The assertion that COVID-19 is the byproduct of work performed at or by the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) has reportedly gained credibility in recent months. "Since last year, the lab-origin story has gained new converts and respectability," Paul Farhi and Jeremy Barr wrote in a June 2021 Washington Post column, thanks in part to journalists "who have taken a fresh look at the limited evidence that has dribbled out over the past year."

Snopes does not seek to prove or disprove a laboratory origin for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Instead, Snopes challenges the notion that the "evidence" propelling this purported change in narrative is valid. Overwhelmingly, this alleged new information principally stems from a series of self-referential blog posts. That body of work generally repeats the same broad scientific arguments, despite the fact that all the posts — at least in part — rely upon misinterpretations of, or false statements about, the science on which their case is built.

The story promoted by lab leak advocates is seductive: Powerful scientists unfairly rejected the notion that SARS-CoV-2 came from a lab as a conspiracy theory, but a ragtag collection of "internet sleuths" has uncovered damning information suggesting that notion is likely true. That narrative first hit the mainstream with a January 2021 New York magazine "investigation" by novelist Nicholson Baker, and in late May 2021, lab leak arguments gained renewed traction when former New York Times science journalists Nicholas Wade and Don McNeil, among others, argued that the totality of evidence made a lab leak the most likely scenario explaining the origin of SARS-CoV-2.

Contrary to these claims, we argue, this narrative is not based on evidence. It is instead based on speculation, innuendo, and overt misinterpretations of scientific research. Here, Snopes focuses on five specific areas of confusion muddying the debate about the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic.

At a Glance

- Many hypotheses explicitly or implicitly argue that a bat coronavirus (RaTG13) discovered by the Wuhan Institute of Virology is a direct ancestor of SARS-CoV-2. This is not possible, as the two viruses are separated by between 20 and 50 years of evolution.

- RaTG13-based hypotheses require a cultured specimen of the virus. There is no evidence that such a specimen has ever existed.

- Conspiratorial conclusions drawn from the renaming of RaTG13, which had portions of its genome described in past publications under its sample name Ra4991, have distorted the scientific significance of the Mojiang mine in which it was found.

- Claims that SARS-CoV-2's genome provide "smoking gun evidence" of human intervention rely on discredited arguments and quotes from notable scientific figures who have since walked those claims back.

- Lab leak advocates describe zoonotic spillover — the process by which an animal virus naturally becomes capable of infecting a human — in ways that falsely minimize its likelihood.

(The Wuhan Institute of Virology)

Background

The Wuhan Institute of Virology has been, since the first SARS outbreak in 2002-03, a premier research institute for the study of coronaviruses, the type of virus responsible for SARS, MERS, and COVID-19. The fact that this lab, which works with bat and human coronaviruses, is located in the city where COVID-19 was first detected is the central undisputed piece of evidence in support of a laboratory leak.

A WIV scientist named Shi Zhengli, now the virologist at the center of allegations that her work resulted in the COVID-19 pandemic, is often credited with having identified the bat origins of the 2002-03 SARS outbreak. SARS, caused by the virus SARS-CoV (or SARS-CoV-1), originated with a population of bats in a single cave persistently infected with what are known now as SARS-related coronaviruses (SARSr-CoV). That cave, Shi and her colleagues reported, contained bats infected with at least 15 different SARSr-COVs, and this collection of viral material — as a group — contained all the necessary genetic components to create SARS-CoV-1.

SARS became a textbook example of "zoonotic spillover," a model of emerging disease that typically requires a "reservoir species" of persistently infected animals (bats), an "intermediate host" that provides for the recombination of bat coronavirus with its own coronavirus material (civets sold in the wild animal trade, in the case of SARS), and a final host (humans involved in the trade) for whom the virus is, or evolves to become, both infectious and capable of causing disease.

