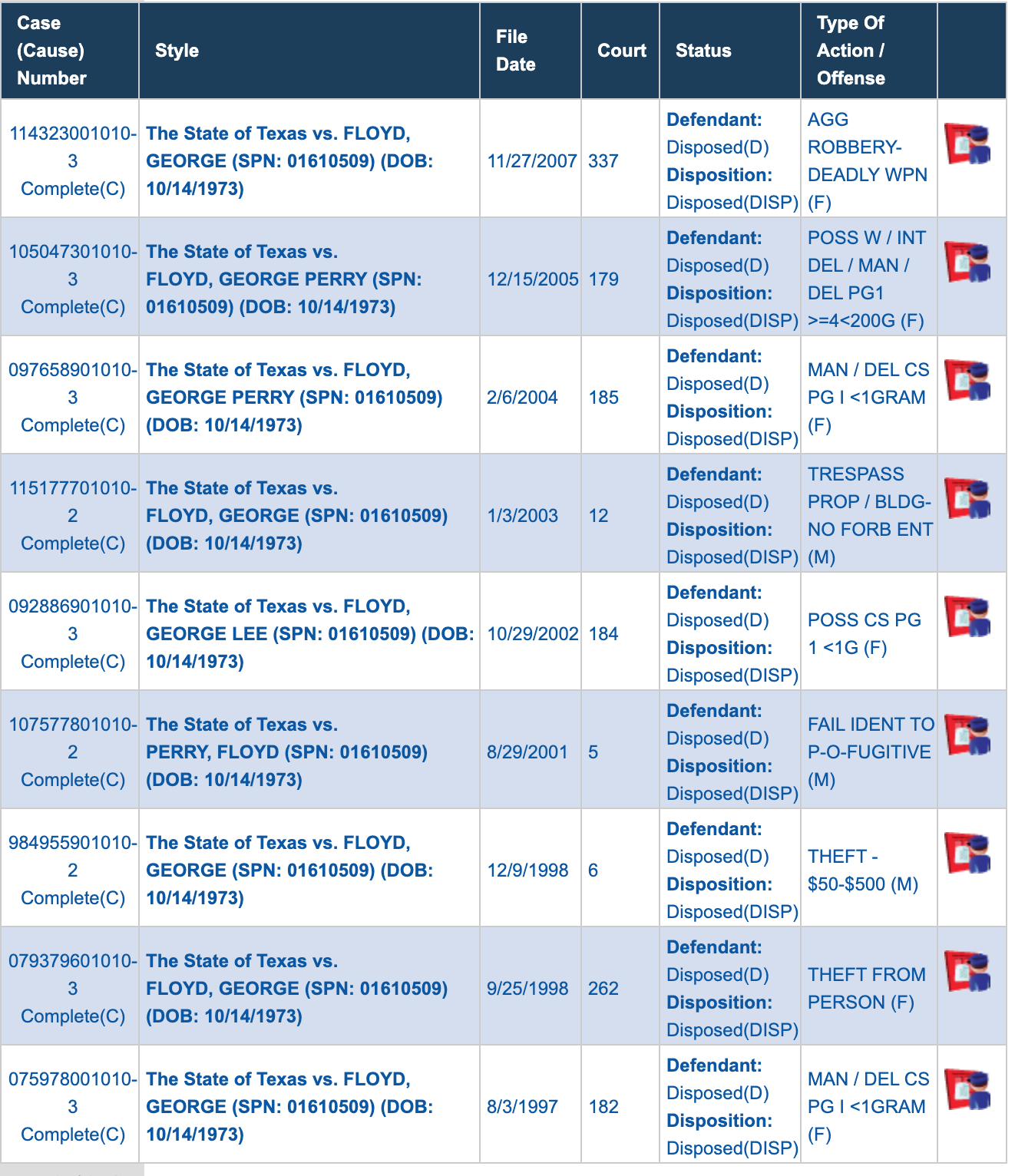

According to court records in Harris County, which encompasses Floyd's hometown of Houston, authorities arrested him on nine separate occasions between 1997 and 2007, mostly on drug and theft charges that resulted in months-long jail sentences.

