As if to remind us that the extreme politicization of public health issues is not unique to the 21st century, excerpts from a 170-year-old editorial in the London Times railing against being "bullied into health" by an "autocratic" government agency found an enthusiastic new audience on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This viral quote comprises a few sentences culled from a lengthy opinion piece in the Aug. 1, 1854, edition of the Times discussing the Public Health Act of 1848 and public sanitation reforms enacted by Edwin Chadwick, a commissioner of the General Board of Health, in the wake of a major cholera epidemic:

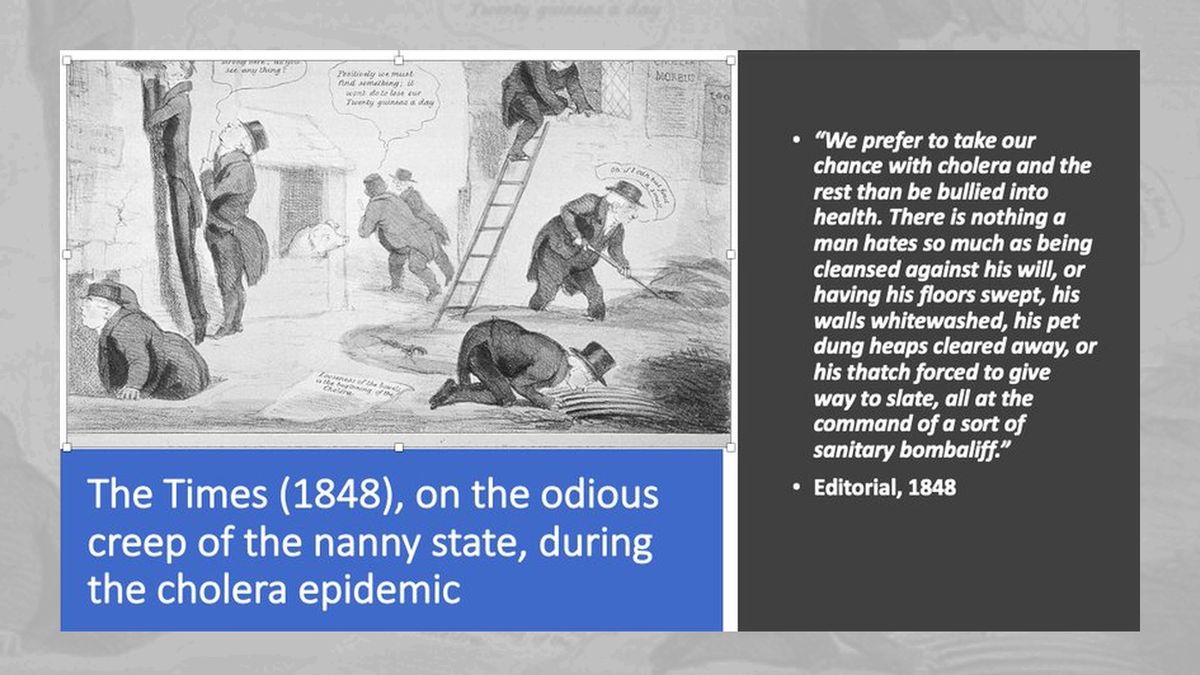

We prefer to take our chance with cholera and the rest than be bullied into health. There is nothing a man hates so much as being cleansed against his will, or having his floors swept, his walls whitewashed, his pet dung heaps cleared away, or his thatch forced to give way to slate, all at the command of a sort of sanitary bombailiff.

As the excerpt suggests, the Times was not a fan of the Public Health Act, public sanitation reforms, or Chadwick. Its editors took the position that the central government had no business "bullying" the public into health (note that the word "bombailiff," or "bumbailiff," was a derisive term for someone who hunts down and arrests debtors).

Here is a longer excerpt from that 1854 editorial, which celebrates the dissolution and reconstitution of the Board of Health (Chadwick was to be replaced):

If there is such a thing as a political certainty among us, it is that nothing autocratic can exist in this country. The British nature abhors absolute power, whether in the form of a Sovereign, a Bishop, a Convocation, a Chamber, a Board, or even a Parliament. The Board of Health has fallen. After an irregular growth of six years, varying between too forward developments and sudden checks, it has finally withered like an exotic unsuited to this soil or clime. We all of us claim the privilege of changing our doctors, throwing away their medicine when we are sick of it, or doing without them altogether whenever we feel tolerably well. The nation, which is but the aggregate of us all, is as little disposed to endure a medical tyrant. Esculapius and Chiron, in the form of Mr. Chadwick and Dr. Southwood Smith, have been deposed, and we prefer to take our chance of cholera and the rest than be bullied into health. Lord Seymour has liberated us from this new and strange dominion. He is the William Tell who has overthrown the sanitary Gesler. The operation consisted in a forcible and humorous history of the Board. Its office was twofold -- to introduce sanitary measures and to carry out the Public Health Act. In its execution of the latter difficult and delicate trust the ruling genius, unfortunately, was too plain. Every where inspectors who should have done their "spiritings" as gently as possible were arbitrary, insulting, and expensive. They entered houses and manufactories just as an improving English landlord might enter an Irish cottage, and insisted on changes revolting to the habits or the pride of the masters and occupants. There is nothing a man so much hates as being cleaned against his will, or having his floors swept, his walls whitewashed, his pet dungheaps cleared away, or his thatch forced to give way for slate, all at the command of a sort of sanitary bombailiff.

Chadwick had been the author of a massive, self-funded study published in 1842 called "Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain. According to a profile of Chadwick on the website of The Health Foundation, a private U.K. health reform organization, he had pushed for nationwide sanitary infrastructure updates:

Chadwick found that there was a link between poor living standards and the spread and growth of disease. A key proponent of sanitary reform, he recommended that the government should intervene by providing clean water, improving drainage systems, and enabling local councils to clear away refuse from homes and streets.

To persuade the government to act, Chadwick argued that the poor conditions endured by impoverished and ailing labourers were preventing them from working efficiently.

The article cites the Times editorial as evidence of the public's "antipathy to high levels of intervention in public health matters." Moreover, "Chadwick's challenging personality and strong support of centralised administration and government intervention made him many enemies in Parliament."

There was also a general consensus that the Public Health Act and Board of Health had largely failed in their mission to effect positive change, though not everyone agreed that it was because the plan relied too much on centralized power. According to today's U.K. Parliament website, its main limitation was that it wasn't centralized enough:

The Act established a Central Board of Health, but this had limited powers and no money. Those boroughs that had already formed a Corporation, such as Sunderland, were to assume responsibility for drainage, water supplies, removal of nuisances and paving. Loans could be made for public health infrastructure which were paid back from the rates. Where the death rate was above 23 per 1000, local Boards of Health had to be set up.

The main limitation of the Act was that it provided a framework that could be used by local authorities, but did not compel action.

With the subsequent passage of the Public Health Act of 1875, Parliament sought to correct the faults of the earlier legislation, in part by making local councils responsible for health and sanitation.