One of the constitutional powers of the President of the United States is to nominate and appoint judges of the Supreme Court, with the qualification that such appointments be undertaken with the "advice and consent of the Senate." This procedure — like many others crafted by Founding Fathers who did not anticipate the rise of political parties in America — has long since become enmeshed in partisan posturing. Whichever party holds the White House typically seeks to elevate a Supreme Court nominee who is ideologically aligned with their party, employing varying strategies to push their chosen nominee through the approval process depending upon whether they, the opposition, or neither party controls the Senate.

One uncommon (but not unprecedented) circumstance presaging a Supreme Court battle occurred when Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia unexpectedly passed away on

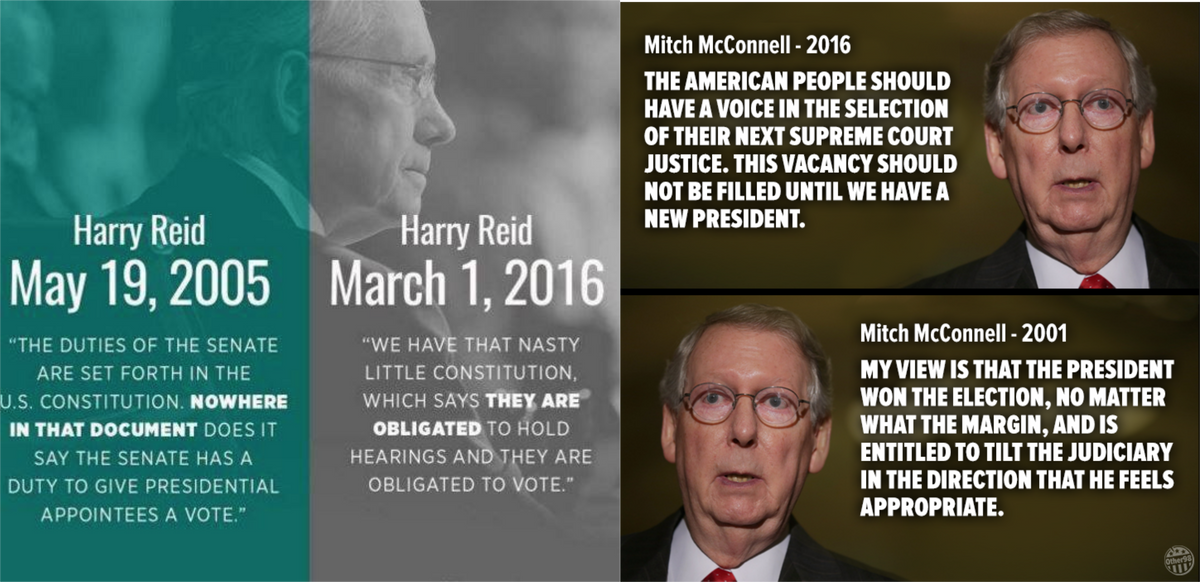

This chain of events, naturally, prompted criticisms about one side's "playing games" with the Supreme Court confirmation process and the other side's engaging in hypocrisy for objecting to something they themselves had advocated on previous occasions. This rhetorical battle was reflected in various images circulated by social media that portrayed members of both parties as opportunistic flip-floppers who justified whichever approach suited their side at the time.

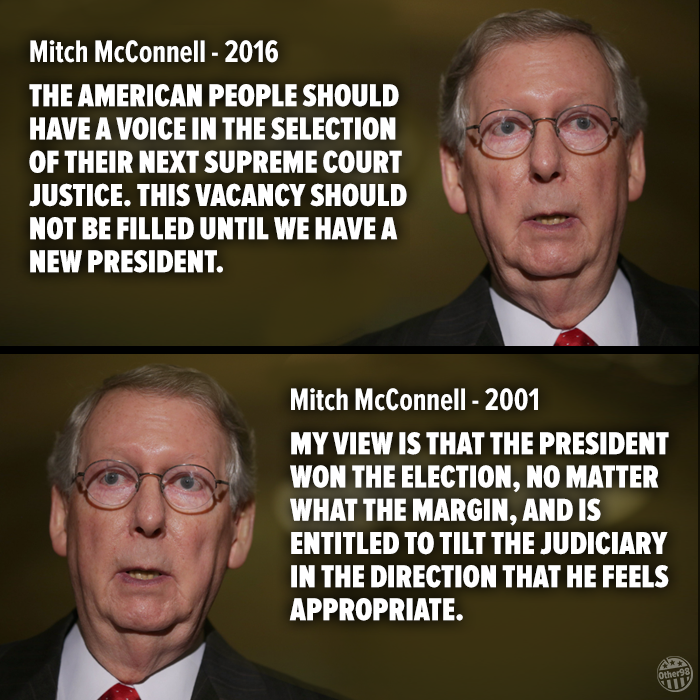

One such image featured quotes from Mitch McConnell, the Senate Majority Leader (and a Republican), advocating (in 2016) that Scalia's seat remain open until after the next presidential election, while stating (in 2001) that the President "is entitled to tilt the judiciary in the direction that he feels appropriate":

2016: The American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court Justice. Therefore, this vacancy should not be filled until we have a new president.