On Dec. 30, 2019, after weeks of Chinese authorities’ suppressing relevant information, rumors of a new SARS outbreak first broke into the public sphere. That night, the Wuhan CDC sent samples taken from seven severe cases of what was then known as "pneumonia of unknown etiology" to Shi's lab at the WIV for identification. Early drafts of research about the new virus's genetics were published online in late January 2020. A final draft describing the full SARS-CoV-2 genome — the virus's genetic code — was published by her team on Feb. 3, 2020, in the journal Nature. Scientists and charlatans alike have been poring over those data to make arguments of varying strength ever since.

Shi's team concluded that SARS-CoV-2 was 79% identical to SARS-CoV-1 and 96% identical to a virus her team had sampled from bats in a mineshaft in 2013. This information formed the basis of the widely accepted conclusion that SARS-CoV-2's ancestor was a bat virus. The portion of the new virus's genome that differed most from the bat virus was the portion that codes for its spike protein, which researchers noted was similar to the spike protein of a pangolin coronavirus, generating the now less widely accepted hypothesis that a pangolin served as an intermediate host.

Several elements of the lab leak hypothesis claim that SARS-CoV-2 is too well adapted to humans to be natural. But they also, by and large, focus myopically on RaTG13, the virus collected by Shi in 2013 and subsequently found to be the most closely related to SARS-CoV-2. Authors of these pieces pose hypotheses that either explicitly or implicitly assume RaTG13 is a direct ancestor of SARS-CoV-2.

RaTG13 Is Not a Direct Ancestor of SARS-CoV-2

The conclusion that RaTG13 is 96% similar to this novel coronavirus is not evidence, despite its use as such by lab leak advocates, that SARS-CoV-2 evolved from RaTG13. From a basic and scientifically uncontroversial standpoint, it did not. Instead, the viruses that would eventually become SARS-CoV-2 and RaTG13 evolved from a shared viral ancestor separated by between 20 and 50 years of evolution.

An April 2020 Medium post by Yuri Deigin, a "serial entrepreneur" and founder of a startup that seeks to "defeat aging," is cited by several lab leak advocates including McNeil and Baker. In his piece, Deigin asserts that "CoV2 is an obvious chimera … based on the ancestral bat strain RaTG13." In Deigin's scenario, RaTG13 — either through laboratory manipulation or recombination in nature (the intermingling of viral genetic material in animals with multiple infections) — acquired pangolin coronavirus spike genetics.

McNeil, in a Medium post cited by The Washington Post as lending new credibility to the lab leak theory, repeated this scenario, asking "What if some Wuhan scientist did something like take the likely suspect virus RaBtCoV/4991 [RaTG13] and use it as the 'backbone' for a set of chimeras?" Baker also proffered this argument in New York Magazine: "New functional components may have been overlaid onto or inserted into the RaTG13 genome," he speculated.

This argument has a fatal flaw: SARS-CoV-2 is not, as implied, the RaTG13 virus with a section of its genome swapped out. While RaTG13 is most dissimilar to SARS-CoV-2 in the spike region, its entire genome — over 1000 nucleotide changes throughout — diverges from SARS-CoV-2 in significant ways. When people such as Deigin write that SARS-CoV-2 is as if someone "cut out" a precise portion of pangolin genetics and "inserted" it into RaTG13, they are misrepresenting the data they cite.

As University of Glasgow Professor David Robertson told HealthFeedback, "You’d have to change these other parts of RaTG13’s genome to arrive at SARS-CoV-2’s sequence." To lab leak advocates, this is no problem. They invoke vague claims about the potential for serial passage — a method of genetic manipulation performed by sequentially passing a virus through cell lines or organisms that would not typically be capable of hosting that virus — to "speed up mutations."

"What if various such chimeras [including ones with RaTG13] were passaged through cultures of human cells or humanized mice? Wouldn’t that speed up mutations into forms likely to infect humans even faster than nature can?" Don McNeil wrote. This argument, and others that invoke serial passage, are entirely speculative. Their proponents cite no quantitative evidence to demonstrate such evolutionary distance could be made up by this mechanism, and the people qualified to address the plausibility of serial passage turning RaTG13 into SARS-CoV-2's backbone in quantitative terms say that it is not possible.

