An image depicts an object identified as a slave collar on exhibit at a Philadelphia museum of slavery artifacts. However...

The pictured artifact was not made by Tiffany & Co., nor is it on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

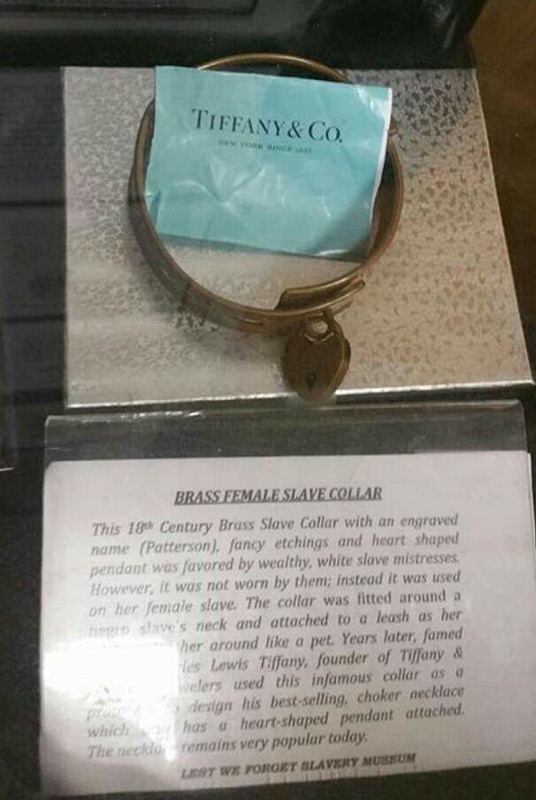

On 26 September 2016, a Facebook user published the following status update and photograph reporting that his sister had captured an image of a Tiffany slave collar at an "African-American history museum in DC" (presumably a reference to the National Museum of African American History and Culture):

My lil sis is at the African-American history museum in DC. Crazy the things u never knew. Still want that Tiffany Bracelett? Just saying.

The photograph had actually appeared on Facebook as early as May 2016 and was not taken by anyone in September 2016. Many social media interpreted the picture to mean that Tiffany & Co. had once manufactured high-end slave collars like the one seen in the museum display, but the text of the exhibit only stated that the design of Tiffany chokers was supposedly inspired by such collars:

This 18th Century Brass Slave Collar with an engraved name (Patterson), fancy etchings and heart shaped pendant was favored by wealthy, white slave mistresses. However, it was not worn by them; instead it was used on her female slave. The collar was fitted around a negro slave's neck and attached to a leash as her [indecipherable] ... her around like a pet. Years later, famed [indecipherable, Charles] Lewis Tiffany, founder of Tiffany & [Co. Jewelers] used this infamous collar as a prototype to design his best-selling, choker necklace which [indecipherable] has a heart-shaped pendant attached. The necklace remains very popular today.

LEST WE FORGET SLAVERY MUSEUM

The text's final line lent a clue as to the image's origin: The Lest We Forget Black Holocaust Museum of Philadelphia (LWFSM), whose Facebook "About" page describes the facility thusly:

The "Lest We Forget" Black Holocaust Slavery Museum offers an opportunity to examine and explore factual aspects of the African Slave Trade experience.

Our artifacts and historical document speak for themselves and truly "bring history alive". The exhibit conveys an awareness of a dark and tragic period in American as well as African history.

We contacted the LWFSM, and curator Gwen Ragsdale confirmed that the exhibit was part of the museum's collection of artifacts from the slave trade. She maintained that the collar was a genuine "slave collar" from the 1700s, most likely a gift given to a slave owner to use decoratively on a female slave. She also noted that, like much of the history of slavery, tracking the precise provenance of the item was difficult due to a dearth of historical records, and much of the information retained about the practice was passed along orally across generations.

The curator told us that photography was not permitted inside the LWFSM in part because it often leads to the spread of misinformation on social media. Indeed, despite the signage, the depicted "brass female slave collar" was not directly linked with Tiffany & Co. or the company's founder in the exhibit's text — the collar was simply referenced as inspiration for the jewelry brand's popular "Tiffany heart."

Determining the exact inspiration for any particular item of Tiffany & Co. jewelry is difficult, as it involves assigning motives and experiences to people who are not here to explain those aspects for themselves. However, the basic history of Tiffany & Co. is well documented given the prominence of the company in American jewelry design: Tiffany & Co. began as a stationery store but soon expanded to dominate the diamond market. And one historical connection with respect to the abolition of slavery can be found in the company's documented history of acting as an "emporium of military supplies" for the North during the Civil War.

The collection's most popular heart-modeled items — the Elsa Peretti "Open Heart" and the iconic "Return to Tiffany" collection — were introduced in or around 1969. Early Tiffany & Co. pieces antedating those now popular items (based on two separate heart designs) bear no resemblance to modern silver necklaces, chokers, or bracelets. Early pieces attributed to the brand appear to have been be more focused on displaying precious gemstones, and no piece resembling a slave collar is present among the company's historical items.

