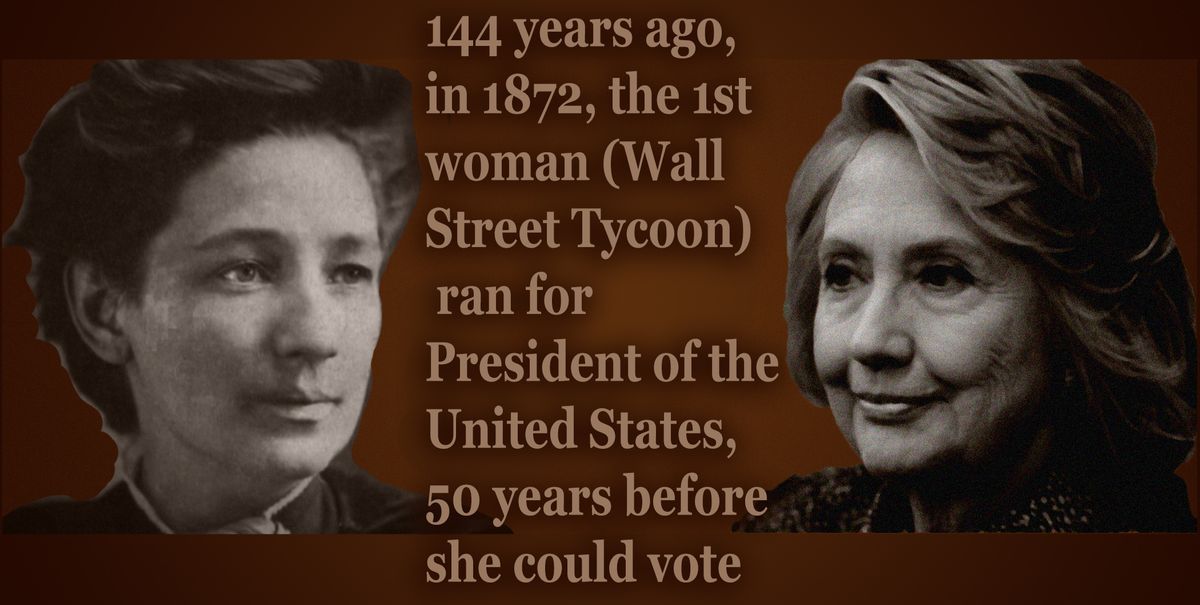

Victoria Woodhull was technically the first female nominee for President in 1872, but no votes for her were recorded or tallied, and she was several months shy of 35 at the time of her campaign and thus technically ineligible to hold office.

While newspapers and online news outlets described Clinton as the first female nominee, Clinton herself repeatedly qualified the statement with "[of a] major party"; Clinton did not declare herself the first female presumptive nominee without that qualifier.

On 6 June 2016, the Associated Press declared Hillary Clinton the presumptive nominee of the Democratic Party on the eve of six of the seven remaining primaries and caucuses. Subsequent headlines described Secretary Clinton as the first female nominee:

Almost as soon as the headlines began to appear declaring Clinton the first female nominee, social media began to dispute the descriptor — apparently, suffragette Victoria Woodhull was entitled to that "first," not Secretary Clinton:

Victoria Woodhull ran as Equal Rights Party nominee for President, 1872: #LOC pic.twitter.com/z1fdZhNSRz

— Michael Beschloss (@BeschlossDC) June 7, 2016

Other memes asserted that not only was Victoria Woodhull the first female nominee, but that a number of other women assumed the role in the years after Woodhull's "first." A Facebook post published the following list of female contenders that came before Clinton and after Woodhull:

From top left: Victoria Woodhull, 1872, Equal Rights Party; Belva Ann Lockwood, 1884 & 1888, National Equal Rights Party; Charlene Mitchell, 1968, CPUSA; Linda Jenness, 1972, SWP; Margaret Wright, 1976, People's Party; Maureen Smith, 1980, Peace & Freedom Party; Deirdre Griswold, 1980, WWP; Sonia Johnson, 1984, Citizens Party; Gavrielle Holmes, 1984, WWP; Lenora Fulani, 1988 & 1992, New Alliance Party; Willa Kenoyer, 1988, SPUSA; Helen Halyard, 1992,SEP; Gloria La Riva, 1992, 2008 & 2016, WWP & PSL; Monica Moorehead, 1996, 2000 & 2016, WWP; Marsha Feinland,1996, Peace & Freedom Party; Mary Cal Hollis, 1996, SPUSA; Cynthia McKinney, 2008, Green Party; Peta Lindsay, 2012, PSL; Jill Stein, 2012 & 2016, Green Party. Frankly, erasing progressive feminists is exactly what Hillary wants.