Forcing RaTG13 into the role of direct ancestor to SARS-CoV-2 is also unnecessary, given what we now know about other SARS-CoV-2-related viruses. While RaTG13 remains the closest genome to SARS-CoV-2 on average, at least three other bat viruses described since the onset of the pandemic are closer in large swaths of their genomes to SARS-CoV-2. This suggests that those viruses, with no connection to the WIV, are related to a more recent ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 than RaTG13.

There is, however, an even more fundamental problem with the hypotheses presented above: They require an actual sample of a living RaTG13 specimen. There is no evidence that such a specimen has ever existed.

There Is No Evidence the Wuhan Institute of Virology 'Isolated' RaTG13

Viruses sustain themselves only in an organism's cells. Without the protection and tools of a cell, coronavirus RNA rapidly degrades in the environment, breaking down into smaller non-functional bits of RNA.

Several arguments in favor of a lab leak assert that the Wuhan Institute of Virology "isolated" the bat virus RaTG13. Isolating a virus is a process in which a fully functional virus — the complete RNA genome — is recovered from a sample containing large intact fragments of viral RNA or from a living specimen. Such a virus is then stored in compatible cell lines for use in later experimentation. This process results in a functional and potentially infectious virus kept in temperature-controlled storage.

These processes differ fundamentally from the work of sequencing a virus sourced from fecal samples taken in the field. Such samples may contain, among other things, a slush of broken and non-infectious RNA strands potentially sourced from one or more coronaviruses. The reconstruction of a viral genome from a sample like this occurs within the confines of a computer after those RNA bits have been digitally converted into short strings of nucleotide code. The end result of this process is a file on a computer, not a physical specimen capable of being leaked anywhere.

Lab leak advocates have repeatedly blurred the crucial distinction between a sequenced viral sample and an isolated virus. For example, a June 2021 blog post written by Milton Leitenberg and published by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists claimed that the WIV "possessed the virus that is the most closely related known virus in the world to the outbreak virus, bat virus RaTG13. This virus was isolated in 2013." Baker, in New York Magazine, posited that "this same virus [RaTG13] had been stored and worked on in the Wuhan Institute for years."

For what it's worth, Shi has stated that RaTG13 has never been isolated or cultured. Leitenberg attempted to cast doubt on that claim by declaring that "knowledgeable virologists assume that the number must be much higher, probably hundreds of live viral isolates." The footnote for this statement is a "personal communication" from an unknown individual.

Some members of Trump's State Department, evidently, were similarly confused about the difference between viral sequences and viral cultures. In a memo released through a Freedom of Information Act request to Vanity Fair, former Assistant Secretary for International Security and Nonproliferation Christopher Ford summarized the conclusions derived from a panel of experts who met in January 2021 to discuss the lab leak scenario. In that document, he wrote:

The assertion that WIV kept "thousands of coronaviruses" was also questioned in our discussion, since while it is true that WIV sequenced great numbers of viruses, such sequencing most commonly involves the possession of viral genomic material rather than live viruses ...

One of the panelists also noted the incredible difficulty of isolating live virus from bat samples, which are usually fecal samples, and that this is extremely unreliable and usually not successful.

It is impossible for Snopes or anyone else to prove the negative that lab leak advocates demand: that the WIV did not isolate and culture a virus from that 2013 sample. But stating as fact an unproven assertion without noting there is no evidence to support it is deceptive, especially when the totality of an argument depends upon that assertion being true.

Still, proponents of many lab leak arguments can not quit RaTG13. Yet another talking point attempts to cast the location of this virus's discovery as evidence of the hand of the WIV in the evolution or spread of SARS-CoV-2.

The 2012 Mojiang Mine Incident's Scientific Significance Has Been Distorted

In reading virtually anything written about the lab leak hypothesis, what proponents identify as the "most startling" finding is that the RaTG13 virus was originally named Ra4991. This renaming, lab leak advocates allege, was done to obscure the sample's connection to a mineshaft in southern China where workers shoveling bat guano in 2012 became ill with SARS-like symptoms and died. As Shi has explained, the new name reflects the species of bat from which the virus was collected (Rhinolophus affinis), the location where it was collected (Tongguan) and the year of the sample's collection (2013).