But before we get into the specifics of those cases, first, some biographical details, per The Associated Press (AP): Floyd was the son of a single mother, who moved to Houston from North Carolina when he was a toddler so she could find work. They settled in what's called "Cuney Homes," a low-income public housing complex of more than 500 apartments in the city's predominately Black Third Ward. As a teen, Floyd was a star football and basketball player for Jake Yates High School, and later he played basketball for two years at a Florida community college. After that, in 1995, he spent one year at Texas A&M University in Kingsville before returning to his mother's Cuney apartment in Houston to find jobs in construction and security.

Another piece of important context while exploring how, and under what circumstances, police arrested Floyd in the late 1990s and early 2000s when he lived in Cuney Homes: On multiple occasions, police would make sweeps through the complex and end up detaining a large number of men, including Floyd, a neighborhood friend named Tiffany Cofield told the AP. Additionally, Texas has one of the highest incarceration rates in the country, per the Prison Policy Initiative, and several studies show authorities are way more likely to target Black Texans for arrests than white residents.

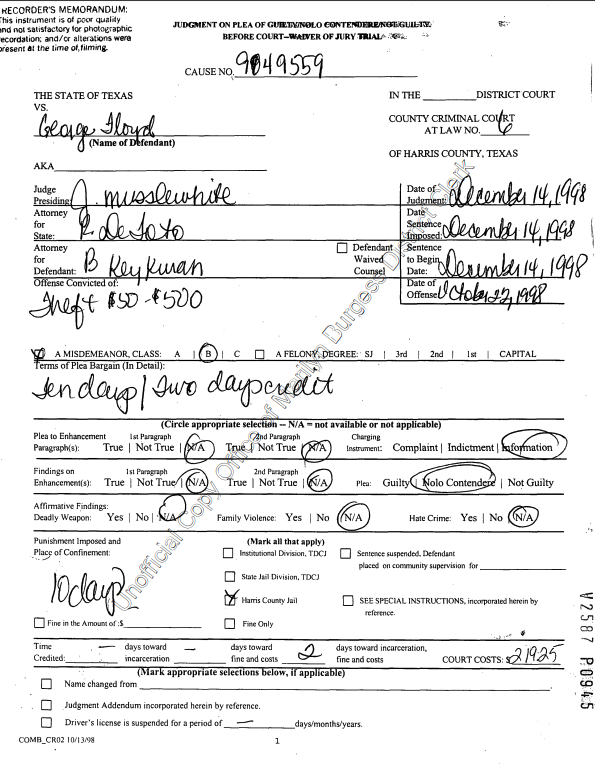

As to the details of Floyd's arrests, the first occurred on Aug. 2, 1997, when he was almost 23 years old. According to prosecutors, police in that case caught him delivering less than one gram of cocaine to someone else, so they sentenced him to about six months in jail. Then, the following year, authorities arrested and charged Floyd with theft on two separate occasions (on Sept. 25, 1998, and Dec. 9, 1998), sentencing him to a total of 10 months and 10 days in jail.

Then, about three years later (on Aug. 29, 2001), Floyd was sentenced to 15 days in jail for "failure to identify to a police officer," court documents say. In other words, he allegedly didn't give his name, address or birth date to a cop who was arresting him for reasons that are unknown (the court records don't say why police were questioning him in the first place) and requesting that personal information.

Between 2002 and 2005, police arrested and charged Floyd for another four crimes: for having less than one gram of cocaine on him (on Oct. 29, 2002); for criminal trespassing (on Jan. 3, 2003); for intending to give less than one gram of cocaine to someone else (on Feb. 6, 2004); and for again having less than one gram of cocaine in his possession (on Dec. 15, 2005). He was sentenced to about 30 months in jail, total, for those crimes.

Lastly, in 2007, authorities arrested and charged Floyd with his most serious crime: aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon.

According to police officers' probable-cause statement, which is often the basis of prosecutors' case against suspects, the incident (on Aug. 9, 2007) unfolded like this: Two adults, Aracely Henriquez and Angel Negrete, and a toddler were in a home when they heard a knock at the front door. When Henriquez looked out the window, she saw a man "dressed in a blue uniform" who said "he was with the water department." But when she opened the door, she realized the man was telling a lie and she tried shutting him out. Then, the statement reads:

However, this male held the door open and prevented her from doing so. At this time, a black Ford Explorer pulled up in front of the Complainants' residence and five other black males exited this vehicle and proceeded to the front door. The largest of these suspects forced his way into the residence, placed a pistol against the complainant's abdomen, and forced her into the living room area of the residence. This large suspect then proceeded to search the residence while another armed suspect guarded the complainant, who was struck in the head and side areas by this second armed suspect with his pistol after she screamed for help. As the suspects looked through the residence, they demanded to know where the drugs and money were and Complaint Henriquez advised them that there were no such things in the residence. The suspects then took some jewelry along with the complainant's cell phone before they fled the scene in the black Ford Explorer.

