In the midst of a September 2017 debate over whether the propriety of NFL players' engaging in protests during the playing of the U.S. national anthem, a book excerpt was circulated online that brought to light the movie industry's attempt to downplay criticism against Nazi Germany in the 1930s:

The excerpt featured a quote attributed to Frank Pope, who was then the managing editor of the entertainment industry trade publication The Hollywood Reporter (THR), from a column he wrote in 1937 chiding film stars for speaking out on political issues:

"The Hollywood stars who are so earnest -- and so public -- in their sympathies for anti-Nazism, anti-fascism and other antis, are doing more harm to themselves than good to the causes they sponsor," insisted columnist Frank Pope in the Hollywood Reporter. "How long will it be before the unpopularity which they certainly will gather, in some countries, will begin to affect their screen standing and, later perhaps, their salaries?"

Both the quote and the excerpt were taken from a real book, Thomas Patrick Doherty's Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939, published in 2013.

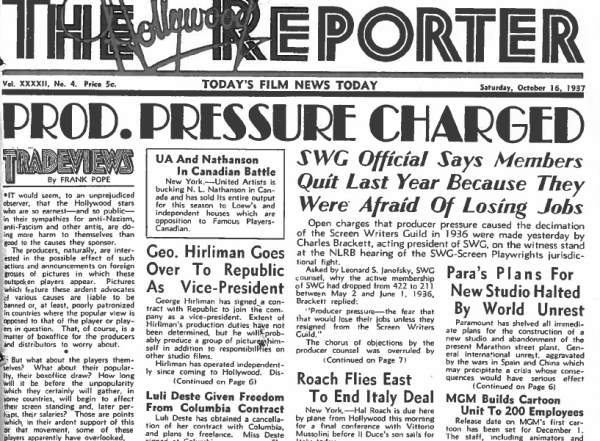

Doherty and THR both sent us pictures of Pope's column as it was originally printed on the front page of the Reporter on on 16 October 1937:

Doherty, a professor of American Studies at Brandeis University, told us that Pope's viewpoint represented the "mainstream opinion" of Hollywood distributors and film moguls at the time, as the movie industry was leery of portraying Nazis in a negative light to avoid alienating what was then the second-largest film market in the world.

However, Doherty said, opposition to the Nazis from within the film industry led to the formation of what was called the "popular front," a loose alliance of actors and screenwriters who engaged in off-screen activism. The increased political activity among this group led to the formation of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League in 1936:

This was a group that wanted to raise American consciousness about Nazism and they incorporated a lot of Hollywood stars and screenwriters and directors to get publicity for their cause. The segment that was going around on the Twittersphere was about how the studio moguls who looked upon, especially, their stars as their own private property that they had nurtured and developed were leery of having the stars use their star charisma for a political cause. Because at the time, the thinking was, "If you want to send a message, use Western Union." And they looked upon the stars as their kind-of private property.

Doherty also noted that any type of activism in the film industry was "really new" for the time and carried a particular political risk for studios because of the restrictions set forth by what was popularly known as the Hays Code:

This was at a time when the government could censor movies. Film had no First Amendment rights. Any time the film industry kind of pressed against the government, there was always the fear that the government would found a federal motion picture censorship bureau, which they could have done before 1952 when the Supreme Court gave film First Amendment rights.

The high court extended those rights to the motion picture industry in its unanimous decision in Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, which stated:

Under the First and Fourteenth Amendments, a state may not place a prior restraint on the showing of a motion picture film on the basis of a censor's conclusion that it is "sacrilegious."

Doherty added that the Reporter was also a different kind of publication at the time Pope's column was published:

They really just spoke to the industry in the 1930s. It was much more of an inside newsletter for the people in the motion picture business. They're really just talking to themselves without the sense that anybody's eavesdropping. Of course, today everybody gets The Hollywood Reporter online or checks the motion picture box office on Monday morning. It's really not a private conversation the way it was in the 1930s.

Even though studios can not overtly dissuade actors from taking political stances, he said, discussions of the potential impact on them for doing so continue:

I don't think anyone would say that George Clooney shouldn't speak up for what he believes in. But there is a lot of talk even today in Hollywood about what effect that has on the box office. If you read the chatrooms both at Deadline Hollywood or The Hollywood Reporter it's kind of difficult to quantify the blowback that an actor extratextural activity will have on the text in the movies. For some actors I don't think it matters -- Clint Eastwood, I don't think liberals go to his movies but he's such an icon.

But there's a lot of talk about, say, Clooney's movies maybe not scoring with the popular audience the way they used to because he's such an up-front liberal. I would imagine there's a lot of talk in executive boardrooms about this but they can't squash these stars the way they did in the 1930s because they're not under permanent contract to Warner Brothers or MGM.

On 9 August 2013, THR published a lengthy excerpt from another book, The Collaboration: Hollywood's Pact with Hitler, chronicling not only the film industry's hands-off policy toward Nazis, but a Senate probe into allegations that Hollywood had reversed course after World War II had begun and promoted anti-Nazi themes in order to draw the U.S. into the conflict:

The most dramatic moment came when the head of 20th Century Fox, Darryl F. Zanuck, gave a rousing defense of Hollywood: "I look back and recall pictures so strong and powerful that they sold the American way of life, not only to America but to the entire world. They sold it so strongly that when dictators took over Italy and Germany, what did Hitler and his flunky, Mussolini, do? The first thing they did was to ban our pictures, throw us out. They wanted no part of the American way of life."

In the thunderous applause that followed, no one pointed out that Zanuck's own studio had been doing business with the Nazis just the previous year.