On June 29, 2023, the Supreme Court "severely limited, if not effectively ended, the use of affirmative action in college admissions," as described by Amy Howe at SCOTUS Blog:

By a vote of 6-3, the justices ruled that the admissions programs used by the University of North Carolina and Harvard College violate the Constitution's equal protection clause, which bars racial discrimination by government entities. [...]

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts explained that college admissions programs can consider race merely to allow an applicant to explain how their race influenced their character in a way that would have a concrete effect on the university. But a student "must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual — not on the basis of race," Roberts wrote. [...]

Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett joined the Roberts opinion.

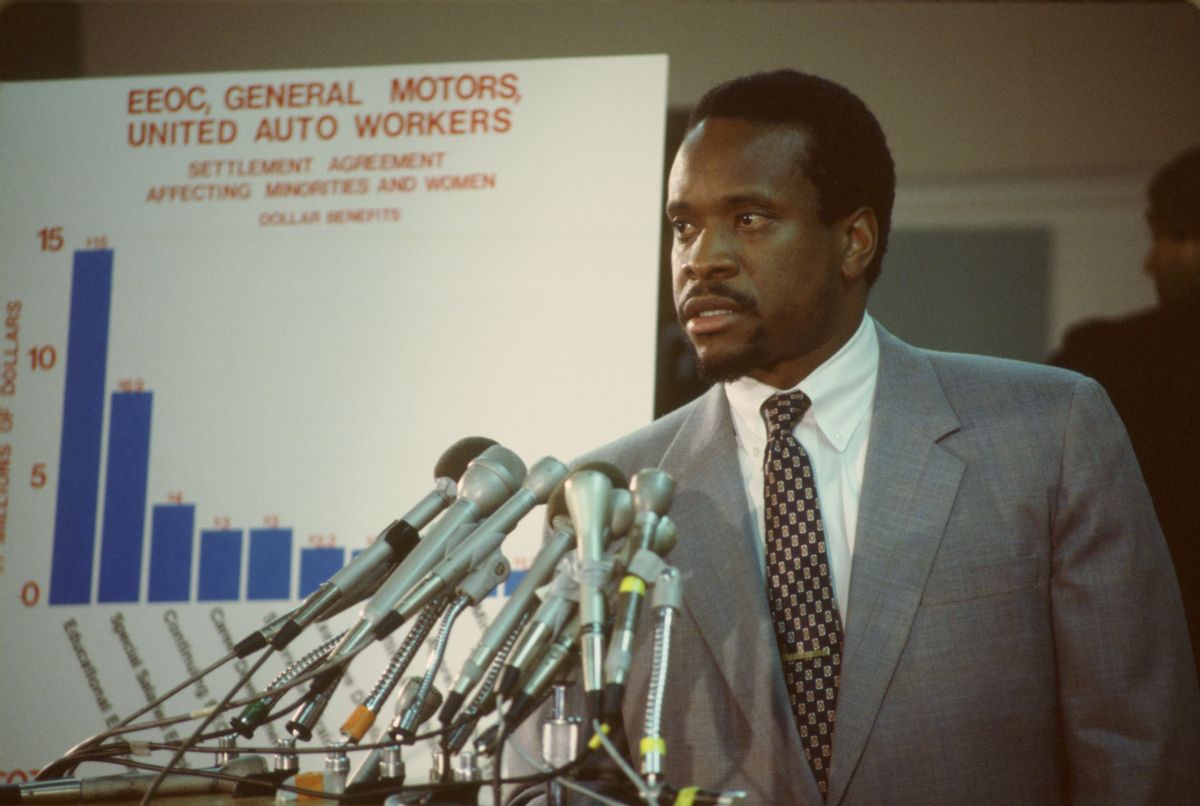

Clarence Thomas' concurrence with the majority opinion led several media outlets to rehash an assertion that, at least for a period of time in the 1980s when he was chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), Thomas's views on affirmative action programs were ambivalent — if not opportunist. This claim has been in recirculation since the Supreme Court announced that they had added cases challenging affirmative action to their docket:

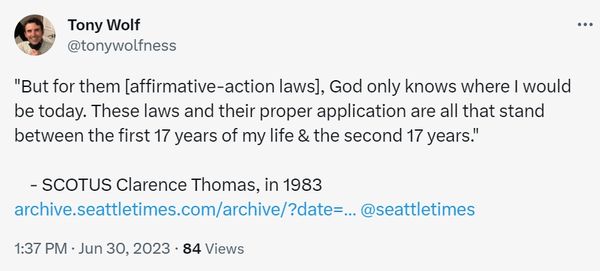

(@tonywolfness/Twitter)

(@tonywolfness/Twitter)

That claim appears to have first been raised following Thomas' nomination to the Supreme Court — in a July 14, 1991 New York Times article titled "On Thomas's Climb, Ambivalence About Issue of Affirmative Action." That article cited a line from a January 1983 speech given by Thomas to employees of the EEOC:

In a 1983 speech to staff members at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which he then headed, he said that affirmative action laws were of "paramount importance" to him.