Tiffany & Co. maintains its own image repository of antique pieces, and no collar-like items appear among its archival collection of necklaces. All items resembling the choker are linked with post-1969 collections largely designed by Elsa Peretti and Paloma Picasso. In the 1800s, Tiffany & Co.'s primary precious metal works were household items such as silverware; items designed by Charles Lewis Tiffany weren't typically plain silver affairs, and all the antique chokers we located were gemstone-based.

Although no direct link appears between Tiffany & Co.'s modern heart designs and slave chokers, company founder Charles Lewis Tiffany purportedly had links to the antebellum practice of slavery. A 2002 Hartford Courant article examined the iconic brand and its roots in the trade of a less precious material — cotton:

Charles L. Tiffany originally sold goods in the company store to workers in his father's cotton mills in the hills of 19th century Connecticut, in a town named Killingly. He and the son of another mill owner bet a $1,000 stake they could make it in New York City.

That $1,000 investment — about $15,000 in today's dollars — is the start of just one of many strands of wealth created by the booming New England textile industry in the 19th century, an explosion that helped turn Connecticut from a colonial outpost of farms and villages into a center of manufacturing and international trade. Behind this transition were men of ingenuity and vision who invented the machinery, built the mills and developed revolutionary industrial processes.

And what made it all possible were hundreds of thousands of slaves who, toiling for free under even worse conditions but at a convenient distance hundreds of miles away, provided the raw material: Cotton.

The fortunes of Charles Tiffany and John Young and countless others who made names for themselves in Connecticut as merchants, manufacturers and traders have their roots in what Charles Sumner, abolitionist and later a senator from Massachusetts, called an "unhallowed union ... between the cotton planters and fleshmongers of Louisiana and Mississippi and the cotton spinners and traffickers of New England — between the lords of the lash and the lords of the loom."

The story of Tiffany's origins in the cotton trade does not appear in company history. Company President William R. Chaney was in Clinton recently preparing for the grape harvest at Chamard, the vineyard owned by his family.

He sat in the reproduction of a French manor house where the wine is fermented, bottled and sold. Chaney, who came to Tiffany's from Avon Products in the 1980s, said he had never heard of the Killingly connection and looked startled and hurt at the idea of the company's roots.

"Are you sure?" he asked.

The provenance of the viral Tiffany & Co. slave collar pictured above is certainly muddled. The image of the "slave collar from the 1700s" (of unknown origin) is from a real exhibit, albeit often misrepresented as depicting a piece on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. (rather than the Lest We Forget Black Holocaust Museum of Philadelphia). A curator explained that such items were supposedly often gifted to mistresses for use with their slaves but correctly noted that the history of slavery is often documented forensically in an absence of surviving written records, so little else is definitively known about the collar.

The web site for Colonial Williamsburg reports that affluent Americans owners sometimes placed collars made of precious metal on their slaves as status symbols:

Before slavery was outlawed in England in 1772, some slave owners had their household slaves wear a silver collar engraved with the owner's name and address. Such a collar can be seen on a slave boy in plate two of Hogarth's Harlot's progress. Affluent Americans copied this fashion. In the portrait of young Maryland resident, Henry Darnall III, painted by Justus Englehardt Kuhn, a black servant wears a wide silver collar about his neck. In Virginia, the estate of Colonel Thomas Bray included "a Silver Collar for a Waiting Man" which was sold at auction near Williamsburg in 1751. A neck ornament of precious metal that might in one context be a mark of wealth in the wearer instead indicates servitude, which by extension enhances the status of the owner.

According to the Smithsonian, slave collars made of iron were used to "discipline and identify slaves who were considered risks of becoming runaways," but their pictured example looks significantly different than the museum piece shown above:

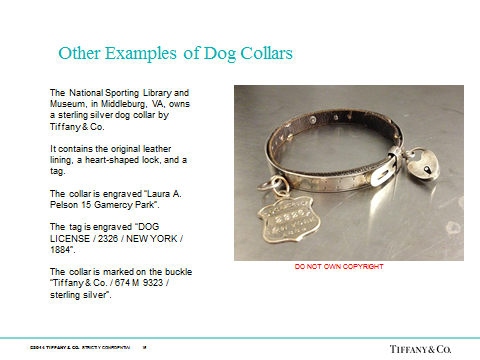

Tiffany sent along a picture showing an object very much visually like the museum "slave collar," this one identified as a sterling silver dog collar made by Tiffany circa 1884:

The museum piece indeed bears resemblance to Tiffany & Co.'s "Return to Tiffany" collection, and discomfort with that visual likeness is one reason viewers have reacted negatively to the rumor positing a connection between the two. However, Tiffany & Co. pieces from the period of time Charles Lewis Tiffany headed the company (from 1837 until his death in 1902) tend to be based on expensive gemstones, diamonds, or silverware; the company didn't commonly adopt their now-iconic simple silver heart designs until around 1969. But Tiffany's core fortune (on which he built his empire) supposedly involved pre-Civil War cotton industry wealth likely derived in part from slave labor, a detail often elided from official histories of Tiffany & Co.