As political rhetoric about the dangers of immigration grew to a “Full Trumpism” fever pitch in the run-up to the 2018 U.S. midterm elections, several online meme-makers and anti-immigration pundits ratcheted up speculation about the potential health risks posed by immigration across the southern U.S. border.

Such claims were usually heavily speculative “what if” statements, tended to be light on factual analysis or good-faith arguments, and were usually attached to misleading or unrelated photos in an effort to generate fear.

"What about diseases?” Brian Kilmeade opined in a 29 October 2018 “Fox & Friends” segment about a Central American caravan, “I mean, there’s a reason you can’t bring a kid to school unless he’s inoculated." Kilmeade did not provide any factual evidence to suggest an increased risk of disease from caravan members, nor did he indicate what kind of diseases were of concern.

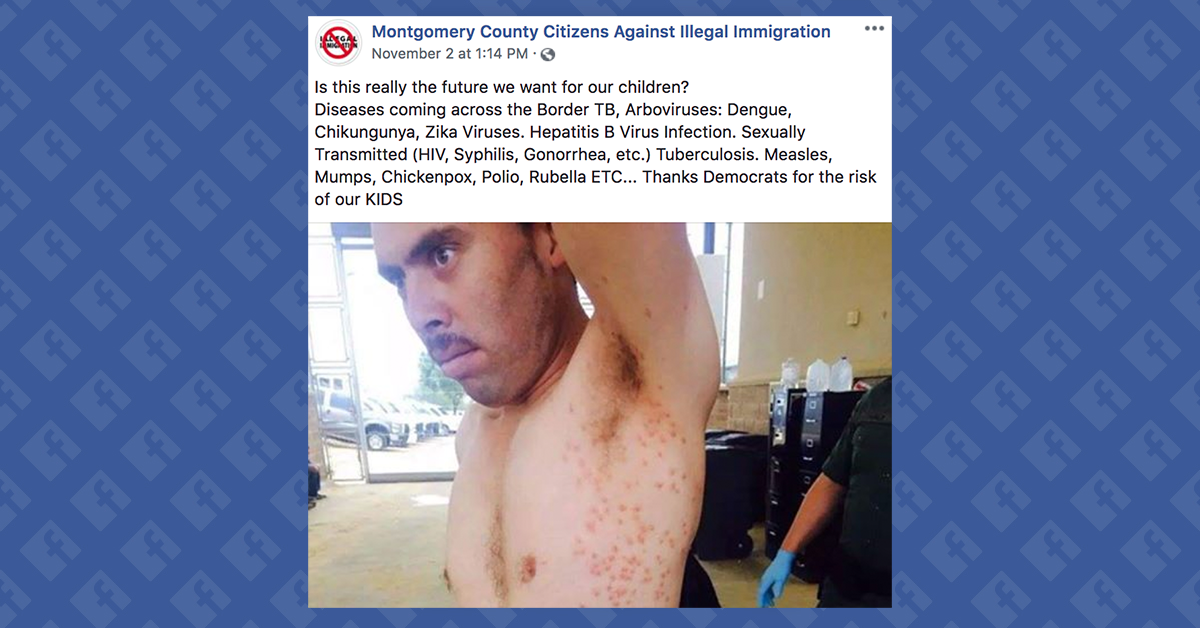

Pictures of Immigrants with Scabies

Nearly all arguments or memes asserting a risk of disease from southern border crossing used photographs and news stories from a specific outbreak that occurred in that area during in the summer of 2014. A representative post of this ilk displayed a photograph and posited that "the bumps on this illegal's body who was detained from the Caravan @ the Border is smallpox":

<!--

-->

The accompanying image showed a man with a case of scabies (a dermatologic condition caused by mites), not smallpox, however.

The photograph used in this 2 November 2018 meme was taken by U.S. Rep. Henry Cuellar at a Customs and Border Protection facility in South Texas and was first published by the Houston Chronicle on 11 June 2014. That year saw the beginning of a large influx of Central Americans attempting to cross into the United States, an event attributed largely to increasing political unrest and poverty in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, and one which overwhelmed the existing U.S. immigration and border patrol capacities at the time.

The 2014 scabies outbreak was heavily reported on by right-wing outlets such as Breitbart and the Washington Times. These outlets and many others uncritically repeated speculative fears presented in local news segments, and they continued to be cited to justify fears of disease from immigrants in 2018. It is therefore informative to look at the fears raised in these 2014 stories to see if they were justified.

A 10 June 2014 article in the Washington Times raised concerns that diseases “of an even more serious nature” than scabies could infect the United States (emphasis on speculative language ours):

Border patrol agents who have already experienced scabies infestations from illegal border crossers now fear the thousands of children who are sweeping into the United States are bringing a host of new diseases and ailments — of even more serious nature.

“We are starting to see chicken pox, MRSA staph infections; we are starting to see different viruses,” said Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol agent Chris Cabrera said, ABC 15 reported ... Mr. Cabrera warned that diseases brought across the border could easily spread to other parts of the country. “It’s contagious. We are transporting people to different parts of the state and different parts of the country,” he said, ABC15 reported.

Breitbart’s coverage from 27 May 2014 raised similar fears about a spread of disease to American children, going so far as to cite a “human stash house” mechanism from a local news segment (emphasis on speculative language ours):

Overcrowding has made it difficult to identify and quarantine infected detainees. Many are concerned that scabies and other illnesses may be passed onto the general public. Hidalgo County Health Department director Eddie Olivarez told Action 4 News that many illegal immigrants are likely contracting scabies in human stash houses, as they make their journey into the U.S. “The situation is that probably in the stash houses on the Mexican side or even on the U.S. side those stash houses are probably infected with this particular illness,” he said.

