While surveillance video showed multiple people watching Kari's attack and not intervening to help her, another person who was not seen in the footage successfully distracted the assailant by yelling, according to Kari's daughter. Also, in the Genovese case, a handful of people — including a woman who held Genovese in her final moments — called police or took other actions to try to stop that killing.

When surveillance footage surfaced in late March 2021 showing a man attacking a 65-year-old Filipino woman on a busy Manhattan street in broad daylight, social media users likened the alleged hate crime to the notorious murder of 28-year-old Kitty Genovese more than a half-century earlier.

As the legend went, on March 13, 1964, "38 respectable, law‐abiding citizens in Queens watched" a knife-wielding man chase and kill Genovese as she walked to her Kew Gardens apartment after a late-night shift managing a bar.

"Not one person telephoned the police during the assault; one witness called after the woman was dead," reported the New York Times at the time.

Flash forward 57 years, and the video depicting witnesses' reactions to the assault near Times Square appeared to meet the definitions of what psychologists dubbed "Genovese syndrome," or "the bystander effect," in light of The New York Times' portrayal of the killing.

"A big man viscously and repeatedly kicked a small Asian woman. He could have killed her. Men inside the building watched it happen," another post read. "I remember Kitty Genovese."

Below, we lay out evidence to debunk the flaws in that logic.

Namely, it's false to say no one who saw the 2021 Manhattan assault did nothing to help Vilma Kari. According to her daughter, a witness who could not be seen or heard in the surveillance footage successfully distracted the attacker so he would leave her mother alone.

Also, numerous investigations over the years have debunked various aspects of the highly popularized, above-mentioned New York Times story about Genovese's death, published on March 27,1964. While no one knows exactly how many bystanders could have feasibly saved her life, criminologists, journalists, and authorities all agree on this: not one person saw the attack in its entirety, and a few people indeed tried to help her.

Witnesses To Kari's Attack Near Times Square

Kari was walking to church on March 29, 2021, when authorities believe a man randomly approached her in front of a luxury apartment building, shouted, "You don't belong here," kicked her to the ground, and repeatedly stomped on her face, per news reports.

Days later, police arrested Brandon Elliot, a 38-year-old parolee convicted of killing his mother nearly two decades prior, on suspicion of the violent hate crime. (The Associated Press reported that his lawyers urged the public to “reserve judgment until all the facts are presented in court," proceedings for which had not started as of this writing.)

Meanwhile, social media users framed the surveillance video from inside the apartment building as evidence of the so-called "bystander effect." That is, the presence of people discourages individuals from intervening to help someone in distress.

Based on our analysis of the footage, it was true that multiple people were recorded watching the attack from inside the apartment's lobby and did not intervene for reasons that were not made clear.

Specifically, at least three witnesses who were identified as workers in the apartment watched glimpses of Kari's assault, looking through glass windows and an open door. About 10 seconds after the attacker fled, one of those workers closed the building's door as Kari remained on the ground.

A longer version of the surveillance video, obtained by multiple media outlets, showed the workers waited in the lobby for more than a minute before going outside and approaching Kari. (Per the workers’ union, SEIU 32BJ, they made that decision to delay their aid because they thought the suspect had a knife, and they wanted to make sure he was gone, according to The Associated Press.)

A police squad car eventually arrived, according to the video's extended cut, and the witnesses and officers were recorded with Kari on the sidewalk for several more minutes.

Medics hospitalized Kari with a fractured pelvis and contusions on her body and forehead, according to news reports.

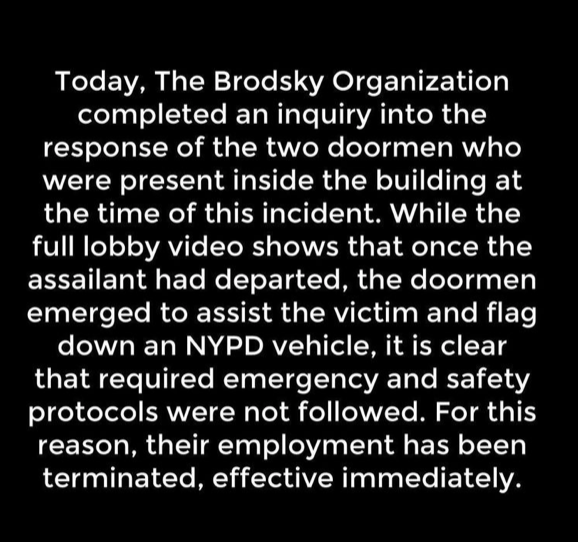

On April 6, the apartment building's management company, the Brodsky Organization, announced via the below-displayed Instagram post that it had fired the two doormen who watched the attack following an investigation into their actions. It was unclear to whom the third bystander reported for work, and whether their response to the assault threatened their employment, as well.

However, those people were not the only people who witnessed the attack.

According to Kari's daughter, Elizabeth Kari, a witness who could not be seen or heard in the footage "yelled and screamed to get the assailant's attention," and seemingly distracted the attacker so he would leave her mother alone. The daughter shared on a GoFundMe page, which the platform confirmed as an authentic posting from her, the following anecdote:

[There] was someone who was standing across the street that witnessed my mom getting attacked who yelled and screamed to get the assailant’s attention. That is where the video cuts off as the attacker crossed the street to him. To this person, I understand your decision in remaining anonymous during this time. I want to THANK YOU for stepping in and doing the right thing.

