Researchers identified a spike in maternal mortality in Texas between 2011 and 2014, while state statistics demonstrated a steady climb in such deaths beginning in approximately 2003.

Researchers did not demonstrate a direct correlation between reproductive health laws in Texas and the maternal mortality rate.

The impact of funding cuts on Texas' maternal mortality rate between 2011 and 2014;, and what factors led to steady increases prior to those legislative actions.

On 20 August 2016, the UK newspaper The Guardian (among others) published an article about a September 2016 study suggesting that the maternal mortality rate in Texas had doubled in recent years (outstripping that of countries with overall poorer health outcomes):

The rate of Texas women who died from complications related to pregnancy doubled from 2010 to 2014, a new study has found, for an estimated maternal mortality rate that is unmatched in any other state and the rest of the developed world.

The finding comes from a report, appearing in the September issue of the journal Obstetrics and Gynecology, that the maternal mortality rate in the United States increased between 2000 and 2014, even while the rest of the world succeeded in reducing its rate. Excluding California, where maternal mortality declined, and Texas, where it surged, the estimated number of maternal deaths per 100,000 births rose to 23.8 in 2014 from 18.8 in 2000 — or about 27%.

But the report singled out Texas for special concern, saying the doubling of mortality rates in a two-year period was hard to explain “in the absence of war, natural disaster, or severe economic upheaval”.

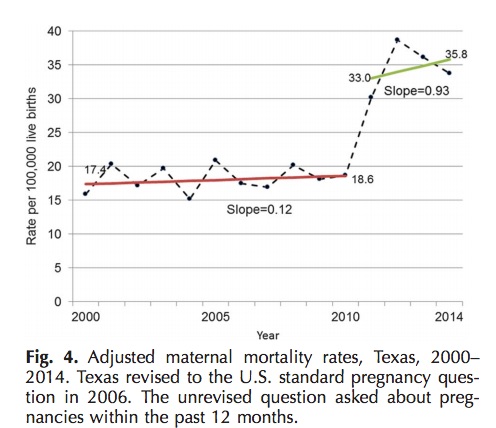

From 2000 to the end of 2010, Texas’s estimated maternal mortality rate hovered between 17.7 and 18.6 per 100,000 births. But after 2010, that rate had leaped to 33 deaths per 100,000, and in 2014 it was 35.8. Between 2010 and 2014, more than 600 women died for reasons related to their pregnancies.

No other state saw a comparable increase.

The article noted that reproductive health advocates placed the blame squarely on Texas' unique targeting of reproductive health centers and practices, citing budget cuts, atypically strict reproductive health laws and efforts to defund Planned Parenthood, along with the vast size of the state (which made it difficult for many women to cross state lines to obtain gynecological care unavailable in Texas):

In the wake of the report, reproductive health advocates are blaming the increase on Republican-led budget cuts that decimated the ranks of Texas’s reproductive healthcare clinics. In 2011, just as the spike began, the Texas state legislature cut $73.6m from the state’s family planning budget of $111.5m. The two-thirds cut forced more than 80 family planning clinics to shut down across the state. The remaining clinics managed to provide services — such as low-cost or free birth control, cancer screenings and well-woman exams — to only half as many women as before.

Not everyone was convinced the ostensible cause and effect was so clear cut, as noted in a Townhall piece holding that conclusions about Texas' legislative efforts were politically motivated and contradicted by data:

