Pork has a long history of being maligned as an unhealthy and unclean meat primarily due to beliefs expressed in ancient religious texts, while in the modern era some armchair scientists have attempted to provide scientific explanations for the same belief.

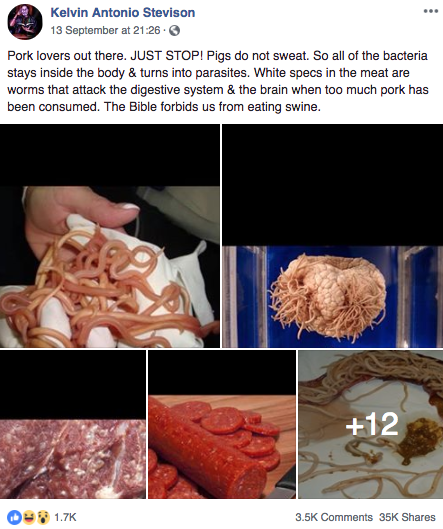

In the latter category, several posts that have gained widespread attention online have claimed that pigs are more likely to harbor dangerous bacteria and parasites because they do not sweat:

This concept was further fleshed out in a longer and well-shared post titled “Why does Islam forbid pork when the pig is one of the creations of God," which asserted that "Unlike other mammals, a pig does not sweat or perspire. Perspiration is a means by which toxins are removed from the body. Since a pig does not sweat, the toxins remain within its body and in the meat."

Our post is not concerned with the epistemological questions posed by any religious text that forbids the eating of pork, but instead with specifically addressing the unfounded claim that pigs are unhealthy to eat because their inability to sweat precludes them from getting rid of toxins or parasites.

Do Pigs Sweat?

It is accurate to say that pigs do not sweat. Although pigs possess some sweat glands, they do not respond to thermoregulatory cues (which is one reason why pigs wallow about in mud to cool themselves). A pig’s lack of functional sweat glands might be a compelling argument about pork's being an unsafe food if the same thing were not also true of other animals which we eat as well.

Most meat we consume comes from animals that do not sweat much or at all, which would call into question essentially all the meat humans eat if sweating were an important factor in food safety. Cows have a limited number of functional sweat glands. Chickens are not mammals and therefore do not possess any sweat glands at all. Humans, with between two to five million sweat glands, are prodigious sweaters compared to most other mammals, especially the ones we commonly eat.

Would Sweating Actually Remove Harmful Chemicals from a Pig’s Body?

A popular folk-medicine notion is that the human body purges itself of toxic substances by sweating them out. Although several chemicals, some of which could accurately be described as toxins, can be found in human sweat, no scientific study has indicated that this could be or is likely to be a significant mechanism for the excretion of dangerous substances:

The body does appear to sweat out toxic materials -- heavy metals and bisphenol A (BPA), a chemical found in plastics, for instance, have been detected in sweat. But there’s no evidence that sweating out such toxins improves health ... The concentration of metals detected in sweat are extremely low. Sweat is 99 percent water. The liver and kidneys remove far more toxins than sweat glands.

Pigs, for the record, also have a liver and a kidney, both of which serve to remove “toxins” from their body. The amount of metals or other toxins that would theoretically be removed from a pig by sweating are negligible, and therefore a pig’s lack of sweat is entirely unrelated to its potential “toxin” load.

Would Sweating Actually Remove Parasites from a Pig’s Body?

Ignoring entirely the scientifically impossible proposal that bacteria, through the process of being jailed in the body of a sweatless animal, could “turn into parasites,” the notion that sweating could be an effective mechanism for the removal of parasites from an animal’s body at all is far-fetched on its own.

The assertion that “worms which attack the digestive system” could escape from a sweat gland requires two absurdities to be true: 1) that a physical, tunnel-like connection exists between a mammal’s digestive system and its sweat glands, and 2) that worm parasites could fit into a sweat gland.

Ascaris suum is a species of roundworm commonly found in a pig’s gastrointestinal tracts. Its life cycle, broadly representative of (though slightly more convoluted than) many of the common species of parasites found in pigs, does not at any point involve the epidermis of the animal:

When [Ascaris suum] eggs are ingested, the larvae hatch in the intestine, penetrate the wall, and enter the portal circulation. After a short period in the liver, they are carried by the circulation to the lungs, where they pass through the capillaries into the alveolar spaces [in the lungs]. Approximately 9–10 days after ingestion, the larvae pass up the bronchial tree, are swallowed, and return to the small intestine by ~10–15 days after infection, where they mature into adult worms.

Those adult worms, with a diameter of around 2-4 millimeters, would be roughly 10,000 times wider than a (human) sweat gland, which are roughly 30-50 µm wide. All livestock, regardless of species, are susceptible to similar parasites, including cows.

Pork, like any other food, is subject to the risk of infection by parasites or bacteria, and could in theory contain heavy metals introduced by the environment in which the animal was raised. Sanitary farming conditions, proper feeding, and prudent food preparation, not sweat glands, are the means of reducing those risks.