About three months later, investigators in the Houston Police Department narcotics unit "came across this vehicle during one of the their respective investigations and identified the following subjects as occupants of this vehicle at the time of their investigation: George Floyd (Driver)...," the statement reads.

At 6-foot-7, Floyd was identified as the "the largest" of the six suspects who arrived at the home in the Ford Explorer and had pushed a pistol against Henriquez' abdomen before looking for items to steal. (Nothing in the court documents suggests she was pregnant at the time of the robbery, contrary to what memes and Owens later claimed.) He pleaded guilty in 2009 and was sentenced to five years in prison. He was paroled in January 2013, when he was almost 40 years old.

We Don't Know If MPD Officers Knew of Floyd's Past Arrests and Incarcerations

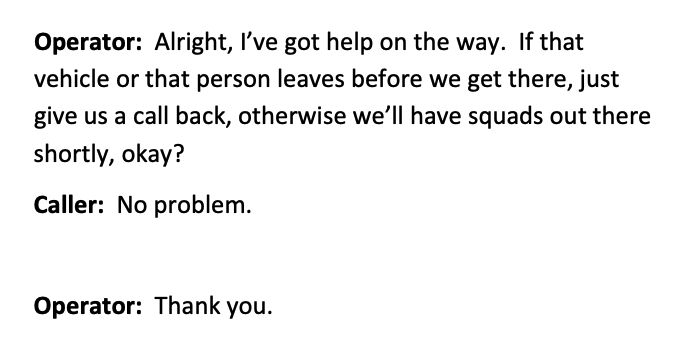

But to fully explore this, we'll lay out what happened on May 25, 2020. Around 8 p.m., someone inside a South Minneapolis convenience store called police to report that a man had used a $20 counterfeit bill to buy cigarettes, and then he ran outside to a vehicle parked nearby. The caller did not identify Floyd by name, according to the 911 transcript.

But here are some details about that call we learned after Floyd's death: The owner of the store, Mahmoud Abumayyaleh, told NPR that clerks are trained to let management know when someone uses counterfeit money, and the workers try to handle the crime themselves without cops, unless things escalate to violence. But in Floyd's case, Abumayyaleh said a teenage clerk who had only been employed for six months called 911, essentially implying the worker had not fully understood their protocol. Additionally, the owner said Floyd had been a regular customer for about a year, and he never caused any issues.

According to court documents, two MPD officers — Thomas Lane and J. A. Kueng — responded to the 911 call and, after talking to people inside the store, went to find Floyd in a parked vehicle nearby.

As Lane began speaking with Floyd, who was sitting in the driver's seat of the vehicle, the officer pulled his gun out and instructed Floyd to show his hands. Floyd complied with the order, whereupon the officer holstered his gun. Then, Lane ordered Floyd out of the car and "put his hands on Floyd, and pulled him out of the car," and handcuffed him, according to prosecutors. Then, charging documents state:

Mr. Floyd walked with Lane to the sidewalk and sat on the ground at Lane's direction. When Mr. Floyd sat down he said "thank you man" and was calm. In a conversation that lasted just under two minutes, Lane asked Mr. Floyd for his name and identification. Lane asked Mr. Floyd if he was "on anything" and noted there was foam at the edges of his mouth. Lane explained that he was arresting Mr. Floyd for passing counterfeit currency.

At 8:14 p.m., Officers Lane and Kueng stood Mr. Floyd up and attempted to walk Mr. Floyd to their squad car. As the officers tried to put Mr. Floyd in their squad car, Mr. Floyd stiffened up and fell to the ground. Mr. Floyd told the officers that he was not resisting but did not want to get in the back seat and was claustrophobic.