"But for them, God only knows where I would be today," he said. "These laws and their proper application are all that stand between the first 17 years of my life and the second 17 years."

Though repeated in this way by several media outlets both during Thomas' Supreme Court nomination process in the 1990s and again in 2023, this is an incorrect paraphrase of Thomas's statements. Thomas's full remarks were published as a law article in the Journal of Labor Law in April 1983.

When read with the full context of this speech, it is clear that the "them" used in the phrase "but for them" referred not to affirmative action laws in particular, but to equal employment opportunity laws — as articulated in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — more generally.

The speech, broadly, was a defense of the EEOC's work during the Reagan administration, which faced criticism over a massive reduction in discrimination claims pursued under its leadership.

The Context

Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act — a landmark bill signed during the Lyndon Johnson Administration — prohibits discrimination by employers on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. The EEOC, which first began operations in 1965, was created as part of the 1964 Act as the agency tasked with investigating and enforcing Title VII violations.

Over the years, the EEOC has expanded to investigate and enforce violations of other Federal anti-discrimination laws including those against discrimination against pregnant women, age discrimination, and disability discrimination. By the end of the Carter administration, the EEOC had expanded considerably under chairwoman Eleanor Norton's tenure, as described in a March 1981 report:

Thanks in part to Ms Norton's streamlined methods, which enabled EEOC to process 50,000 cases per year during her tenure, she views the equal-employment field as "very stable now. We have had 10 years of extraordinary and deep court cases to build the law."

"Even if they disbanded EEOC tomorrow," she said, "and there is no way they could, there would still be thousands of court cases presented each year based on precedent."

Norton, here, was referencing an unpublished report commissioned by the Reagan transition team that was extremely critical of the EEOC, as reported by The Washington Post in January 1981:

A Reagan administration advisory panel has urged that equal employment opportunity law and procedures to be changed so that much more evidence would be required to find a business guilty of discrimination and no business could be forced to adopt an "affirmative action" plan against its will.

The advisory unit attacked the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission for having created a new racism in America in which every individual is judged by race."

The group was led by J.A. Parker, a black and head of the Lincoln Institute, a conservative think tank that deals with black issues. Its unpublished report was sent to the then-president-elect last month.

Following Reagan's inauguration, the chairmanship of the EEOC office was vacant until early 1982, when Thomas was tapped to lead the EEOC. Democrats, at the time, were skeptical of Thomas' commitment to alleviating discrimination. These concerns were not helped by a massive decline in cases pursued under Thomas, or by the massive reduction in the EEOC budget under Reagan, as reported in a 1983 article:

In Fiscal Year 1982, there was upwards of 70 percent fewer cases filed in court than in 1981 on behalf of grieved workers. EEOC employees report that, because of a lack of staff and resources, cases often receive perfunctory investigation and in many instances, charges have been dismissed or "no caused" because they would prove too difficult or time-consuming to process.

The speech in question, delivered to employees of the EEOC, was a response to these criticisms and an attempt to clarify to his staff what Thomas felt the role of the EEOC should — and should not — be. In his remarks, Thomas cited "the changing nature of discrimination," and heralded inroads his EEOC had made in fighting age and gender discrimination:

It should not be surprising that many of our most prominent cases involve allegations of age and sex discrimination, many resulting from reductions in force and forced retirement.

This does not mean that charges of race, national origin, or religious discrimination are not filed with the EEOC and that the EEOC does not bring suit in such cases. It only means that there is now a special public and judicial sensitivity to cases involving age and women.

Importantly, the speech is explicitly critical of the discourse surrounding affirmative action, and the policies Thomas advocated represented, at best, a muted skepticism toward the concepts' then-present use:

No one in his right mind seriously questions the legal and moral bankruptcy of discrimination. The same unanimity of opinion does not exist for affirmative action.

