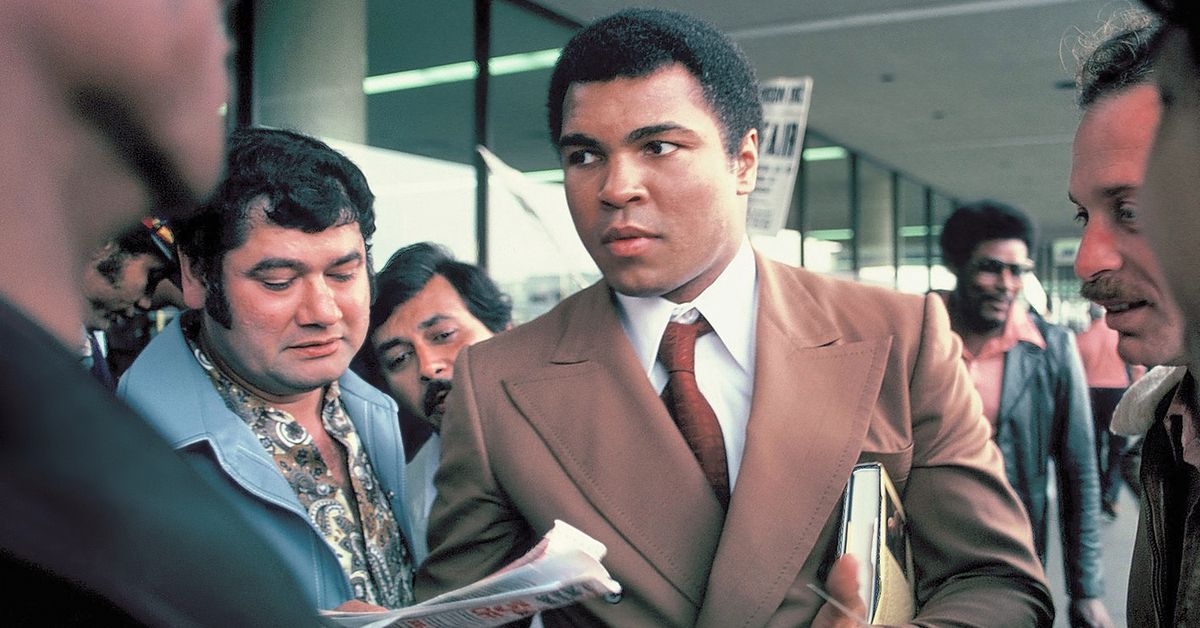

On 8 June 2018, President Donald Trump floated the idea of issuing a pardon to the late boxing legend Muhammad Ali:

I'm thinking about somebody that you all know very well, and he went through a lot, and he wasn't very popular then ... certainly his memory is popular now, I'm thinking about Muhammad Ali. I'm thinking about that very seriously.

But does Ali need a posthumous pardon? The events that led up to his arrest and losing his title started with his refusing the draft on the grounds that as a black Muslim, he was a conscientious objector and thus would not enter the United States military.

Muhammad Ali Refuses Army Induction

Cassius Clay, who changed his name to Muhammad Ali in 1964 after converting to Islam, refused to be drafted into the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War, maintaining that he was a conscientious objector and famously proclaiming that he "ain't got no quarrel with them Viet Cong."

Ali, who was opposed to America's involvement in the Vietnam War and argued that he couldn't serve due to his religious beliefs, was present for his scheduled induction into the Army in 1966, but he refused to step forward each time his name was called:

“My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America,” he said at the time. “And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father. … Shoot them for what? How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.”

A little more than a year later, on April 28, 1967, Ali, then 25 years old, appeared in Houston for his scheduled induction into the U.S. military. He repeatedly refused to step forward when his name was called—despite being warned by an officer that he was committing a felony offense that was punishable by five years in prison and a fine of $10,000. His refusal led to Ali’s arrest and eventual conviction—though he stayed out of prison while his case was appealed. His license to box was suspended in New York the same day, and his title stripped; other boxing commissions followed. Ali was unable to obtain a boxing license in the U.S. for the next three years.

Ali was stripped of his championship title and denied boxing licenses, and a few months later he was found guilty on draft evasion charges.

Supreme Court Overturns Conviction

Ali was fined $10,000 and sentenced to five years in prison but managed to avoid jail time as his lawyers appealed his case. On 28 June 1971, the Supreme Court overturned his conviction with an 8-0 vote, as the New York Times reported at the time:

Muhammad Ali was cleared by the Supreme Court today of the charge of refusing induction into the army. Four years after he was convicted by a jury in Houston, sentenced to five years in prison and then stripped of his heavyweight championship by boxing commissions, the Court declared that Ali was improperly drafted in the first place. The vote was 8-0, with Justice Thurgood Marshall abstaining.

In an unsigned opinion, the court said that the Justice Department had misled Selective Service authorities by advising them that Ali's claim as a conscientious objector was neither sincere nor based on religious tenets.

The Atlantic added more detail to that event in a 2006 article:

When Ali appealed his case to the U.S. Supreme Court for the final time in 1971, liberal stalwart Justice William Brennan convinced his colleagues to hear the case. Justice Thurgood Marshall recused himself because he had been solicitor general when Ali was prosecuted. That left eight justices, who on a first vote sided with the Justice Department in a 5-3 decision.

Ali claimed he qualified for conscientious-objector status because he opposed the war as a black Muslim. The Justice Department challenged that status, citing his statements that he would fight the Vietcong in a “holy war” if they fought Muslims. The justices began drafting their opinions when one of Justice John Marshall Harlan II’s clerks convinced him to take home Elijah Muhammad’s Message to the Blackman in America. Harlan returned to the Court the next day and, convinced of Ali’s sincerity after reading the text, switched sides.

Harlan’s move raised the prospect of a 4-4 split, which would preserve Ali’s conviction and send him to jail without explaining why. The justices instead chose to resolve it on narrow technical grounds and unanimously vacated the conviction.

Does Muhammad Ali Need a Pardon?

Muhammad Ali was found guilty of draft evasion in 1967, but his conviction was overturned by the Supreme Court four years later. So does the boxing legend need a pardon? After Trump floated the idea of pardoning Ali, the boxer's lawyers responded that a pardon was not necessary:

“We appreciate President Trump’s sentiment, but a pardon is unnecessary. The U.S. Supreme Court overturned the conviction of Muhammad Ali in a unanimous decision in 1971. There is no conviction from which a pardon is needed,” said Ron Tweel, a lawyer for the boxer’s estate and his widow, Lonnie.

In addition to the fact that Ali's conviction was eventually overturned, President Jimmy Carter issued a blanket pardon for draft evaders in 1977. This act of clemency did not affect Ali, however, as he his conviction had already been overturned.