In sum, considering that testimony from Kari's daughter, it was false to claim that no one who watched Kari get kicked and stomped on outside a Manhattan apartment did anything to try to help her.

Kitty Genovese: The 'Perfect Tabloid Murder'

Among The New York Times' errors in its portrayal of Genovese's death were the number of people who allegedly witnessed her final moments, heard her cries for help, or tried to get emergency aid by calling the police. It also omitted key biographical facts about the victim, including the fact that she was survived by her partner, Mary Zielonko, and that they lived together in the apartment where Genovese died.

"It's like the perfect tabloid murder," Michael Hobbes, of The Huffington Post and the podcast "You're Wrong About, said in the episode about Genovese's killing. "You can put the stuff in the paper that fulfills all of these little narrative chapters."

The facts of her 1964 killing are these, based on court documents, newspaper archives, and scholarly journals:

Around 3 a.m., a man named Winston Moseley randomly spotted Genovese and chased her with a knife as she attempted to walk a few hundred feet from her vehicle to her apartment building. He told prosecutors he stabbed her twice. When someone called out from an open window, he fled temporarily.

We know now that witness was Robert Mozer, a neighbor who later told prosecutors that he heard Genovese's cries for help, and saw her kneeling down with a man bending over her. He yelled: "Let that girl alone!"

Suffering from stabbing wounds, Genovese crawled to the back of the apartment building. (Joseph De May Jr., a lawyer and Kew Gardens resident who thoroughly investigated the crime, believed she was trying to reach a neighborhood bar a few doors away.) Moseley returned to sexually assault and fatally stab her. A 1995 court document citing Moseley's confession to the killing read:

During the commission of this brutal attack, Moseley could hear that he had awakened residents of the apartment building. He heard a door open 'at least twice, maybe three times, but when [he] looked up ..., there was nobody up there.'

That was likely Karl Ross, a friend and neighbor to Genovese whose behavior among all witnesses most closely matched the New York Times' portrayal of the scene. He coined the bystander effect's slogan: "I didn't want to get involved."

Based on evidence, however, fear, not apathy, appeared to drive his decision-making that night, potentially because he was gay and worried that his identity could make him a target. Drunk that night, he indeed cracked his door open and saw Genovese lying in the hallway — still alive and attempting to speak, according to History.com. He shut the door and phoned a friend who discouraged him from getting involved. Minutes later, he climbed out of his apartment's window and walked across the building's roof to a friend's unit, where he called police. The Nation reflected in a 2014 story:

In the story as told by the 'Times,' it’s easy to hear 'I didn’t want to get involved” as 'I didn’t want to help my suffering neighbor.' But the more one learns about Ross, the easier it gets to hear another translation: 'I didn’t want to get involved with the police, who — like The New York Times — view homosexuality as a menace to society.'

At least one other person also claimed to have alerted law enforcement to the attack, according to news reports.

Around the time of Ross' above-mentioned actions, a woman named Sophie Farrar — who lived on the same floor as Genovese and her partner — rushed to Genovese's aid and screamed for someone to call police. "I held her head, and I had blood all over my hands," she later testified in court.

In other words, it was false to claim that no witnesses to Genovese's deadly assault attempted to help her, and that no one called police until after she died. In reality, she took her last breaths en route to the hospital, after medics and law enforcement arrived to the apartment to investigate.

(See De May Jr.'s analysis of court transcripts and other evidence for more detailed explanations of witnesses' testimonies. A prosecutor told him that "only about half a dozen people [...] saw anything that could be used in trial," further discrediting the 1964 reporting by The New York Times).

Police arrested Moseley five days after the attack while investigating an unrelated burglary.

The Cultivation of Bystander Intervention

The year Moseley died in prison, in 2016, Bill Genovese, Kitty's brother, told The Washington Post the family spent decades trying to shield their mother from news stories that framed the violent death as a spectacle for heartless onlookers watching from their apartments or the street.

“It would have made such a difference to my family knowing that Kitty died in the arms of a friend,” he said in a documentary about his investigation into his sister's death, called “The Witness.”

Despite its errors and misconceptions, the widely believed portrayal of Genovese's death, a horrifying scene in which people's diffusion of responsibility prevented them from intervening, took on a life of its own. The narrative inspired the modern-day 911 system, Good Samaritan laws, anti-stalking programs, media projects, literature, and — most relevantly to this report — new research into human behavior.

In the late 1960s, American social psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley set the framework for a new field of research by showing via test studies that witnesses do care about individuals in crises but sometimes do not offer help, pending the number of people experiencing the same thing. Britannica Encyclopedia says in its entry about "bystander intervention," as of this writing:

"The story of Genovese’s murder became a modern parable for the powerful psychological effects of the presence of others. It was an example of how people sometimes fail to react to the needs of others and, more broadly, how behavioral tendencies to act prosocially are greatly influenced by the situation."

Over the years, scientists applied the concept to routine forms of helping, too, and continued to study the evolving psychological theory.

Meanwhile, news outlets including The New York Times published multiple articles addressing its errors and mischaracterizations of Genovese's death. A. M. Rosenthal, a former editor at the newspaper who oversaw the 1964 story, was quoted in one of them, referring to the number of people who heard her attack:

“I can’t swear to god there were 38 people. Some people say there were more, some people say there were less, but what was true is people all over the world were affected by it,” he said. “You bet your eye it did something, and I’m glad it did.”