For Rayshard Brooks, fighting misconceptions about his past had become part of his daily life. Before a white Atlanta police officer fatally shot him in a fast-food restaurant parking lot on June 12, 2020, Brooks, who is Black, said he worked hard to challenge people's beliefs about what it means to have a criminal record in America.

"If you do some things that's wrong, you pay your debts to society," he said in a February 2020 video interview. "I just feel like some of the system could, you know, look at us as individuals — we do have lives ... [and] not just do us as if we are animals."

Now, as two police officers face criminal charges in his killing and his name becomes part of protest chants against racism in policing nationwide, some vocal corners of the Internet say his past arrests and incarcerations are crucial for understanding — and justifying — why police killed him.

Those critics include Peggy Hubbard, a former police officer who gained viral fame among American conservatives for her criticism of the Black Lives Matter movement (and for being a Republican candidate in Illinois' Senate 2020 race). In Facebook videos that have been viewed hundreds of thousands of times since Brooks' killing, Hubbard said Brooks "caused his own death" by resisting arrest and people should not judge the actions of the Atlanta police officers before first considering Brooks' criminal record.

Mr. Brooks has a record for child endangerment. Mr. Brooks has been in and out of prison, and I’m sorry for his family, and I’m sorry that he lost his life. But it does not give us the right as Black Americans that every time we get mad at the police, we have to loot, we have to burn, and we have to riot. Not everyone is deserving of our outrage. He is not deserving of our outrage.

