In 1653, the Dutch leaders of New Amsterdam (the site of present-day New York City) built a high wall along what was then the city's northern border (now the location of Wall Street) to defend against military attacks by the English, who nevertheless successfully invaded New Amsterdam by sea.

New Amsterdam's wall was intended to repel armed invaders, not immigrants, so it didn't serve a purpose directly analogous to Trump's border wall; nor did the wall fail to achieve its stated purpose, in that it was only intended to stop an invasion by land.

In early January 2019, as the battle between President Donald Trump and congressional Democrats over funding for Trump's promised border wall dragged on, social media users weighed in with arguments for and against erecting a physical barrier along the U.S.-Mexico border.

One of the more interesting claims to emerge from these debates was that a protective wall built by Dutch settlers on the northern border of 17th-century New Amsterdam (now New York City) failed to accomplish its stated purpose -- that is, stopping outsiders from invading the city. In 1664, New Amsterdam was overtaken by the British, who eventually demolished the wall and replaced it with a street (aptly named Wall Street).

The specifics of the claims varied from post to post. A 29 December entry shared on the subreddit r/nyc said the wall was built "To keep the Indians out."

Another version claimed the wall was built to keep the British out:

Do you know why they call it Wall Street in NYC? Because the Dutch literally built a wall to keep the British out of Dutch colonies. You want to know how well walls work? It isn't called New Amsterdam anymore.https://t.co/VnztJ2jxHU

— Ocular Nervosa (@ocularnervosa) January 5, 2019

And yet another said the wall was built in the 1640s and was meant to keep the "bad hombres" out (an apparent reference to Trump's characterization of undocumented immigrants):

In the 1640's the Dutch inhabitants of New Amsterdam built a 12' wall to keep the bad hombres out.

In 1664 the British ignored the wall and took New Amsterdam by sea.

It's now called New York.

They took down the wall and built a street.

It's called Wall Street. pic.twitter.com/Cbhp9N8BDW

— Joe Delmonaco (@JoeDelmonaco) January 7, 2019

Although the broad outlines of the story were accurate, the devil (as always) was in the details.

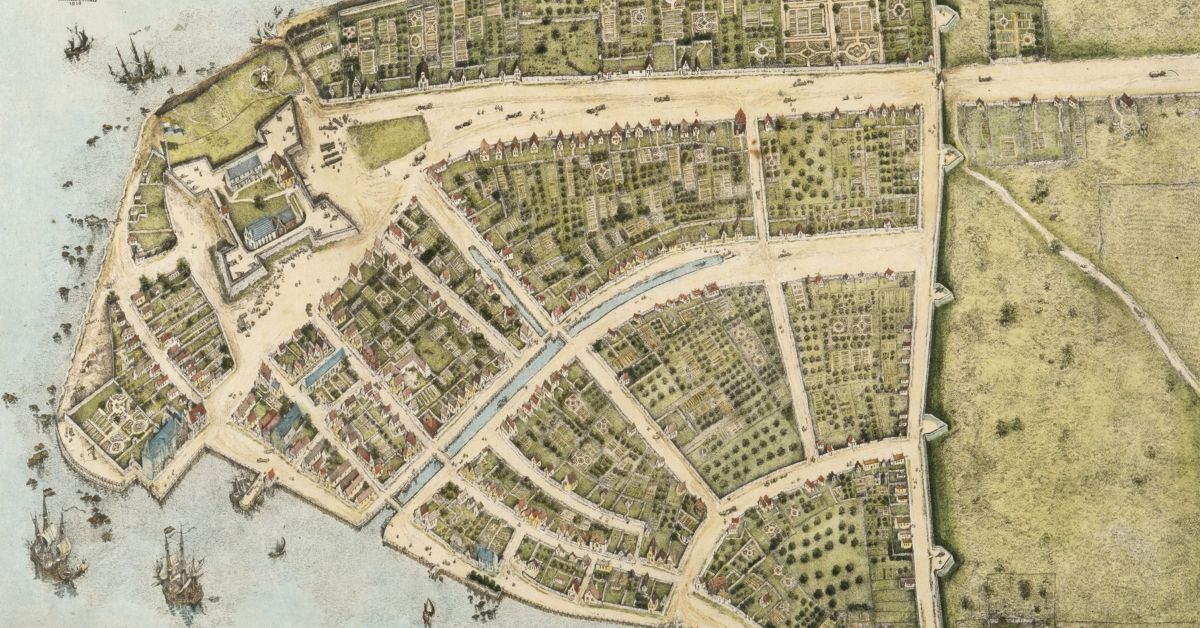

The wall was built neither in 1625 nor in the 1640s, but in 1653, the year New Amsterdam, a Dutch settlement comprising the southern tip of Manhattan Island, was formally chartered as a city. The Dutch Republic was at war with England at the time. The stated purpose of the wall was to prevent the English (not Native Americans) from invading by land.