Each of these reports made a testable prediction: cases of scabies, chicken pox, MRSA, or staph infections brought to America by the surge of immigrants from Central America that began in 2014 would spread to American children in an epidemiologically significant way. The Center for Immigration Studies suggested that the scabies outbreak specifically could present “a health crisis of significant proportion.”

Since the publication of those stories in 2014, no large-scale outbreaks of scabies, chicken pox, MRSA, or staph infections credibly attributable to the transfer of disease from immigrants to the surrounding community have occurred. In the case of the scabies outbreak along the border in 2014, cases of non-detainees contracting the disease appear to have been limited to a few agents, as reported by the National Review:

Approximately 40 immigrants in detention at one center in the U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s San Diego Sector have active cases of scabies, a source tells National Review Online. … Two agents at the Brown Field Border Patrol Station developed rashes on July 3 after processing illegal immigrants from Texas, according to a letter obtained by NRO written by Ron Zermeno, health and safety director of National Border Patrol Council Local 1613.

Scabies, a treatable skin infection caused by microscopic mites, remains a significant risk for detained populations living in close quarters, or for populations of people in developing countries with poorer sanitation facilities, but it is not considered at significant risk for the American populace and is easily treatable with proper medical care.

Do Refugees Present a Significant Health Risk to the Communities They Enter?

The broader question of how refugee populations affect the overall health of the communities they enter is one that merits investigation. The viral Facebook post referenced above makes mention of several diseases, but many of those diseases are commonly present primarily in refugee populations.

A 2017 literature review of infectious disease in refugee and asylum seekers in Europe found that the most common maladies for these populations were tuberculosis and hepatitis B. That same study noted, however, that “though we see high transmission in the refugee populations, there is very little risk of spread to the autochthonous population.” In other words, these diseases spread fast amongst the refugee populations, but not among the communities they enter.

A 2017 report for the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute authored by medical geographer Eric Carter made this point in broader detail. That report stated that the number of Americans or other foreigners who travel to the countries from which refugees are fleeing far exceeds the number of people entering the country as refugees. Therefore, the number of people exposed to foreign disease from Americans returning from refugee countries likely exceeds those exposed to disease from actual refugees:

Tightening border controls usually does little to stem the spread of infectious diseases, partly as a result of the inherent dynamics of how epidemics unfold across space and time. Moreover, the sheer volume of people traveling internationally overwhelms attempts to single out immigrants or foreign nationals for heightened scrutiny at airports and other ports of entry.

As an example, that report cited concerns that immigrants from Central American countries were bringing Zika (one of the diseases attributed to immigrants in the 2018 immigration memes) to the United States in 2015. While pundits attempted to blame illegal immigration for Zika cases in the United States, the numbers do not support such a conclusion:

Even as some politicians and pundits suggest that immigrants are greater carriers of disease, there is no evidence to suggest that their rates of infectious disease exceed those of travelers generally. And migrants make up a small proportion of international travelers. For example, the annual number of U.S. travelers to areas where Zika transmission occurs — about 40 million, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) — dwarfs the number of migrants from those regions ... It appears thus far that the vast majority of Zika cases in the continental United States come from American travelers who acquired the infection while abroad, not from immigrants to the country.

In 2016, 185 million legal northbound crossings took place at ports of entry along the 2,000-mile border between the United States and Mexico. By comparison, the number of migrants in the latest caravan (2018) is in the thousands.

Another relevant point is that many of the maladies listed in anti-immigration memes concern diseases that are all but eradicated in the United States thanks to vaccination efforts. Polio, for example, has been considered eradicated from the entire American continent since 1994.

In fact, many of the countries in Central America from which the migrants are attempting to flee have higher vaccination rates for diseases such as measles than the United States does. In 2017, 92% of children aged 12-23 months were vaccinated for measles in the United States. In Mexico and Honduras that figure was higher, at 96% and 97% respectively. El Salvador and Guatemala have seen a recent decline in vaccination rates, with 85% and 86% coverage in 2017. Regardless, the notion that these commonly vaccinated conditions are in wide circulation outside of the United States and therefore present in higher levels in border-crossing immigrants is dubious.

A measles outbreak in an Arizona immigration detention facility occurred in 2016, infecting both staff and detainees, but it did not spread to the general public. Its peril to the U.S. staff stemmed primarily from a lack of vaccination on the part of the staff working there. Rush Limbaugh attempted to blame a different measles outbreak at Disneyland in 2015 on illegal immigration, but that outbreak was exacerbated not by illegal immigration but by lower than average vaccination rates in Southern California.

While the CDC does suggest some risk of communicable disease transmission across the southern border, they do not attribute it to illegal immigration, but rather to the high level of transportation across the border in general:

The large movement of people across the United States and Mexico border has led to an increase in health issues, particularly infectious diseases such as tuberculosis. Besides the millions of travelers who cross the U.S.-Mexico border each year, the border region also has a population of approximately 11 million people, many of whom cross the border daily for a variety of reasons. More than 30% of U.S. border families are living at or below poverty level, and they are at risk of foodborne, waterborne, and infectious diseases that, for the most part, can be prevented by vaccines.

In short, while detained populations of people held in close quarters carry a higher risk for the transmission of communicable diseases such as scabies or tuberculosis within that population, no evidence suggests that those populations pose a health risk to the surrounding communities. Efforts on the internet to make that risk appear acute do so by misrepresenting out-of-date figures and by ignoring the epidemiological realities of a world that sees one billion people cross international borders every year.