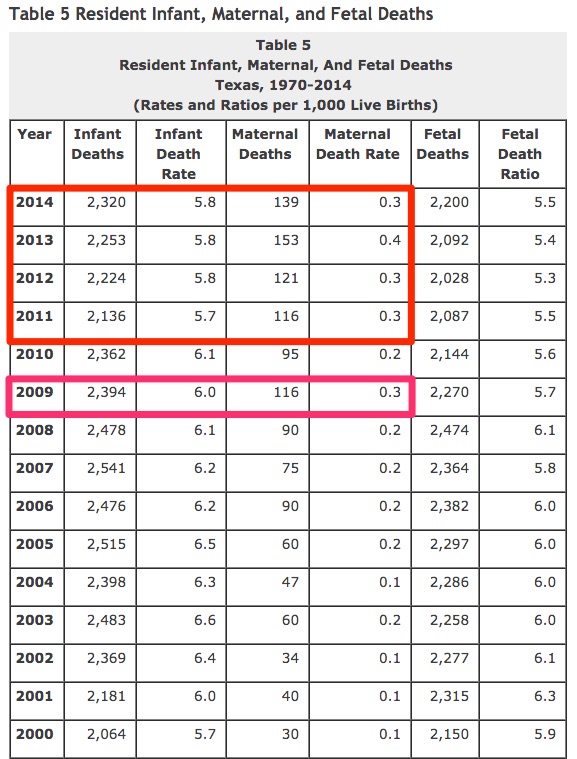

Apparently, the researchers did some adjusting of their own. According to the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS), maternal mortality rates have been alarmingly increasing for years. That “modest increase,” lead researcher Marian MacDorman imagines, was a huge increase. In 2000, the MMR was 10.5 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births (equating to 30 tragic deaths). By 2009, this rate had nearly tripled to 28.9 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births (resulting in 116 deaths). That’s a “modest increase”? In 2010, the MMR actually decreased to 24.6.

Then, MacDorman et al claimed: “Texas had a sudden increase in 2011-2012.” If by sudden they mean over ten years of significant increases ... sure. They completely ignored the fact that from 2010 to 2011, the MMR rose from 24.6 to 30.7 (an increase of about 25 percent). From 2011 to 2012, the increase was only 3%, rising to a rate of 31.6 ... not doubling! That didn't stop Slate.com and a host of media outlets from declaring: “After Texas Slashed Its Family Planning Budget, Maternal Deaths Almost Doubled.” In 2013 it rose another 25 percent to 39.5 (claiming the lives of 153 women).

Here’s the clincher, though. Texas’ MMR dropped in 2014 in rate and total maternal deaths. Neither the “peer-reviewed” study nor any of the leftists in the news media mention this.

Both items cited the study, titled "Recent Increases in the U.S. Maternal Mortality Rate" published [PDF] in the September issue of the journal Obstetrics and Gynecology. Both the study's title and its objective described a nationwide focus on maternal mortality:

To develop methods for trend analysis of vital statistics maternal mortality data, taking into account changes in pregnancy question formats over time and between states, and to provide an overview of U.S. maternal mortality trends from 2000 to 2014.

Similarly, its conclusion singled out no state by name and made no specific reference to Texas:

Despite the United Nations Millennium Development Goal for a 75% reduction in maternal mortality by 2015, the estimated maternal mortality rate for 48 states and Washington, DC, increased from 2000 to 2014; the international trend was in the opposite direction. There is a need to redouble efforts to prevent maternal deaths and improve maternity care for the 4 million U.S. women giving birth each year.

Texas' second namecheck in the study was benign, noting that the overall rate of maternal mortality was so low that only California and Texas served as sources of by-state data — due not to their specific outcomes, but to the size of their populations:

It would be preferable to analyze data individually for each state; however, maternal death is a rare event, and the number of cases (396 U.S. deaths in 2000 and 856 in 2014) was not sufficient to support individual state analysis for all but the most populous states (California and Texas).

But the "Results" portion of the introductory page noted that California's and Texas' statistics trended differently and provided a primary finding that colored media coverage of the findings:

The estimated maternal mortality rate (per 100,000 live births) for 48 states and Washington, DC (excluding California and Texas, analyzed separately) increased by 26.6%, from 18.8 in 2000 to 23.8 in 2014. California showed a declining trend, whereas Texas had a sudden increase in 2011–2012. Analysis of the measurement change suggests that U.S. rates in the early 2000s were higher than previously reported.

Much of the research hinged on pinpointing and adjusting for what was described as "the pregnancy question" (which was "added to the 2003 revision of the U.S. standard death certificate"), defined by the World Health Organization as death certificate language recording "The death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and the site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes." The WHO also provided for late maternal deaths via a separate but similar checkbox: "The death of a woman from direct or indirect obstetric causes more than 42 days but less than 1 year after termination of pregnancy." Although the phrasing "termination of pregnancy" typically is understood to mean "an abortion" in layman's speech, the researchers and WHO used it to mean the end of a pregnancy via live birth, stillbirth, miscarriage, or abortion.

Researchers noted that state-by-state adoption of the pregnancy question vis a vis death records led to findings that required some adjustment to reach conclusions. While some states immediately adopted the guideline in 2003, others waited years. By January 2014, 44 states and the District of Columbia included the question on their death certificates; that incongruous state-by-state data pool led to efforts on the researchers' parts to calibrate the data and parse it. The study noted that Texas (which adopted the question in 2006) demonstrated results that led to "uncertainty" in the final report:

California is the only state that revised their death certificate with a pregnancy question inconsistent with the U.S. standard. The California question only asks about pregnancies within the past year. In addition, there were changes over time in specific data provided by California to the National Center for Health Statistics for deaths at less than 42 days, making use of this measure impracticable. Thus, maternal and late maternal deaths were combined for the California trend analysis. Finally, we estimated maternal mortality rates for 48 states and the District of Columbia from 2000 to 2014. California and Texas were excluded from this estimation: California because it does not provide comparable data and Texas as a result of uncertainty regarding recent trends (see “Results”).