In an addendum to her SARS-CoV-2 genome paper published months later, Shi stated that these samples were collected after local authorities were concerned that the miners' cases could represent a novel animal-born virus. Shi's team (which was not the only group working at this site) sampled bat fecal samples once or twice a year from 2013 to 2015, collecting a total of 1,322 samples. Within those samples, Shi said in an interview with Science, nine were identified as containing betacoronaviruses, the family to which SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 belong. One of those betacoronavirus-containing samples was Ra4991.

The name change has been used to project suspicion onto Shi's work in the absence of clearly defined theories about its relevance. "Rather than 'finding' RaTG13 in her freezers in February, Dr. Shi had worked with it since at least 2016, but under a different name, RaBtCoV/4991," McNeil wrote. "This virus," he argued, using a strawman argument never presented by Shi, "had not been gathered at random but from a mineshaft in which miners digging bat guano got pneumonia, some fatally."

Deigin, in his piece, made the same argument. "It is odd that in her 2020 paper on RaTG13 Shi Zhengli fails to mention RaBtCoV/4991 or cite her 2016 paper about its discovery," he wrote. "It is not like RaBtCoV/4991 was forgotten by her group, as it is mentioned in their 2019 paper, where it is included in a phylogenetic tree of other coronaviruses." Finding things "odd" is not evidence; it is innuendo.

Innuendo is all lab leak advocates have offered on this point. Most lab leak articles cite a translated Chinese master’s thesis about the miners' illness as evidence of deception. This thesis argued that a SARS-like coronavirus may have been responsible for the deaths of the miners, but it found no definitive evidence in favor of that conclusion. In perhaps the least controversial statement of the lab leak debate, the authors who brought this translated thesis into the limelight concluded "that the Mojiang mineshaft miners' illness could provide important clues to the origin of SARS-CoV-2."

Indeed it could, but that has nothing to do with the plausibility of a lab leak. While the conclusion is disputed, let's say for sake of argument that these miners died of a bat-borne coronavirus contracted in the mine as alleged (the presence of multiple viruses and other pathogens make any such a conclusion challenging and another team of researchers proposed a different kind of virus they identified in the same mine as the miners’ cause of death in 2014). Such an occurrence would be evidence of a bat-borne virus similar to SARS-CoV-2 evolving to infect humans without any laboratory intervention.

(Science Magazine, March 2014)

Outside of absurdly involved and speculative claims involving the deceased miners' diagnostic samples being sent to the WIV and then used in undisclosed experiments, you would be hard-pressed to find an actual argument that specifically articulates why the discovery of this sample's changed name is suggestive of a laboratory leak. This could be, at least in part, because the mine represents a textbook example of a high-risk environment for zoonotic spillover.

"Coronavirus co-infection was detected in all six bat species [found in the mine], a phenomenon that fosters recombination and promotes the emergence of novel virus strains," Shi's team reported in 2016. "Our findings highlight the importance of bats as natural reservoirs of coronaviruses and the potentially zoonotic source of viral pathogens."

While it is entirely fair to ask why the sample's origin and history were not more clearly stated, theories seeking to make explicit links between the mine, the WIV, and COVID-19 — when actually articulated — make scientifically implausible arguments while ignoring the more obvious truth that this mine is a natural breeding ground for novel SARSr-CoVs and SARS-CoV2-related coronaviruses.

Whether the sample/virus is named Ra4991 or RaTG13, its central significance is that a virus that evolved naturally in bats is related, as a cousin, to SARS-CoV-2.

SARS-CoV-2's Genome Does Not Contain "Smoking Gun" Proof of Engineering

Many formulations of the lab leak hypothesis do not specifically invoke RaTG13 but instead focus on the alleged improbability of a virus acquiring the adaptations it possesses naturally. The features most commonly cited as proof of human intervention relate to the spikes of SARS-CoV-2. To attach to a cell, the SARS-CoV-2 spike uses a receptor binding domain (RBD) to stick to an enzyme, ACE2, found on human cells. This feature is similar to how SARS-CoV-1 infects humans, and its genetic sequence appears to be a close match for RBDs in pangolin coronaviruses.