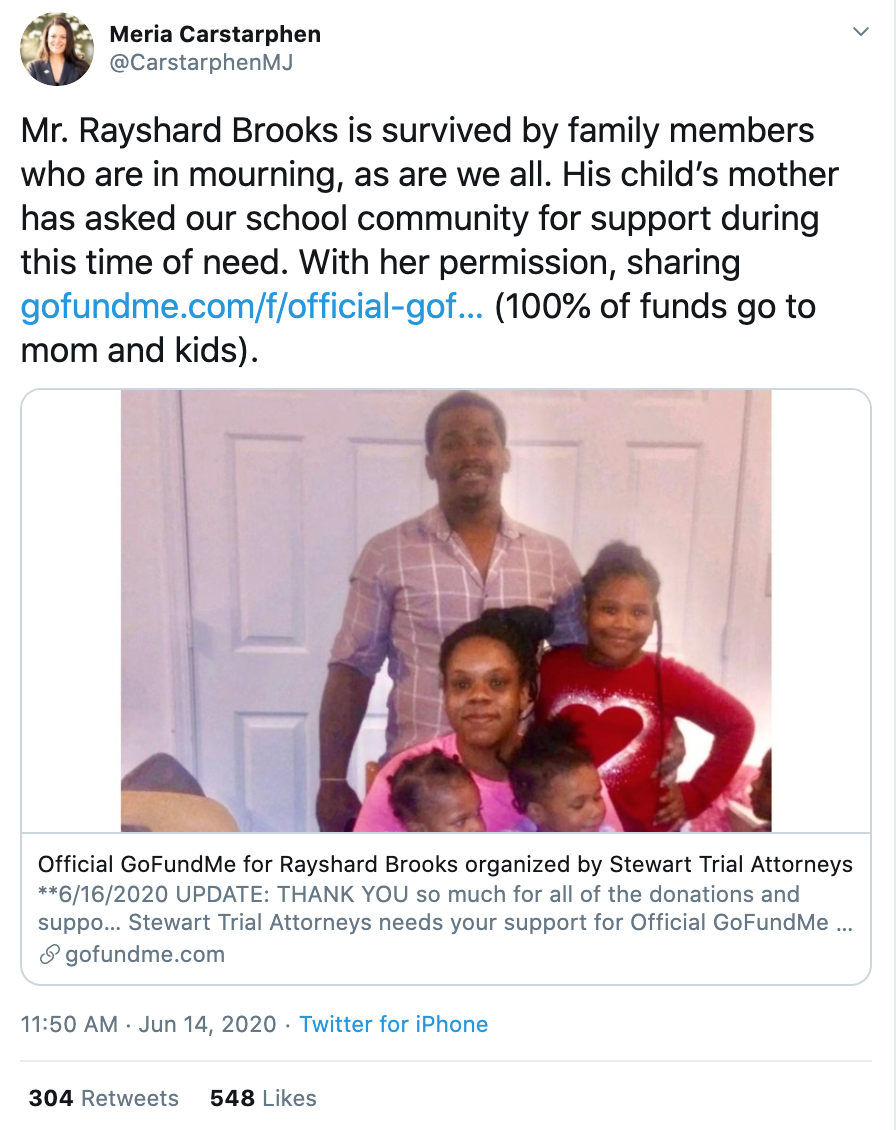

At the request of Snopes' readers, we investigated the source of these claims and others. In doing so, we analyzed hundreds of documents that included court filings, witness statements, and crime-scene photos obtained via the Georgia Public Records Act, as well as contacted law enforcement and corrections officials. The records piece together a complicated life, involving both fatherhood — Brooks left behind three young daughters and one teenage stepson — and criminal sentences for vehicle theft and battery violence against a family member, among other crimes.

What follows is what we know about Brooks' interactions with police, mostly near an apartment complex where he had lived in the Atlanta suburbs. We should note at the outset the following parties did not respond to our requests for comment on the findings of our investigation: Hubbard; the attorney for Brooks' family, L. Chris Stewart; the attorney (Lance LoRusso) who is representing the former officer who shot and killed Brooks; and public information officers for the Atlanta Police Department.

Many Online Claims About Brooks Are False, or an Exaggeration of the Truth

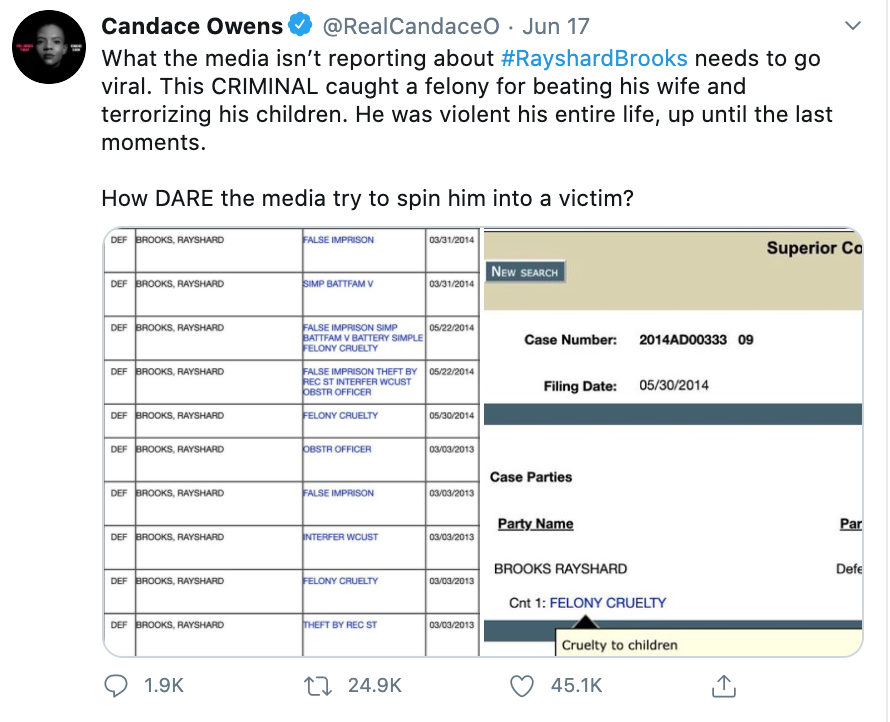

Hubbard was not the only person who claimed — without proof — that Brooks had abused his children. Without citing substantial evidence, conservative blogs and social media accounts shared memes (like the one displayed below) and sensationalized tabloid stories in the days after Brooks' death, seemingly as part of an effort to deny him martyrdom during an international reckoning over racism and police brutality after the death of George Floyd, a Black man who died in police custody in Minneapolis in May 2020.