At that point, two other officers — Derek Chauvin and Tou Thao — arrived at the scene and tried again to get Floyd into a squad car. While they attempted to do so, he began asserting that he could not breathe. Then, according to criminal charges against Chauvin, the officer pulled Floyd out of the squad car, and "Mr. Floyd went to the ground face down and still handcuffed." The complaint continues:

Officer Kueng held Mr. Floyd's back and Officer Lane held his legs. Officer Chauvin placed his left knee in the area of Mr. Floyd's head and neck. Mr. Floyd said, 'I can't breathe' multiple times and repeatedly said, 'Mama' and 'please,' as well. At one point, Mr. Floyd said 'I'm about to die.'

A Minnesota judge released footage from Lane and Kueng's body cameras in early August 2020 — new evidence that showed their attempts to put Floyd into the squad car, and his repeated requests for the officers to consider his health. The videos also showed Chauvin kept Floyd pinned to the ground and knelt on his neck for about nine minutes, including for nearly three minutes after Floyd became non-responsive.

Then, per emergency medical technicians' and fire department personnel's accounts of the incident, medics loaded Floyd into an ambulance, where they used a mechanical chest compression device on Floyd, though he did not regain a pulse and his condition did not change.

It's unclear whether at any point before or during the call the MPD officers knew of Floyd's past arrests in Texas and, if so, whether that information at all influenced how they acted, consciously or subconsciously. MPD spokespeople did not respond to Snopes' questions about the officers' prior knowledge of Floyd before the call from the convenience store, nor did the department answer whether officers in general adjust their responses to 911 calls, or how they approach suspects, based on the criminal records of people involved.

Charging documents, police records and other court filings that lay out Floyd's criminal history are all publicly available via the Harris County District Clerk online database. Additionally, according to MPD's policy and procedure manual, which outlines everything from how officers should dress on the job to use-of-force guidelines, officers use a computerized dispatch system to handle 911 calls and often rely on computers in their squad cars to look up and document information.

All of that said, MPD Chief Medaria Arradondo said on June 10, 2020: "There is nothing in that call that should have resulted in the outcome with Mr. Floyd's death."

It's an Exaggeration of Toxicology Findings To Claim Floyd Was 'High on Meth' When He Died

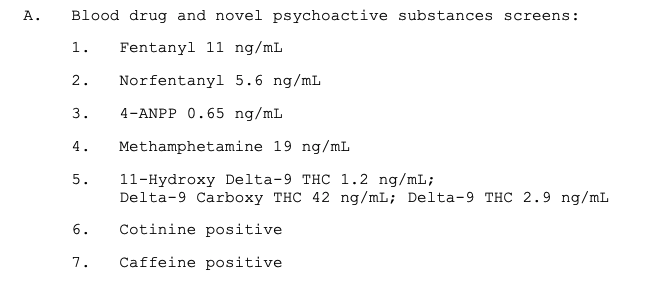

In response to one of Owens' claims — "George Floyd at the time of his arrest was high on fentanyl and he was high on methamphetamine" — as well as assertions by social media users who seemed to be in search of proof for why the MPD officers acted the way they did, here we unpack the results of Floyd's autopsy report.

The claim is two-pronged: that Floyd had meth in his system and that he was high on the drug when Chauvin knelt on his neck, choking him.

Firstly, on May 29, 2020, court documents revealed the Hennepin County Medical Examiner's investigation into Floyd's death showed "no physical findings that support a diagnosis of traumatic asphyxiation," and that "potential intoxicants" and preexisting cardiovascular disease "likely contributed to his death." (Note: Coronary artery disease and hypertension typically increase patients' risk of stroke and heart attack over years, not minutes, and asphyxia, or suffocation, does not always leave physical signs, according to doctors.)

Two days later, the county released a statement that attributed Floyd's cause of death to "cardiopulmonary arrest complicating law enforcement subdual, restraint, and neck compression" — which essentially means he died because his heart and lungs stopped while he was being restrained by police. That announcement came just hours after Floyd's family released findings of a separate, private autopsy that determined Floyd had indeed died from a combination of Chauvin's knee on his neck and pressure on his back from the other officers. (A copy of that autopsy with all of its details has not been made public.)

According to the county's postmortem toxicology screening, which is summarized below and was performed one day after Floyd's death, he was intoxicated with fentanyl and had recently used methamphetamines (as well as other substances) before Chauvin choked him.

