During a 31 July 2018 campaign-style rally in Tampa, Florida, President Donald Trump advocated for the implementation of stricted voter ID laws, a common topic at such events. At that rally however, Trump argued that such a move should not be seen as controversial because the act of buying groceries, a simple and regular task, also requires that Americans produce identification. “If you go out and you want to buy groceries, you need a picture on a card. You need ID,” he told the crowd.

That statement perplexed many listeners, as no state or federal law anywhere in the U.S. requires that shoppers produce identification before exchanging money for food. For the most part, criticism of the president's statement followed the New York Times’ approach, who asked and investigated the question “Has Trump ever been in the checkout line at a grocery store?” (White House press secretary Sarah Sanders later maintained that the president was referring to the purchase of beer and wine.)

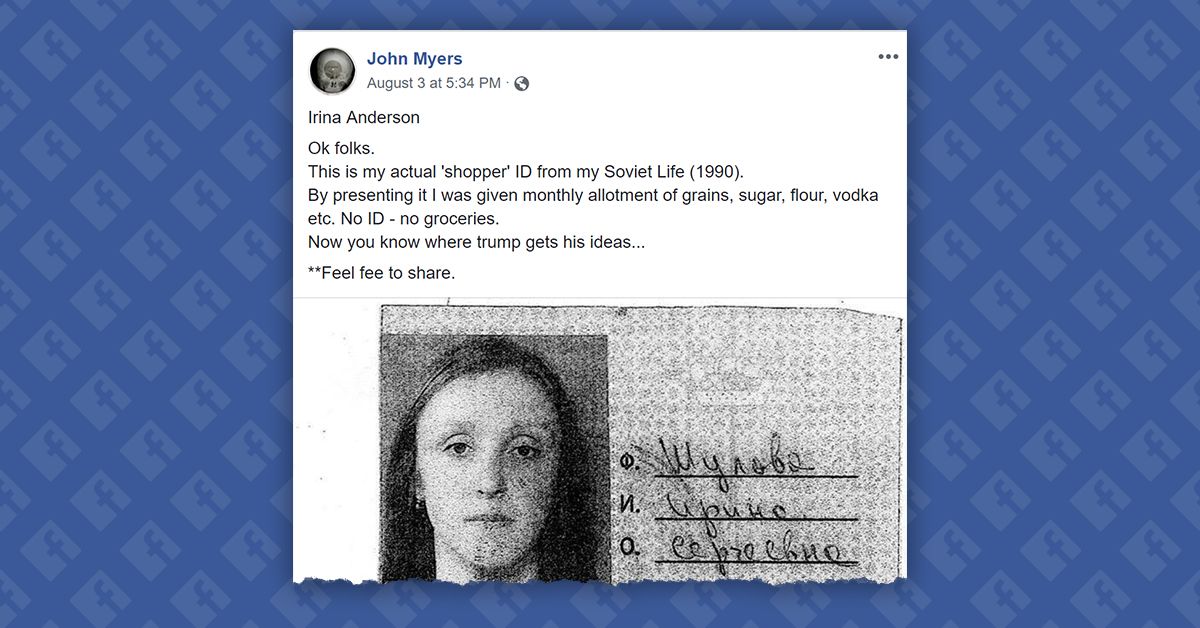

Other critics took a more conspiratorial route, suggesting that Trump had heard about grocery store ID requirements by way of Soviet-era Russia:

We have no reason to doubt the image of the “shopper ID” presented in viral posts like the one displayed above, as a Google Image search for “карточка покупателя” or “Buyer’s Card” yields pictures of countless similar documents. It is useful, however, to understand what exactly these documents were, when they were used, and why they were issued.

Food shortages plagued the Soviet Union sporadically throughout its history, and these cards were issued in some cities towards the tail end of that country's existence following economic reforms enacted in 1989. Those reforms, which were part of an effort to liberalize the Soviet economy in preparation for a transition to a more free-market economy, included devaluing currency (to bring local food prices in line with international values) and ending the government’s monopoly on foreign trade.

A food crisis followed these reforms, in part, because they made it highly profitable for Soviet citizens to sell or hoard goods outside the confines of the government’s official economy, which resulted in a breakdown of food distribution. One briefly attempted solution to this problem, conceived by the local Moscow city government in 1990, was to prevent non-Moscow residents from purchasing goods in Moscow through the issuance of photo IDs, as Marc Garcelon wrote in Revolutionary Passage: From Soviet to Post-Soviet Russia, 1985-2000:

For most of 1990, shoppers were required to present either a passport or a "buyer's card" issued by the Mossovet [Moscow’s local government] when purchasing items in city-operated stores. This last measure proved particularly ill-conceived, as it caused widespread resentment among residents of surrounding counties accustomed to coming to Moscow in search of goods that could not be found in provincial stores.

The buyer’s card shown in the Facebook post above appears to be from the city of Leningrad (Ленинград), which also experienced a major food shortage in November 1990. In Leningrad the presentation of these ID cards was required, along with coupons limiting the amount of food one could purchase each month, when shopping for groceries. As reported by the Los Angeles Times, the coupons were used for rationing basic foodstuffs and limited consumers to "Three pounds of beef, two pounds of sausage, 10 eggs, a pound of flour, two pounds of cereal, half a pound of oil and a pound of butter per person each month."

According to a contemporaneous Chicago Tribune report, local officials worried over how easy it would be to counterfeit these residency cards. “Some council members fear rationing will only feed the black market for food-and for food coupons in a city where a forged residency permit can be purchased for no more than $50,” the paper reported.

In both cities’ cases, the use of these cards was a temporary and unpopular measure that occurred during the tumultuous collapse of the Soviet Union and were the result of fears about food shortages. Their relevance to current United States politics, therefore, is limited. We cannot speak to the claim that this geopolitical history is what inspired President Trump’s impression that Americans need photo ID to shop at grocery stores in the United States, but it seems more likely that he was referring to the occasional need to show ID when paying by credit card or check.