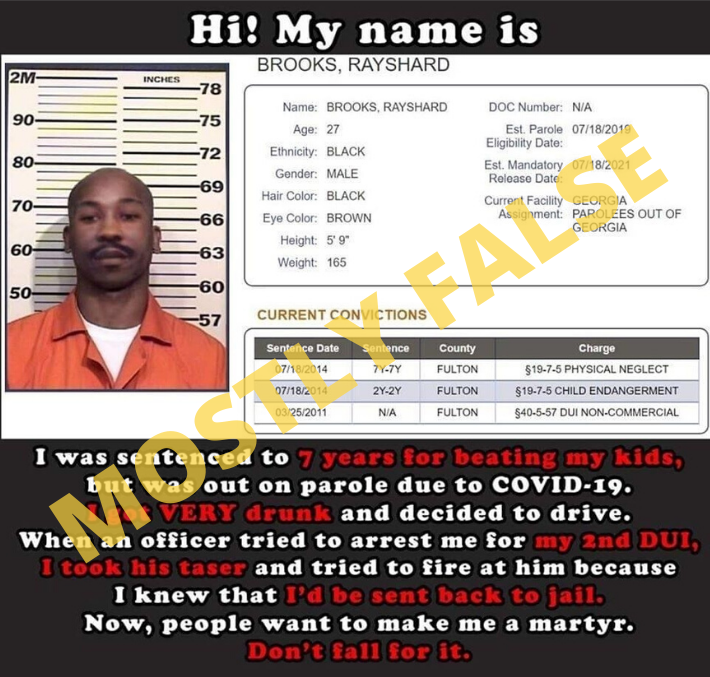

Upon our analysis of such posts, we determined the most popular rumor to be this: that Brooks had been sentenced to prison for seven years for physically abusing his children, and that he was on parole due to the COVID-19 pandemic when police questioned him about driving under the influence in a Wendy's restaurant parking lot before his death. In addition, the posts claimed Brooks had been arrested previously on DUI charges:

But the above-displayed post, in particular, is rooted in falsehoods. The alleged convictions — that Brooks was convicted in Fulton County on charges of physical neglect and child endangerment in 2014, as well as DUI in 2011 — are completely made up, according to a review of county records by the clerk's office. (Shatavia Scott, an office administrator, confirmed with us via email there were no such charges filed against Brooks in Fulton County.)

In our review of records outside Fulton County, however, we deemed the most serious allegation — that Brooks had been sentenced to prison for "beating his kids" — an exaggeration of cases of family violence and vehicle theft involving Brooks; however, Georgia laws governing public records and the privacy of victims of family violence prevent us from knowing exactly what had happened.

Additionally, our analysis of Brooks' criminal record found no evidence to suggest he had been arrested on DUI charges before his fatal encounter with police.

In regards to the claim that Brooks was "VERY drunk and decided to drive" to the Wendy's, Brooks had taken a breath test for alcohol that showed a digital readout of 0.108 before he was killed, according to footage from the officer's body-worn cameras. That reading is significantly higher than the 0.08% blood alcohol content considered too intoxicated to drive in Georgia, which means — pending the accuracy of the breath test — it would be accurate to say Brooks had alcohol in his system and possibly was drunk.

For scientific proof of Brooks' blood alcohol level, however, we requested records from the Fulton County Medical Examiner's Office, which conducted an autopsy of Brooks' body two days after his death. The office said it had submitted a blood sample to the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI), which was heading the investigation into Brooks' killing, and that that agency had yet to complete a toxicologic analysis. (In other words, the officer's breath test was the only available evidence as of this report to determine Brooks' intoxication level.)

Also, we should note here that Brooks told the Atlanta officers before they shot and killed him that he had been dropped off at the Wendy's and didn't drive there.

Lastly, Brooks was not on parole when he died, per the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles, which is the state-authorized panel that reviews inmates' behavior in prison and can grant them an early release. It's also false to assert the COVID-19 pandemic had anything to do with Brooks' incarceration history. Steve Hayes, a spokesman for the board, said in an email:

"The social media reports are wrong. The individual was not released on parole by the board as a result of COVID-19 or anything to do with COVID-19. The individual was not on parole."

Brooks, however, was on probation — which, unlike parole, is issued by a court and part of an offender's initial sentence — and was under the supervision of a probation officer when officers suspected him of driving under the influence of alcohol at the Atlanta Wendy's before killing him.

(Note: When someone is convicted of a crime, such as DUI, while they are already on probation for previous crimes, the defendant's record gets marked with a "substantive violation" — which can lead to a longer probation sentence, prison time, or fines for the defendant.)

Brooks Was Never Arrested on Suspicion of Child Abuse

Here, we lay out why, and under what circumstances, Brooks was on probation at the time of his death, as well as relevant details about his previous run-ins with law enforcement.

Brooks' first experience of trying to prove his innocence to police officers and prosecutors was at age 14, when he was arrested in Atlanta's Fulton County on suspicion of shooting and wounding a man during a carjacking, as well as stealing another vehicle and robbing a different person at gunpoint at a bus stop. Investigators believed one person had committed all of the crimes, though it's not made clear in court documents how, or why, they came to that conclusion.