More Specifically, Floyd tested positive for 11 ng/mL of fentanyl — which is a synthetic opioid pain reliever — and 19 ng/mL of methamphetamine, or meth, though it's unclear by what method the intoxicants got into his bloodstream or for what reasons.

But more complex is proving whether "he was high" at the time of his fatal encounter with police. While everyone's reaction to and tolerance for such drugs varies, and the effects of mixing drugs can be totally unpredictable, lab technicians say fentanyl slowly leaves users' systems, mostly via urination, over the course of three days from when they first shot up. Additionally, they consider "the presence of fentanyl above 0.20 ng/mL" — which is significantly less than the amount found in Floyd's system — to be "a strong indicator that the patient has used fentanyl," according to Mayo Clinic Laboratories.

For methamphetamines, which are typically smoked or injected, users feel an instant euphoria, and then the tapering effects of the drug last anywhere from eight to 24 hours. After that initial "rush," the amount of meth reduces in their bloodstreams and tests for the drug can be positive for up to five days. Per the University of Rochester Medical Center, the amount of methamphetamines found in Floyd's bloodstream (19 ng/mL or .019 mg/L) is "within the range" of some patients' "therapeutic or prescribed use" of the drug.

Also, Hennepin County medical examiners stated Floyd's blood levels made it seem like he had "recently" used meth in the past, not that he was peaking on a high from it, and the county investigators did not list the drugs as Floyd's cause of death, but rather as "significant conditions" that influenced how he died. For those reasons and considering the amount of methamphetamines detected in Floyd's toxicology report, it's an exaggeration of the scientific evidence to claim Floyd "was high on meth" before police choked him — though his bloodstream did test positive for the drug.

But while making that analysis, it is important to consider the insight of a group of emergency room doctors and psychiatrists, who in the wake of Floyd's death wrote in the Scientific American: "When Black people are killed by police, their character and even their anatomy is turned into justification for their killer's exoneration. It's a well-honed tactic."

Furthermore, a letter on behalf of thousands of Black doctors and health care workers in America titled "The 'Collective Black Physicians' Statement' on the death of Mr. George Floyd" stated:

Any mention of potential intoxicants of which Mr. Floyd may have been under the influence is meritless at this stage of the physical autopsy examination. In a medicolegal autopsy, the results of a urinary toxicology screen are often inaccurate. All substances must be detected and confirmed in blood and/or particular organs before it can be said that an individual was intoxicated and that death is a complication of that toxicity.

Floyd's Rap Sheet and Toxicology Results Are Likely To Play a Role in Officers' Murder Trials

We can credit history for our conclusion on this point. For example, during the murder trial of George Zimmerman — who, though not a police officer, was eventually acquitted of homicide charges in the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin, a Black teenager, in 2012 — reports of Martin's alleged truancy and petty crimes made news headlines. Similarly, people called attention to the arrest record of Alton Sterling, a 37-year-old Black man who was shot and killed by a white police officer in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 2016, as his surviving relatives filed a wrongful death lawsuit against police and the city (which remains ongoing as of this writing).

In the latest high-profile case of deadly use of force by police, all four officers — Lane, Kueng, Chauvin and Thao — were fired from MPD the day after Floyd's controversial killing and were criminally charged.

For 19-year MPD veteran Chauvin, 44, who faces the most severe charges of the four men, Hennepin County prosecutors initially charged him with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. But in early June, after Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz requested the state's Attorney General Keith Ellison to take over the case, Ellison upgraded those charges so the ex-MPD officer now faces a more severe charge of second-degree murder, in addition to the original charges brought forth by county prosecutors. (Read that latest complaint here.) He made his first court appearance on June 8, 2020, which was mostly procedural, and was held on $1.25 million bail.

Meanwhile, Thao, Kueng and Lane face charges of aiding and abetting second-degree murder while committing a felony, and with aiding and abetting second-degree manslaughter in Floyd's killing. (You can read the full charges against Thao here; Kueng here, and Lane here.) They made their first court appearances on June 4, 2020, where a judge set bail for each of them at $750,000 if they agreed to certain conditions, such as leaving law enforcement work and avoiding contact with Floyd's family. One week later, Lane, 37, posted that amount and was freed from Hennepin County jail, and his attorney told the Star Tribune he was planning to file a motion to dismiss the charges.