Edit: Mary Scully is also running as an independent socialist in 2016[.]

The Guardian profiled some of the women depicted in that meme, and their respective bids for the office of President. In April 2015, Politico reported:

Few know, though, the name of the woman who put the first crack in that highest, hardest glass ceiling. That honor belongs to a beautiful, colorful and convention-defying woman named Victoria Woodhull, who ran for the office in 1872, 136 years before Clinton made her first run in 2008. Woodhull, who died nearly twenty years before Clinton was even born, hazarded a path on which no woman before her had ever dared to tread. Even more amazing is that she did it almost 50 years before the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920 gave women the right to vote. On Election Day, November 5, 1872, Victoria Woodhull couldn’t even vote for herself.

Woodhull ran under the banner of the Equal Rights Party—formerly the People’s Party—which supported equal rights for women and women’s suffrage. The party nominated her in May 1872 in New York City to run uphill against incumbent Republican Ulysses S. Grant and Democrat Horace Greeley and selected as her running mate Frederick Douglass, former escaped slave-turned-abolitionist writer and speaker. On paper, it was an impressive pick, but not really: Douglass never appeared at the party’s nominating convention, never agreed to run with Woodhull, never participated in the campaign and actually gave stump speeches for Grant ... that’s just one more of many caveats about Woodhull, who, throughout her long life—she died in England in 1927 at age 88—never much cared for rules or regulations of a game she considered egregiously rigged against women. On inauguration day, she would have been just 34 years old. Article 2, Section 1 of the Constitution requires that the president be 35 on the day “he” takes office. In the end, though, her youth was the most moot of moot points, because Victoria received zero electoral votes. (There’s no record of how many popular votes she received; though we do know that 12 years later, another woman running for president under the banner of the same Equal Rights Party racked up 4,149 votes in six states.)

Woodhull's controversial run was not without consequence:

Two years later, Woodhull was officially nominated to be the presidential candidate for the Equal Rights Party, a political group she helped to organize. Frederick Douglass, the famed civil rights activist, was nominated to be her vice president, though he never acknowledged or accepted the nomination publicly. But while historians look back as Woodhull’s nomination as an historic first, her long-shot candidacy caused her serious trouble as soon as the nominating convention was over, Richman and Freemark report.

“As a result of the notoriety of the nomination, Woodhull was evicted from her home and she had some trouble making ends meet,” [biographer Amanda] Frisken tells [reporters Joe] Richman and [Samara] Freemark. Woodhull's family was forced to sleep in her brokerage office for a period of time, as New York landlords were unwilling to rent to her, Kate Havelin writes in her book, Victoria Woodhull: Fearless Feminist. Woodhull's 11-year-old daughter, Zula, meanwhile, had to leave her school as other parents didn't want Zula to influence their children.

As the national press tore her apart, Woodhull lashed out at allies who she believed let her down. The last straw came when she called out a former friend, Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, who she claimed had had dozens of affairs. When she published these allegations in her newspaper, she was arrested for violating morality laws and spent Election Day in a jail cell. Because she wasn’t on any ballot in the country, there are no records of how many people might have voted for her, Frisken tells Richman and Freemark.

It wasn't a secret that Woodhull ran for president in 1872, half a century before the ratification of the 19th Amendment afforded women the right to vote. But the headlines were not as precise as Clinton herself:

Thanks to you, we have reached a milestone. The first time in our nation's history that a woman will be a major party nominee for president.

Clinton also included the modifier on Twitter:

For the first time in our history, a woman will be a major party’s nominee for President of the United States. pic.twitter.com/4iLojpuPj8

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) June 8, 2016

It is true that Victoria Woodhull ran for office in 1872, long before the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. But it was also true that Clinton is the first presumptive nominee of a "major party," pending the party's July 2016 Democratic National Convention.