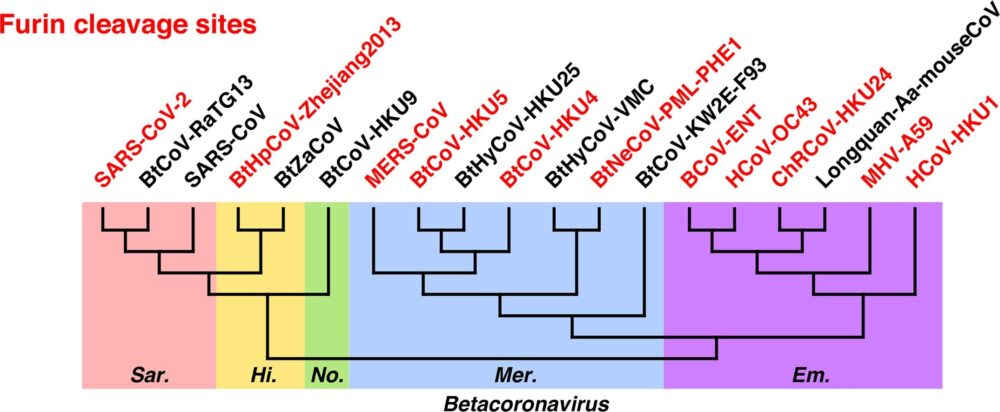

To enter a cell, a coronavirus spike protein also must be "cleaved" into two halves. Unlike SARS-CoV-1, SARS-CoV-2 can initiate the latter process using furin, a chemical found on a variety of human cells. For complex reasons, this adaptation allows the virus a faster and easier way to initiate cleaving in human lung tissue specifically. As respiratory infections spread easily through the air, such an adaptation makes SARS-CoV-2 much more transmissible than either SARS or MERS.

To lab leak advocates, such a fortuitous adaptation is allegedly unlikely to arise naturally. No other viruses in the group of viruses SARS-CoV-2 belong to have this adaptation, they argue, and such a fortuitous adaptation couldn't possibly come from mutations or recombination. Wade, for example, argued:

Of all known SARS-related beta-coronaviruses, only SARS2 possesses a furin cleavage site. All the other viruses have their S2 unit cleaved at a different site and by a different mechanism. How then did SARS2 acquire its furin cleavage site? Either the site evolved naturally, or it was inserted by researchers at the S1/S2 junction in a gain-of-function experiment.

This reasoning presents a misleadingly narrow view of coronavirus genetic diversity. While such furin cleavage sites are not present in the specific and likely under-sampled lineage of viruses that includes SARS, they are present all across the betacoronavirus family, including some that cause common colds in humans. Because this genetic feature occurs all across the coronavirus evolutionary tree and is not confined to one group, University of Utah virologist Stephen Goldstein told the scientific journal Nature, furin cleavage sites have likely evolved independently and naturally several times.

The furin cleavage site in SARS-CoV-2 arises thanks to a genetic sequence in the spike protein that contains something that has been dubbed a double CGG codon. (CGG is one of several genetic sequences that codes for the amino acid arginine.) It is, Wade argued, the least common method employed by coronaviruses to make arginine but a common way the human genome codes for it. On top of that, Wade states, CGG would be expected in a laboratory experiment, as the CGG codon is routinely used in such work.

The media granted this argument a great deal of support thanks to a quote from David Baltimore, a professor emeritus at the California Institute of Technology and a Nobel laureate. "When I first saw the furin cleavage site in the viral sequence, with its arginine codons, I said to my wife it was the smoking gun for the origin of the virus,” Baltimore said to Wade. “These features make a powerful challenge to the idea of a natural origin for SARS2.”