Affirmative action has been and will continue to be a subject of hot debate because mere mention of the term divides interest groups into two warring camps: one hotly in favor and one hotly opposed. [...] In their haste to condemn each other, the camps lose sight of the nature and purpose of equal employment opportunity laws. [...]

This divisive debate results in general confusion and misunderstanding about affirmative action which, in turn, tends to undermine the effectiveness and legitimacy of the enforcement of civil rights laws.

As the lead agency in the enforcement of federal equal employment opportunity laws, the EEOC cannot stand by and allow confusion about affirmative action to undermine our enforcement efforts. We must attempt to bring out and clarify the issues obscured by this debate. [...]

Much of the heated debate and public confusion over affirmative action, in fact, stems from the confusion between flexible goals and inflexible quotas, and the use of these two distinct terms interchangeably.

Thomas, in his speech, expressed the view that "too much posturing" had taken place over the debate about affirmative action, but he also affirmed that affirmative action programs had been "critical to minorities and women in this society."

'But for Them, God Only Knows Where I'd Be Today'

The section of the speech paraphrased to claim that Thomas was once amenable to affirmative action followed the above remarks:

It is my view that too much posturing has taken place on issues such as affirmative action, which are critical to minorities and women in this society.

The problems which we face in the area of equal employment opportunity must be solved. For the most part, they must be solved by applying legal principles of paramount importance to me.

But for them, God only knows where I would be today. [...] These laws and their proper application are all that stand between the first 17 years of my life and the second.

The reference to the "first 17 years" of his life is an allusion to statements Thomas made in the opening of this speech, when Thomas referenced "the fact that the Chairman of the EEOC spent 17 years of his life (one-half) under strict segregation." This connection, along with the broader context of the speech, makes it clear that "these laws" are those contained in the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act ended segregation when Thomas was a few months shy of 17. It also created the "equal employment opportunity laws" at issue under Title VII that provide the EEOC — the audience of his speech — with its legal authority. At the end of his speech, during this second allusion to the end of segregation, Thomas warned against the improper use of those laws, even when used with good intention:

I abhor any effort to twist, bend, or distort them [legal principles] for any reasons, whether such distortions are said to help or hurt minorities or women. No one should be permitted to turn these laws on their heads just because they have good intentions. These laws and their proper application are all that stand between the first 17 years of my life and the second.

In sum, Thomas did not present anything more than a muted acknowledgement of the EEOC's role in some forms of affirmative action, and the laws or principles he was referring to in remarks that have since gone viral did not concern affirmative action specifically, but the principles contained within the 1964 Civil Rights Act more broadly.

Criticism

That Thomas, who recently ruled against the use of racial quotas in college admissions, would have described affirmative action as "critical to minorities and women in this society" has been painted as an example of Thomas' hypocrisy on affirmative action.

The portion of the speech often cited to make this point is mischaracterized, even if that point has validity. Specifically, the 1991 reporting in The New York Times reported, as its primary scoop, that Yale Law School had a 10 percent minority goal the year in which Thomas applied to and was accepted into the program:

Judge Clarence Thomas, who came to prominence as a fierce black critic of racial preference programs, was admitted to Yale Law School under an explicit affirmative action plan with the goal of having blacks and other minority members make up about 10 percent of the entering class, university officials said.

Under the program, which was adopted in 1971, the year Judge Thomas applied, blacks and some Hispanic applicants were evaluated differently from whites, the officials said. Nonetheless, they were not admitted unless they met standards devised to predict they could succeed at the highly competitive school. [...]

"We did adopt an affirmative action program and it was pretty clearly stated," said Prof. Abraham S. Goldstein, who was dean of the Law School from 1970 to 1975.

Thomas has also acknowledged this part of his history, as reported in 1980 by The Washington Post. "The worst experience of his life," he reportedly explained at the time, "was attending college and law school with whites who believed he was there only because of racial quotas for the admission of blacks."

Frank Washington, a Yale friend interviewed by Newsweek in 1991, said that Thomas had, in private, "recognized that affirmative action helped to get him into law school, but on the basis of economic deprivation rather than race."

The Bottom Line

While there are separate arguments to be made of the notion that Thomas' views on affirmative action are hypocritical due to his personal benefit from such programs, removing context from a speech to make it sound like that alleged hypocrisy was more overtly stated is misleading.

Because the laws and principles Thomas was referring to were those contained in the 1964 Civil Rights Act and not any specific affirmative action legislation, the claim is False.