According to city records, news reached New Amsterdam's leadership in March 1653 that British troops were amassing in New England ("for either defense or attack, which is unknown to us"). They resolved to "surround the greater part of the City with a high stockade and a small breastwork" to defend against a possible land invasion. Thus began the planning and construction of the wall, which would consist of palisades of 9-foot-tall (not 12-foot-tall) wooden planks extending east to west across the breadth of the island. It was completed in four months.

One of the best short histories of the New Amsterdam wall is a five-part essay by Michael Lorenzini of the New York City Municipal Archives, based on original records from the period. One thing he points out is that the wall was only one component of a system of defenses that included ditches in front of the wall, cannon emplacements on the river banks, and Fort Amsterdam at the southernmost end of the island, from which the Dutch could fire upon approaching ships.

Although the First Anglo-Dutch War (1652-1654) ended without the wall's being put to the test, it did play a part in the city's defense when Native American tribes attacked New Amsterdam in 1655, leaving a section of it damaged by fire. "The wall was rebuilt and enforced," Lorenzini told us via email, "and practically every year there was a huge public works project to improve it, including in 1664 when they received word that English ships were on the way."

Despite the end of official hostilities 10 years earlier, the English had never given up their designs on New Amsterdam. When in March 1664 King Charles II deeded all the land from Maine to Delaware to his brother, the Duke of York, the city scrambled to reinforce their defenses. A few months later, four British warships sailed into the harbor with the clear intention of taking the city. Not wanting bloodshed, New Amsterdam surrendered. Not a shot was fired.

Is it reasonable to conclude from that outcome (as some critics of Trump's border wall have argued) that "walls don't work"? Arguably, the wall did work, in that the British never attempted to invade New Amsterdam by land.

We put the question to Lorenzini, asking him first if he found the comparison between New Amsterdam's wall and Trump's border wall apt. "In some ways, maybe," he replied, "but I would say it's more akin to the walled cities of Europe than a border wall such as the Great Wall of China or Hadrian's Wall."

One example of a walled city was New Amsterdam's European namesake, Amsterdam, which was surrounded by defensive walls from the Middle Ages through the late 19th century. But the central purpose of all those walls was repelling invaders, not keeping out immigrants. In fact, the Dutch would have regarded stopping the comings and goings of peaceful foreigners as antithetical to their interests.

Lorenzini continued:

New Amsterdam was a port city; the lifeblood was the free flow of ships into and out of the docks along the waterfront. They traded with everyone, including the English, and especially the native Americans. What they were afraid of was English troops from the Connecticut and Massachusetts colonies coming into the city from the north, and, post-1655, raids from native tribes. At various times they were in conflict with the English and the tribes, but they always wanted to resolve differences and continue trading.

The English were able to take the city peacefully because they promised the merchants to respect the traditions of the Dutch and keep what we would now call the multi-cultural flavor. Not to put too fine a point on it, but it might have been a Dutch city, but it was a city filled with various religions and ethnic groups and they liked it that way, unlike the Puritan cities to the north, which strived for homogeneous societies.

So, it was a military border, not a border to provide immigration control. As a military border, it served its purpose -- no one ever attacked the city from the north -- but much like the Maginot Line in France, it provided a false sense of security and was easily bypassed. The Dutch colony of New Netherlands was not just the lower tip of Manhattan. It extended from Albany to Brooklyn and Queens and down to Delaware and a couple-hundred-meter wall was not going to protect the whole colony.

Certainly the wall was thought valuable to the city's defenses by the English, who continued to expand and maintain it (as would the Dutch when they temporarily reclaimed the city in 1673-4) over the next three decades. It wasn't until 1699, when New York City had essentially outgrown the wall (and the wall had outlived its purpose), that city officials finally petitioned for its demolition, calling for the stones recovered from the battlements that then stood at intervals along the palisades to be repurposed to build a new City Hall.

To clear up one last misconception, it is not the case that the street now known as Wall Street only came into existence after the wall was torn down. Known to the Dutch as the Cingel, the street was ready in use when the British assumed control of New Amsterdam in 1664. As they did with the city itself, they simply claimed it as their own and renamed it.