The latest installment of soccer's European Championship — still officially known as "Euro 2020" despite being postponed by a year due to the COVID-19 pandemic — began on June 11, 2021, with Italy's 3-0 win over Turkey.

The tournament heads into its opening weekend under the shadow of simmering tensions over "taking a knee," the anti-racist gesture popularized by former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick in 2016 and adopted as a pre-match ritual of solidarity by soccer players in England and Europe, as part of the wave of global protests that followed the murder of George Floyd, a Black man who died in May 2020, when a white former Minneapolis police officer kneeled on his neck for more than nine minutes.

In England's Premier League, the world's most-watched club soccer league, players from all teams took a knee before every game from the end of the 2019-20 season through the entire 2020-21 season, a period during which fans were almost entirely absent from stadiums.

However, with fans now returning to venues as various governments enact COVID-19 reopening plans, a new problem has emerged: vocal and disruptive opposition from some soccer supporters to taking the knee.

In England, in particular, the issue is approaching a crisis. Before the team's 1-0 win against Austria in a pre-tournament warmup game on June 3, sections of the home crowd at the Riverside stadium in Middlesborough booed as England's players and coaching staff took a knee. The team's widely respected manager Gareth Southgate said, "It's not something, on behalf of our black players, that I wanted to hear, because it feels as though it's a criticism of them."

Of the 26 members of England's Euro 2020 squad, 11 are of Caribbean or African heritage, including star players Marcus Rashford and Raheem Sterling, as well as teenagers Bukayo Saka and Jude Bellingham.

Southgate later vowed that his players and coaching staff were "more than ever, determined to take the knee through this tournament." The next day, some England supporters once again booed the gesture before another pre-tournament game against Romania in Middlesborough, setting the stage for an extraordinary stand-off between the English national team and some of its own supporters on the eve of a major tournament in which England is a genuine contender.

The controversy has been replicated, albeit with less intensity, in other European nations, and concerns remain that adverse reactions to the gesture, in some of the 11 host cities spread across the continent, could sour this summer's tournament. Scotland, for example, initially declared it would not be taking a knee before games, but reversed that decision in solidarity with the backlash faced by its English counterparts.

Wales has committed to making the gesture before its Euro 2020 fixtures, with Belgium and reigning world champions France reportedly joining in. However, most of the 24 competing nations have not taken a premeditated stance, and some have declared their clear opposition to it.

In Hungary, right-wing Prime Minister Victor Orban has lashed out at taking the knee as a "provocation," and in Budapest, which will host group stage and knockout games in Euro 2020, home supporters booed as Irish players took a knee before a pre-tournament warmup game on June 8.

While it's unlikely to lead to drastic consequences, such as teams withdrawing from games or the exclusion of fans from stadiums, taking a knee, and the reaction of fans across Europe to it, could be the defining controversy of this year's European Championships, which will have a global audience of hundreds of millions. It would not be the first time that a controversy or geopolitical conflict affected the tournament, which has been hosted every four years since 1960.

Here's our breakdown of four previous occasions when major controversies and political disputes played a part, sometimes decisively, in the showcase event of European soccer and one of the world's most widely viewed sporting events.

1960: Spain Boycotts the Soviets

Qualification for the inaugural tournament, then known as the "European Nations' Cup," began in 1958. A golden generation of Spanish footballers, including the great Alfredo Di Stéfano, eased past Poland, winning 7-2 on aggregate over two legs played in Chorzów and Madrid in 1959, and qualifying them for the quarterfinals against the Soviet Union.

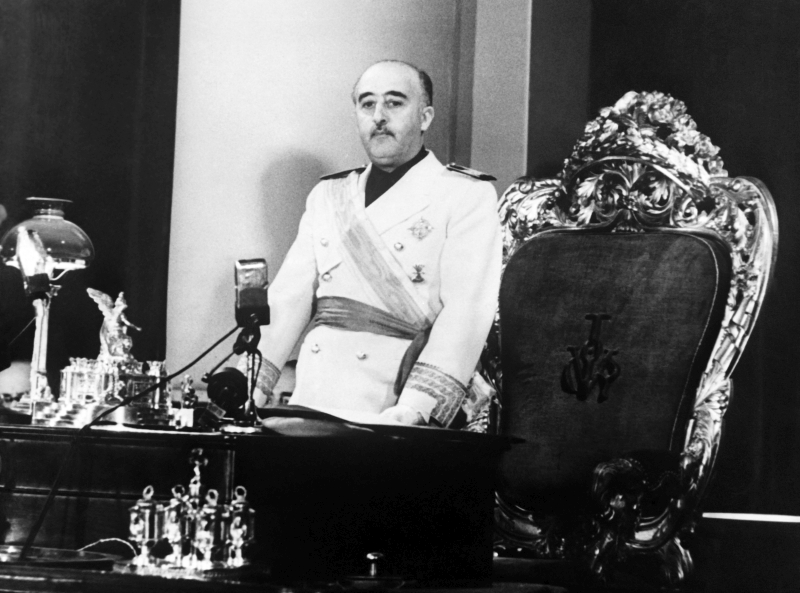

However, just days before the first leg was scheduled to played in May 1960, Spain abruptly withdrew. According to reports, Di Stefano demanded to know why and was told by Spain's chief football administrator, Alfonso de la Fuente Chaos: "Orders from above... Franco said so."