In that section, researchers described Texas' atypical spike in maternal mortality and noted that the laws in question were not likely sufficient to account for the spike (referencing a "future study" to obtain more information on Texas):

Texas had an unrevised question about pregnancies in the past 12 months and revised to the U.S. standard question in 2006. Adjusted maternal mortality rates for Texas show only a modest increase from 2000 to 2010, from a rate of 17.7 in 2000 to 18.6 in 2010. The slope of this regression line was 0.12 (95% CI 20.22 to 0.46) (564 maternal deaths and 4,246,835 live F4 births) (Fig. 4). However, after 2010, the reported maternal mortality rate for Texas doubled within a 2-year period to levels not seen in other U.S. states. Joinpoint trend analysis was done separately for the 2000–2010 and the 2011–2014 periods because the trends for these two periods differed widely.

The Texas data are puzzling in that they show a modest increase in maternal mortality from 2000 to 2010 (slope 0.12) followed by a doubling within a 2- year period in the reported maternal mortality rate. In 2006, Texas revised its death certificate, including the addition of the U.S. standard pregnancy question, and also implemented an electronic death certificate. However, the 2006 changes did not appreciably affect the maternal mortality trend after adjustment, and the doubling in the rate occurred in 2011–2012. Texas cause-of-death data, like with data for most states, are coded at the National Center for Health Statistics, and this doubling in the rate was not found for other states. Communications with vital statistics personnel in Texas and at the National Center for Health Statistics did not identify any data processing or coding changes that would account for this rapid increase. There were some changes in the provision of women’s health services in Texas from 2011 to 2015, including the closing of several women’s health clinics. Still, in the absence of war, natural disaster, or severe economic upheaval, the doubling of a mortality rate within a 2-year period in a state with almost 400,000 annual births seems unlikely. A future study will examine Texas data by race–ethnicity and detailed causes of death to better understand this unusual finding.

The study's introduction cited "[e]arlier studies [which] identified significant underreporting of maternal deaths in the National Vital Statistics System," reiterating in its "Discussion" section that variations by state impeded the research:

For example, had the National Center for Health Statistics and the Texas vital statistics office both been publishing annual maternal mortality rates, the unusual findings from Texas for 2011–2014 would certainly have been investigated much sooner and in greater detail.

The study noted that Texas demonstrated what appeared to be a spike in maternal mortality between 2011 and 2014, but researchers weren't yet confident that slashed funding for women's healthcare was primarily responsible for the change. Moreover, researchers mentioned widespread underreporting of maternal mortality across all states, positing it was "an international embarrassment that the United States, since 2007, has not been able to provide a national maternal mortality rate to international data repositories such as those run by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development." Study author Christine Morton told a reporter that the Texas-specific findings remained an unsolved puzzle:

I think everybody is at a loss to understand why Texas saw such an increase in maternal mortality rate. We posited that the documented changes in provisions in women's health services happened in this same time period, but it's hard to know—in the absence of in-depth case review of maternal mortality data in Texas—how that lined up with those changes.

As the Townhall columnist pointed out, Texas did demonstrate upticks in maternal mortality antedating 2011 clinic funding provisions. State data from 1970 to 2014 evidenced the 2011 to 2014 spike in maternal mortality but exhibited a maternal death rate (a number unaffected by the raw number of deaths or births in any given year) that didn't appear to correlate directly with changes in state laws. In 1970, the maternal death rate hovered at 0.3 per 1,000 live births, dropping to 0.1 in 1977 and remaining virtually static until it rose to 0.2 in 2003. That figure remained fairly constant until 2009, when it reached 0.3 at 116 deaths; 2011 saw identical numbers. In 2012, 2013, and 2014 respectively that rate was 0.3 (121 deaths), 0.4 (153 deaths), and 0.3 (139 deaths):

So the September 2016 study on the United States' maternal mortality rate published in the journal Obstetrics and Gynecology identified a steady increase in maternal deaths in Texas and cited state laws and funding as a potential (not proven) factor in that post-2011 uptick. But study authors bemoaned a lack of comprehensive record-keeping nationwide that impeded research, and the first year maternal deaths began increasing in Texas was 2003 (before clinics were affected by legislative efforts to reduce abortion).