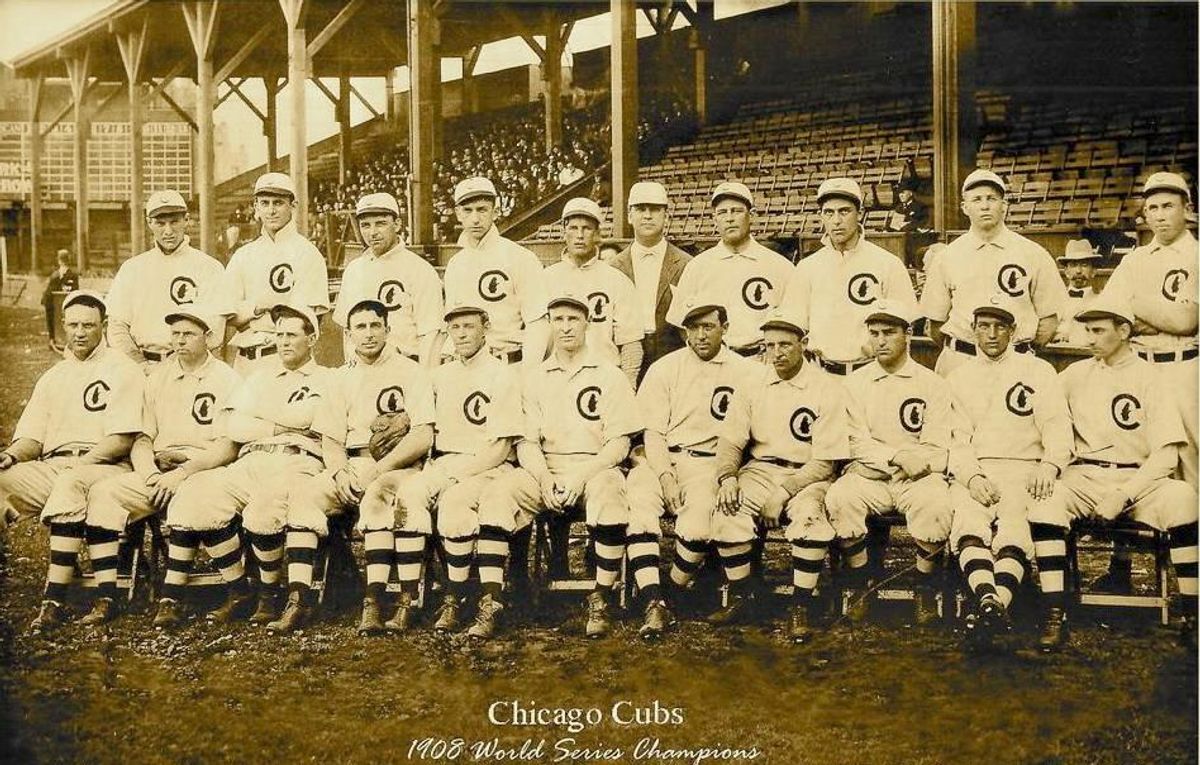

Few tangible elements remain of the 1908 baseball season: The players who took part in it, the reporters who covered it, and the fans who followed it have all passed away; the ballparks that hosted its contests have long since been torn down; and that pre-radio, pre-television era produced no recordings or broadcasts through which those long-ago games might be recreated for modern audiences. Virtually all we have left to bear witness to the events of that season are century-old newspaper accounts and box scores, the memoirs of long-dead participants, and a clutch of black-and-white photographs.

Nonetheless, what remains of that 1908 baseball season suffices to inform us that those who lived through it witnessed one of the most exciting pennant races in the history of major league baseball: A three-team, season-long chase among the Chicago Cubs,

What makes the 1908 season especially remarkable is that the final Cubs-Giants game was not technically a playoff (i.e., an extra game tacked onto the end of a season to break a tie), but rather a replay of a contest that had been waged two weeks

On 23 September 1908, as the Cubs and Giants squared off for the third game of a four-game series at the Polo Grounds, the two teams were even in the standings (Chicago having erased New York's two-game lead by sweeping a double-header from the Giants the previous day), with the Pittsburgh Pirates breathing down both their necks. That third contest went into the bottom of the ninth inning with the score knotted at

It was not to be, though. When the Giants' first-base runner, Fred Merkle, saw the winning run cross the plate, he instinctively veered out of the basepath and headed towards center field in order to reach the clubhouse before a crush of delirious

The two umpires working the game sided with the Cubs

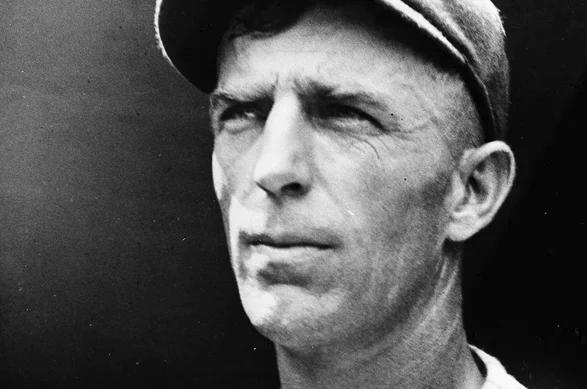

Fred Merkle

Fred MerkleEvery recounting of the 1908 National League pennant race focuses on the "Merkle game," but whenever teams finish a long campaign locked in a tie, one can look back across all the year's games and find numerous instances of errors, miscues, lapses in judgment, bad officiating calls, and just plain bad luck, any one of which could have changed the season's final outcome had it turned out differently. Indeed, one such incident which took place near the end of 1908 season spawned its own urban legend.