Spain's military dictator was reportedly influenced by the Soviet treatment of Spanish World War II veterans and disgusted by the prospect of the Soviet flag being raised and anthem being sung in Madrid. Whatever the precise reasons, his decision to boycott the quarterfinal turned out to be a consequential one.

The Soviets, given a walkover, beat Czechoslovakia in the semifinal, and overcame Yugoslavia in the final, becoming the inaugural champions of Europe.

1980: England's Hooligans Risk Expulsion

Crowd violence and hooliganism was a major problem in English and European soccer during the 1970s and 1980s, and one particularly egregious episode in the 1980 Euros prompted a significant backlash against the English and even risked their participation in the tournament.

England, complete with star players like Kevin Keegan, Ray Wilkins, and Trevor Brooking, was widely expected to defeat Belgium in their group stage game in Turin, Italy, on June 12.

Wilkins put England in front after 26 minutes, but Belgium equalized just three minutes later, prompting a riot by English supporters in the stadium. The game ended in a draw, and England's subsequent defeat to Italy saw them exit the competition at the group stage, but the violence seen in the Belgium game prompted a fierce backlash, as The Guardian described in 2020:

[England manager Ron] Greenwood was furious with the fans. “I am proud of my profession, but when things like this happen, I am ashamed of football. They are idiots and we don’t want anything to do with them. I wish they would all be put in a boat and dropped into the ocean.” England skipper Keegan was just as scathing: “I know 95% of our followers are great, but the rest are just drunks.” Frank McGhee continued the theme in the Mirror, writing: “English soccer’s band of travelling hooligans once again dragged their game and their country into the depths of disgrace here last night.”

Prime minister Margaret Thatcher, who was in Venice for the Common Market Summit, added to the increasing volume of dissenting voices: “The behaviour of some British supporters in Turin was disgraceful. When they come here, they are ambassadors and should show the best of Britain. It was a very dark day.”

Uefa arranged an emergency meeting to discuss the violent scenes, with a points deduction or even expulsion from the tournament mooted as possible punishments. The resulting £8,000 fine was seen as lenient, with FA chairman Harold Thompson admitting: “It could have been a lot more serious for us. But it is a pity we have to pay for the actions of those sewer rats.”

1992: The Danish Fairy Tale

Denmark failed to qualify for Euro '92 through the conventional route. In Group 4 of the qualifiers, the team came second, finishing one point behind Yugoslavia. However, on May 30, 1992, less than two weeks before the tournament was scheduled to begin, the U.N. Security Council passed Resolution 757, which imposed sweeping sanctions and embargoes against Yugoslavia in response to the civil war and conflicts that had erupted in the region.

As a result, Yugoslavia was disqualified from the tournament and Denmark, some of whose players were already planning their summer vacations, were called up as the eighth team in the competition. With the exception of the 1980 Olympics boycott, arguably no geopolitical intervention has proven more consequential to a sporting event.

Rank outsider Denmark, led by Brian Laudrup, John Jensen, Henrik Larsen, and goalkeeper Peter Schmeichel, narrowly qualified for the semifinals, then turned in two truly extraordinary performances.

In the semifinals, Denmark beat reigning European champions the Netherlands on penalties. In the final, against all odds, it defeated reigning world champions Germany 2-0 to wrap up the fairy tale and be crowned the European champion.

2000: England's Hooligans Risk Expulsion (Again)

Twenty years on from the Turin riot that marred England's participation in the 1980 European Championships, hooliganism reared its head once again, this time in Belgium. In its first game, England had managed to squander an early two-goal lead against Portugal and lost 3-2. This left tournament hopes dangling by a thread before England's second group game against traditional rivals Germany.

English fans rioted before the fixture against Germany, with police in Brussels and Charleroi arresting no fewer than 137 English nationals for vandalism, assault, and public order offenses. The BBC reported at the time that Belgian police fired tear gas into a bar in Brussels after English fans barricaded themselves inside, throwing chairs and bottles at police. In Charleroi, business owners closed up early as English fans threw tables and chairs and became embroiled in fighting with German supporters and some of the city's local Turkish community.

Over the course of the weekend of June 16-18, Belgian police arrested 824 fans in total, most of them reportedly English.

In the aftermath of the violence, top administrators from UEFA, the sport's European governing body, warned that England could be expelled from the tournament altogether. At a press conference held after an emergency UEFA board meeting, CEO Gerhard Aigner said, "UEFA will have to determine whether the presence of the English team in the tournament should be maintained should there be a repetition of similar incidents."

For his part, UEFA President Lennart Johansson vowed: "We are serious. This cannot go on. It will kill football."

The controversy became overtly political when tournament director Alain Courtois lashed out at the government of Prime Minister Tony Blair for purportedly failing to do enough to prevent known criminals, including members of English far-right and neo-Nazi groups, from travelling to host nations Belgium and the Netherlands. The U.K. government rejected those charges, while Blair himself remarked: "Hopefully this threat will bring to their senses anyone tempted to continue the mindless thuggery that has brought such shame to the country."

England ended up beating Germany 1-0, but suffered an ignominious early exit from the tournament after losing 3-2 to Romania in their final group game.