The idea presented by Wade is flawed, and Baltimore has since walked back his quote. The CGG arginine codon sequence appears in 3% of the full SARS-CoV-2's genome and 5% of SARS-CoV-1's genome. It is literally possible for such arginine sequences to appear naturally in these viruses. In an essay titled "When a Good Scientist Is the Wrong Source," MIT science writing professor Thomas Levenson declared that "Baltimore certainly is an authority, but his jurisdiction does not extend to all the complexity that nature displays."

Speaking to the journal Nature in June 2021, Baltimore clarified that "there are other possibilities and they need careful consideration, which is all I meant to be saying.” There is a great deal of distance between "smoking gun" proof of engineering and a conclusion that 'it's possible.' In other words, no "smoking gun" evidence of anything has been presented.

Further, the notion that those CGG-based sequences are de facto evidence of laboratory work has been contested by several scientists who point out that, in the cell lines commonly used for experiments at WIV and elsewhere, such sequences are selected against, making this specific cleavage site unlikely to be a result of a serial passage experiment gone wrong.

The final class of arguments, therefore, relies on a narrow view of both COVID-19 pathogenesis and zoonotic spillover to cast the natural origin hypothesis as more unlikely than reality dictates.

Lab Leak Advocates Present a Misleading Depiction of Natural Origin Hypotheses

Lab leak advocates, in weighing the likelihood of zoonotic spillover, paint the absence of several features that characterized the earlier SARS and MERS outbreaks as evidence of unnatural origins. Scientists working on both of those diseases, lab leak advocates hold, rapidly identified the intermediate species providing the link between bat and human, and therefore should have by now done so with SARS-CoV-2.

Wade, for example, argued that absence of an intermediate host "was surprising because … the intermediary host species of SARS1 was identified within four months of the epidemic’s outbreak, and the host of MERS within nine months. Yet some 15 months after the SARS2 pandemic began ... Chinese researchers had failed to find either the original bat population, or the intermediate species to which SARS2 might have jumped."

First, while it is true that the intermediate hosts of both earlier coronavirus pandemics were identified quickly, it took 14 years to find "the original bat population" likely responsible for the SARS pandemic, and no such population has yet been identified for MERS. Second, an intermediate host — if one is required to explain SARS-CoV-2's origins — is often only transiently infected before the virus takes hold in humans. There may be a limited window of time in which it is even possible to identify a possible intermediate host.

Finally, on that point, there is no actual requirement that an intermediate host exist in the first place. Bats can, in fact, infect humans without an intermediate species. Humans who live in regions close to populations of infected bats and have never directly interacted with bats or the caves they live in have been found to possess antibodies to bat coronaviruses. The existence of an intermediate host is not required to infect humans with bat coronaviruses, and the inability to locate one is not evidence of unnatural origins.

Other arguments against a natural origin imply that it is somehow rare for anyone besides a virology researcher to come into contact with bats or to enter a cave or mine that houses them. "Who else besides miners excavating bat guano comes into particularly close contact with bat coronaviruses?" Wade argued. "Coronavirus researchers do." This is an absurd argument. First, one does not need to enter a bat colony to come into contact with a bat. Second, bat guano is commonly harvested in southern China for its use as a fertilizer.

(The Huanan Market. Photo by Hector Retamal/AFP via Getty Images)

A final allegedly problematic fact about SARS-CoV-2 is the distance between regions containing bats and Wuhan. "If the SARS2 virus had first infected people living around the Yunnan caves, that would strongly support the idea that the virus had spilled over to people naturally. But this isn’t what happened, " Wade argued. "The pandemic broke out 1,500 kilometers away, in Wuhan." Baker, similarly, suggested it is suspicious that "the disease ... traveled from the bat reservoirs of Yunnan all the way to Wuhan, seven hours by train, without leaving any sick people behind and without infecting anyone along the way."

Proponents of this argument seem to feign ignorance about both how pandemics begin and how COVID-19 works while pretending that it is somehow unlikely for a human living in a rural part of southern China to pass through an important industrial city of 11 million people in the 21st century. Initial "index cases" representing a transfer from animal to human usually do not result in pandemic spread, and early spillover events likely would have evaded detection.