As of this report, all four officers were scheduled to make their next court appearance June 29, 2020, and no court proceedings have focused on Floyd's criminal history or drug use, with the exception of the charging documents that mention Hennepin County's autopsy report and toxicology findings.

Why People Draw Attention to Criminal Histories of Black Men Who Die in Police Custody

For decades, corners of the internet and journalists have highlighted the criminal records of non-white people killed by authorities or caught in viral videos, no matter the relevancy of the rap sheets.

One of the uglier examples is the case of Charles Ramsey, a self-described "scary looking black dude" who helped rescue Amanda Berry, a Cleveland woman who had been kidnapped and held hostage for years in a home near Ramsey's, in 2013. His interviews about the rescue spread like wildfire online, but then a local TV station aired a story on his criminal past (it was later removed and the station apologized).

More similar to the case of Floyd are the above-mentioned examples of Sterling and Martin, Black men who died at the hands of police and a neighborhood watch volunteer, respectively, and whose histories were trotted out in news stories after they died, seemingly as part of an effort to deny them martyrdom.

Advocates for police reform say the pattern puts unjust blame on victims of police violence and distracts the public from the most important issue at the center of these incidents: Officers too often resort to violence when dealing with citizens, especially if they are Black, indigenous, or people of color.

Kevin O Cokley, a psychology professor at the University of Texas at Austin who studies police brutality against Black Americans, explained the psychology behind the media pattern in an email to Snopes. Of people calling attention to Floyd's criminal past, specifically, he wrote:

It fits into what psychologists have called the just-world hypothesis, which is a cognitive bias where people believe that the world is just and orderly, and people get what they deserve. It is difficult for people to believe that bad things can happen to good people or to people who don't deserve it. This is because if people know that these things do happen, they have to decide whether they want to do something about it or sit by silently knowing that there is injustice happening around them.

Furthermore, his colleague Richard Reddick, an associate dean in the university's College of Education, told us in a phone interview the claims about Floyd were also a product of the era's highly polarized media environment, compounded by years of problematic storytelling by politicians and reporters that portrays Black men only as "criminal entities" instead of nuanced people. He said:

This is something that Black men are subject to quite a bit — not often seen as complex, whole human beings, who have done wonderful things and not so great things in their lives, but simply a criminal. ... This is something that seems to be very specific to Black men who are ex-judiciously murdered; we have to find a rationale, or excuse, or justification for it, no matter what it was.

In other words, he said, shifting the public narrative away from police officers' actions and onto Floyd's criminal history is a reoccurring communication strategy "that's intended to make us not see him as a victim, to dehumanize him, and to make him a caricature." People can subscribe to the "he had it coming" trope so they don't have to feel sorry for the victim of police brutality and can deny police responsibility for their actions, Reddick said. He added:

I don't trust the motivations of the folks bringing this forward. ... Of course they're asking, 'Why isn't [Floyd's criminal history] covered in the major media?' And it's because it's not relevant to this kind of story. What happened to George Floyd in Minneapolis has nothing to do with what happened to him, what he did, in 2007.

To that point, Reddick said Floyd's past arrests and incarcerations may justifiably appear in "wholesome portraits" about Floyd's life (such as this AP story), while O Cokley said the news media should not include the background in its stories about Floyd because it "has no relevance to the officer's behavior," and because "there is no standardization of the inclusion of background information on stories involving victims of police misconduct." Reddick summed up the phenomenon like this:

We shouldn't conflate the complexity of a person's life with an event that ended with their life being lost — those moments and that time is relevant, but not a criminal conviction from years prior because this is supposedly a country where, when you've served your sentence, you're now able to go rebuild your life, as what he was trying to do.

In January 2013, after Floyd was paroled for the aggravated robbery, people who knew him said he returned to Houston's Third Ward "with his head on right." He organized events with local pastors, served as a mentor for people living in his public housing complex, and was affectionately called "Big Floyd" or "the O.G." (original gangster) as a title of respect for someone who'd learned from his experiences. Then in 2014, Floyd, a father of five, decided to move to Minneapolis to find a new job and start a new chapter.

"The world knows George Floyd, I know Perry Jr.," said Kathleen McGee, his aunt (in reference to her nickname for Floyd), at his funeral on June 9, 2020. "He was a pesky little rascal, but we all loved him."