2001: My view now is that the President won the election, no matter what the margin, and is entitled to tilt the judiciary in the direction that he feels appropriate.

Verifying the accuracy and meaning of the first quote is fairly straightforward: On 13 February 2016 (the day Scalia died), McConnell's words were widely reported

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said the Senate should not confirm a replacement for Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia until after the 2016 election — an historic rebuke of President Obama's authority and an extraordinary challenge to the practice of considering each nominee on his or her individual merits.

The swiftness of McConnell's statement — coming about an hour after Scalia's death in Texas had been confirmed — stunned White House officials who had expected the Kentucky Republican to block their nominee with every tool at his disposal, but didn't imagine the combative GOP leader would issue an instant, categorical rejection of anyone Obama chose to nominate.

"The American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court Justice. Therefore, this vacancy should not be filled until we have a new president," McConnell said, at a time when other elected officials, from Sen. Bernie Sanders to future Senate Democratic Leader Charles Schumer, were releasing statements offering condolences to the justice's family, which includes 26 grandchildren.

The second quote stemmed from hearings held in 2001 by a Congressional Subcommittee on Administrative Oversight and the Courts regarding the judicial nomination and confirmation process (for all federal judicial appointments, not just Supreme Court justices), hearings that "focused on the vital question of what role ideology should play in the selection and confirmation of judges."

Senator McConnell, as a member of the Committee on the Judiciary, averred (in part) that the role of the Senate should largely be to examine "the competence and the integrity and the fitness of a judge to be on the bench" rather than a nominee's political ideology, that the Senate should "defer to the President on the question of ideology," that the President is "entitled for the most part to tilt the judiciary in the direction that he feels appropriate," and that he (i.e., McConnell) had accordingly approved every one of judicial nominees put forth by President Bill Clinton (a Democrat):

I first began to deal with the Senate's advise and consent role as a staffer here in 1969 and 1970 to a member of this Committee during the Haynesworth and Carswell nominations, and subsequently wrote the only law journal article I wrote as a young man on that subject after those contentious nominations were concluded. I believed then and believe now that the appropriate role of the Senate is largely as Senator Kyl suggested, which is to judge the competence and the integrity and the fitness of a judge to be on the bench.

I dutifully returned, gagging occasionally, every single one of the blue slips I received during the Clinton years positively. My view then and my view now is that the President won the election, no matter what the margin, and is entitled for the most part to tilt the judiciary in the direction that he feels appropriate.

What I fear is going on with the hearing today is trying to establish a new litmus test for the Senate that has not existed in the past. I don't understand why we are seeking to do that. As Senator Sessions pointed out, and I think Senator Kyl alluded to this as well, 377 of President Clinton's nominees were approved. During 75 percent of his term, there was a Republican Senate here. During President Reagan's years, during which he had during 75 percent of his tenure in office a sympathetic Senate, only a few more were confirmed, 382.

That is why the safest place to be and the sound place to be and the place where the Senate has been most of the history of our country is largely deferring to the President on the question of ideology and judging the competence and the integrity of the nominee.

I doubt if the Founding Fathers were aware that there would be a Judiciary Committee. It probably never occurred to them. When they said "advise and consent," I think they were talking about the full Senate. Certainly, the Founding Fathers did not envision that there would be a bunch of co-presidents here. They did, after all, give the power to nominate to the President.

McConnell concurred with a previous statement offered by Jon Kyl, a Republican senator from Arizona, who said (in part):

I find it interesting that the argument that a candidate's ideology should be a sufficient rationale for rejection is characterized as a bipartisan approach. I would think that bipartisanship would mean quite the opposite. Cooperation with the President on a bipartisan basis I don't think begins with a threat that we are going to reject your nominees, no matter how competent they might be, if we don't like their political ideology, as we interpret it to be.

I think we should make no mistake that what is being suggested here is a significant departure from the way that nominees have traditionally been treated. Have there been exceptions? Quite assuredly so, but they prove the rule because they are exceptions to that general deference that has always been given to the President's nominees.

From a bipartisan point of view, it concerns me because I do believe it puts us on a very dangerous path of confrontation and contention here within the Congress, as well as in our relationship with the President, and also, as Senator Sessions has said, creates a very bad precedent.

I also found it interesting that the Chairman alluded to President Bush's campaign theme and frankly the reaction to that by his opponent, who made it clear that if President Bush were elected, he would be putting strict constructionists like Justice Thomas and Justice Scalia on the Supreme Court.