Further, COVID-19 transmission is an enigmatic process driven, we know now, by undetected infections. Many people infected with SARS-CoV-2 do not show symptoms, and an estimated 50% of the disease's transmission occurs through asymptomatic or presymptomatic cases. This fact is what stymied early efforts to contact-trace COVID-19 cases, making it seem as though COVID-19 cases with no known contact to anyone infected appeared out of nowhere.

To illustrate this, take COVID-19's emergence in the United States as an example. On Feb. 27, 2020, CNN reported that a "patient in California who has coronavirus didn't travel anywhere known to have the virus [and] wasn't exposed to anyone known to be infected." This alarming finding made international news, as it was the first case of "community transmission" in the United States confirmed by the CDC. In the absence of any other data, such a case would appear to have come out of nowhere, connected by no trail of infections and separated geographically from other known cases of COVID-19.

Allegations that the distance between southern China's bat population and Wuhan are suspicious is born from a similar absence of data. It is likely, according to epidemiological models, that human-to-human transmission of the virus began in "mid-October to mid-November" 2019. Unpublished government records described by the South China Morning Post in March 2020 indicate that the earliest documented case of COVID-19, retroactively identified once COVID-19 tests were designed, first presented severe symptoms on Nov. 17, 2019. The international community simply does not have the data to argue that SARS-CoV-2's arrival in Wuhan — if it came from elsewhere — occurred "without infecting anyone along the way."

Do any of these facts prove a natural origin? No. But arguments painting zoonotic origin as unlikely based on distance or lack of intermediate host mischaracterize what is known about the disease and limit, rhetorically, the conditions under which a natural origin might plausibly occur.

The Bottom Line

The People's Republic of China has done itself no favors when it comes to its commitment to transparency or building international trust. Front-line doctors themselves connected the dots of several cases of suspicious pneumonia due to the shared connection to an animal market — the Huanan market — and its obvious parallels to the SARS outbreak. When these doctors attempted to raise an alarm internally, they were silenced and punished by Wuhan's health authorities.

For example, Ai Fen, the director of Wuhan Central Hospital's emergency department, stated in an interview that went viral in China (despite being heavily censored by authorities) that "she was told by superiors ... that Wuhan’s health commission had issued a directive that medical workers were not to disclose anything about the virus, or the disease it caused, to avoid sparking a panic."

It is entirely fair to ask tough questions of China regarding both their coronavirus research and pandemic response. It is fair to demand access to data that could elucidate COVID-19's origins, including Chinese data on early cases of COVID-19 described in media reports and the full genomic sequences of the other unpublished SARS-related coronaviruses identified at the Mojiang mine.

But these legitimate concerns over data transparency, laboratory safety, and bioethics have repeatedly been presented alongside wildly speculative and scientifically confused arguments that lack any evidentiary merit. These speculative scenarios have been presented in media reports as evidence, even though they rely on overt scientific misrepresentations or falsehoods.

McNeil, for example, argues that we still have no definitive answers about where SARS-CoV-2 came from, but that "the Occam’s Razor argument — what’s the likeliest explanation, animal or lab? — keeps shifting in the direction of the latter."

McNeil's piece, however, includes as evidence the work of Yuri Deigin, whose argument rests on the false assertion that "CoV2 is … based on the ancestral bat strain RaTG13." It also cites the work of Milton Leitenberg, who conflates fecal swab samples with living viruses. And it relies on motivated reasoning of Nicholas Wade alleging the existence of "smoking gun" evidence for genetic manipulation. Stripped of these dubious arguments, the most prominent lab leak pieces have presented very little "evidence" that justifies such a shift in opinion.

McNeil concedes that "much of the debate comes down to this: Is Dr. Shi telling the whole truth? And even if she is, are all her similarly skilled colleagues in Wuhan?" This is indeed the central crux of the debate. To suggest that the speculative, underdeveloped, or scientifically confused "what-ifs" posed in a series of self-referential blog posts constitutes scientific evidence capable of contributing to that debate, however, is deeply misleading.