On 4 October 1908, the Pittsburgh Pirates played their final game of the season against the Cubs in Chicago. Going into that contest, the Pirates held a slim half-game lead over the Cubs, and a one-and-half-game lead over the New York Giants. Had Pittsburgh emerged victorious that day, they would have eliminated the Cubs from pennant contention and forced the Giants to win their final four games of the season just to finish in a first-place tie. (As things turned out, the Giants won the first three of their remaining contests and then lost the

The Pirates' final-game loss was not without its drama, however. Trailing by three runs in the top of the ninth inning, Pittsburgh had a runner on first when second baseman Ed Abbaticchio swatted a pitch into the crowd behind right field. The umpire (coincidentally the same one who had officiated at the infamous "Merkle game") ruled the ball foul, while the Pirates protested that it was fair and should have counted for at least a double and possibly a home run, thereby bringing the tying run up to the plate. Pittsburgh lost the argument and shortly thereafter the game, and with both their shot at the pennant.

Although a World Series appearance for the Pittsburgh Pirates did not follow the 1908 season, an urban legend did. According to rumor, a few months after that heartbreaking Pirates-Cubs game, a woman who attended the contest sued the Chicago Cubs ball club, claiming she had been struck by the ball hit by Ed Abbaticchio in the ninth inning and had been so seriously injured that she required hospital treatment. The kicker to the rumor was that the ticket stub the plaintiff produced to demonstrate her presence at the game showed her to have been sitting (or standing) in fair territory at the time, and thus her claim definitively proved that the umpire had blown the call by ruling the ball foul, thereby costing the Pirates a fair shot at the championship:

In late September [1908] the third team in the National League race, the Pirates, was playing the Cubs. In the ninth inning, with Chicago ahead

2-0 and the visiting Pirates at bat with the bases loaded, second baseman Ed Abbaticchio hit a rocket down the right-field line. [Umpire Hank] O'Day ruled it foul, the Cubs won the game, and went on to win the pennant by one game over the Pirates as well as taking the playoff from the Giants.Several months later, though, a woman fan brought a lawsuit to court, alleging injury suffered when she was struck by Abbaticchio's smash, an occurrence attested to in sworn statements by various witnesses. But the court ending up ruling against

her — not because her story wasn't believed, but because it was conclusively established that she had been sitting in fair territory at the time.

More than fifty years later, this rumor (in multiple variations) remained so prevalent that in 1965 the staff of Baseball Digest undertook the challenge of determining whether any element of truth might lie behind it:

[N]obody apparently ever has been able to ascertain the name of the woman fan, the name of the judge who made the intriguing decision, or the date of the hearing.

Absence of any definite details about the lawsuit made the story smack of an old wives' tail [sic]. So the Baseball Digest staff took out its Sherlock Holmes cap and pipe and went to work.

A thorough, tedious search of all official records of all state and county courts in Chicago for two years following the game (after which the statute of limitations would preclude such a suit) failed to reveal any such lawsuit filed against the Cubs (in fact, no lawsuit against the Cubs by any fan). A day-by-day search of the Chicago newspapers from the morning after the game until well into 1911 failed to disclose any mention of any such legal action.

While 1908 legal records of both Chicago and Pittsburgh clubs have been lost in antiquity, no official of either club could recall ever having heard any mention of any such suit.

William E. Benswanger, officially associated with the Pirates from 1913 to 1946, their owner and president the last 14 of those years, and a rabid fan long before his formal association with the club, had never even heard of the story!

Lee Allen, historian of the Hall of Fame and undoubtedly today's outstanding authority on the game's history, has been unable to find any evidence of any such legal action.

The Chicago Tribune's Harvey Woodruff, one of the most respected and thorough reporters of all time, never even mentioned any fan's being hurt at the

game — though he wrote dozens of notes as well as the long lead story on the contest [and even recorded that a woman had gone into labor and given birth in the stands during the game].It is reasonable to assume that Woodruff, alert and thorough enough to record the intimate details of an accouchement in the grandstand, certainly would have reported any excitement in the crowd occasioned by a woman's being hit by a line

drive — especially on a key play of the game.

The Digest also noted that it would have been particularly silly for the Chicago ball club to have taken such a minor case to court rather than settling it, especially since (whatever the verdict) it would have demonstrated their championship season to have been tainted and would have proved highly embarrassing to an umpire who would be officiating at their games for years to come.

As satisfying as this legend may once have been to fans of that long-ago Pittsburgh club, the plainer truth is that the Pirates lost the 1908 pennant because the Chicago Cubs were the better team on the field that day.