That, of course, I think was a correct characterization of the tradition that a President does do that. A President has that right when he is elected, and he has been elected, by the way, even though it was a close election. President Bush is the President, and I think the Democrats who campaigned against him on the basis that he would try to appoint people that were consistent with his judicial philosophy were correct in saying that he would do that, that that would be the end result, because the Senate has always confirmed nominees more or less of the President elected, regardless of how close the election was. President Clinton, after all, never had a majority of the citizens of this country vote for him, but we gave significant deference to his nominees.

My point is that for us as political figures — and this is our milieu, politics — to try to translate our political views onto a Court's job and maintain balance by our confirmations, I think, is sheer folly. Instead, we should all revert to what has traditionally been our role, judging the competence of the candidate; the qualifications, including judicial temperament, the background; and also some look at judicial philosophy.

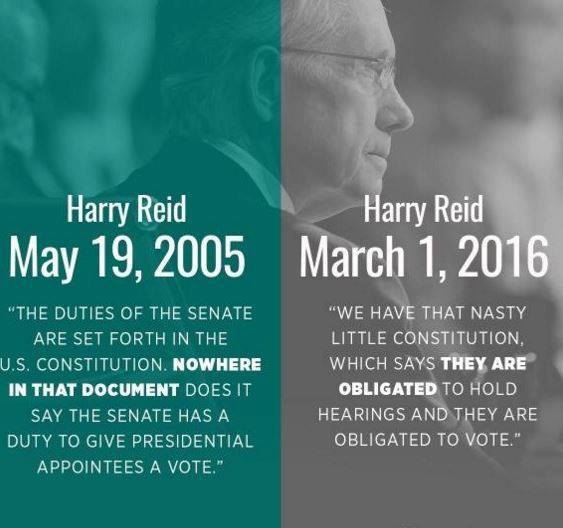

Another image featured similar "flip-flopping" statements from Senator Harry Reid of Nevada, a Democrat who previously served as Senate Majority Leader:

The duties of the Senate are set forth in the U.S. Constitution. Nowhere in that document does it say the Senate has a duty to give presidential appointees a vote. [19 May 2005]

We have that nasty little Constitution, which says they are obligated to hold hearings and they are obligated to vote. [1 March 2016]

As with the McConnell image, the quotes attributed to Reid were contradictory and presumably based on whatever course of action might be politically expedient for his party rather than on a consistent (non-partisan) political position. The provenance of these statements was also not difficult to ascertain: On 1 March 2016, Reid was quoted as follows in an article about Republican opposition to holding nomination hearings for Scalia's replacement prior to the end of President Obama's term:

Before he traveled along Pennsylvania Avenue to the White House, [Senator] McConnell told House Republicans at their weekly meeting that he's standing by his promise not to hold hearing or votes on an Obama nominee.

Scalia was the leading conservative voice on the bench, and an Obama replacement could give liberals a five-vote majority.

The president "made it very clear" in the meeting that he would consider any nominees recommended by McConnell and Grassley, according to Reid. But the GOP leaders did not offer up a list of names.

Asked what leverage Democrats have to force a vote, Reid suggested they would continue to shame Republicans over their stance.

"We have that nasty little Constitution, which says they are obligated to hold hearings and they are obligated to vote," he said. "They swore to uphold the Constitution. They're not doing that. They are walking away from that."

(Technically, the Constitution simply states that the President "shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint ... Judges of the supreme Court"; that document is silent on whether the Senate is obligated to hold hearings and vote on such nominations.)

Evidence of Sen. Reid's 2005 statements was equally easy to come by: During a 19 May 2005 Senate session convened in consideration of the appointment of Priscilla Owen as a judge for the Fifth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals (which had, among other similar nominations, been blocked by filibustering Democrats):

The Senate continued consideration of the nomination of Priscilla Owen as a judge for the Fifth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals.

She was the first of seven nominations which had been filibustered by the Democrats, the minority party. The Republicans, who held a 55-vote majority, had proposed changing the confirmation process through a ruling from the President of the Senate, upheld by a majority of Senate, that votes on judicial nominees not be subject to a filibuster. This would be a change in the Senate rules which would allow confirmation by a simple majority vote without having to invoke cloture on debate. This was popularly referred to as the "nuclear option" because of its potential impact on the normal procedure of business in the Senate.

Debate was evenly divided by time blocks allocated to each party.

During those proceedings, Senator Reid maintained the wording of the Constitution did not require that "every nominee receive a vote":

The duties of the Senate are set forth in the U.S. Constitution. Nowhere in that document does it say the Senate has a duty to give Presidential nominees a vote. It says appointments shall be made with the advice and consent of the Senate. That is very different than saying every nominee receives a vote.

A minor quibble could be made about Reid's speaking of judicial "nominees" and not Supreme Court "appointees," but that difference seemingly had little bearing on the overall thrust of his statement.