Brooks was tried as an adult in Fulton Superior Court, not juvenile court, and pleaded not guilty. Brooks' attorney alleged the charges were erroneously based "solely on the alleged identification of the accused by the alleged victims, with no physical or other tangible evidence [such as DNA, fingerprints, blood samples, etc.]" connecting Brooks to the crimes. Furthermore, the attorney said the mugshot photos used by police to identify Brooks as the suspect in the carjacking and armed robbery were unfair, and that prosecutors wrongly lumped several crimes into one case, among other problems with the police investigation.

In the end, Brooks spent more than two years at Atlanta's Metro Regional Youth Detention Center, where an attorney at one point told a judge he had received an "excellent" report card by supervisors and teachers.

In 2010, soon after Brooks' release from juvenile detention, Brooks was questioned by police about an armed robbery that had occurred near his home in an apartment complex in Jonesboro, which is about 20 miles south of Atlanta. Initially, Brooks told officers that he didn't know anything about the crime. But in a second retelling of events, he told those officers that, on a walk outside with his son, he had a brief exchange with the person who was robbed before the crime happened, as well as one of the suspected robbers, and helped police's investigation soon after the incident.

Other than those non-incriminating details, law enforcement found no evidence to connect Brooks to the armed robbery but arrested him on suspicion of telling a lie to police officers when he denied knowing anything about the robbery. The report stated:

"The offender then stated that the reason he had made the false statements about the robbery was because he had just got out of jail for armed robbery and didn’t want to get into any more trouble."

He was sentenced to one year of probation for making a false statement to a police officer, though court records show he violated the terms of that probation agreement and others.

Beginning in spring 2011, Brooks, then 18, was arrested in connection with offenses that seemed to have been largely misinterpreted after his death and formed the basis of exaggerated claims that he had abused his children. On March 16, 2011, for instance, Clayton County prosecutors sentenced him to one year probation and fined him $300 for allegedly causing physical bodily harm to a member of his family, though it's unclear whom.

Due to Georgia statutes that aim to protect the privacy of victims of such crimes, we were not granted access to records outlining the specifics of that case of family violence to explain why, or under what circumstances, Brooks was involved. We also don't know who contacted authorities to begin with, or the severity of the victim's injuries. We know, however, the offenses on Brooks' criminal record and for which he was charged were: battery family violence, battery, simple battery family violence, and simple battery. (Only Brooks or the unidentified relative could legally obtain the records under the state's open records laws, per Michelle Roberts, a police records custodian for the Clayton County Police Department.)

Brooks next faced police interrogation in January 2012, when armed police officers surrounded a vehicle that he was inside with another man. Apparently, police believed that man was the suspect in a shooting hours earlier. Brooks told the officers, per the police report:

... that he doesn’t really know [the other man] and that he just buys marijuana from [him]. Less than an ounce of marijuana and two checkbooks … were found inside the pocket [of] Brooks who stated that he just purchased the marijuana from [the other man and he] threatened to harm him if he doesn’t place the checks in his pocket due to the police coming.

He was arrested and charged with having weed and being in the presence of a gun — the officers found one in the vehicle's console — during a crime, though it’s unclear based on the records provided to Snopes if that firearm was connected to the alleged shooting. A judge sentenced him to more than one year of jail, with an early release if he met certain conditions.

In 2013, Brooks was arrested again for allegations that also fueled online rumors of abuse. According to a January police record, an officer found Brooks, 19, and Miller, 24, sleeping in a car behind a house that someone had reported to police as seeming suspicious. When the officer knocked on the car window, the officer said the following events transpired:

The male woke up and immediately started the vehicle. I opened the driver door and ordered the driver to turn the car off. The male then put the car in reverse and started to drive away from the house. From the position I was in the open driver door hit me and started to push me under the vehicle. I then let go of the driver and the vehicle and rolled away from the vehicle to avoid injuries. While this was going on, I could hear a baby begin to cry.

The family hastily drove away and hit a tree while doing so, the report stated. Then, a few hours later, Clayton County police said they found an unoccupied car that matched the description of the car in the above-detailed event, and it was registered as stolen.

Three months later, police accused Brooks of committing the following crimes during what started as the 911 report of a suspicious vehicle mentioned above: theft by receiving stolen property, interference with police custody, false imprisonment, obstructing an officer, and cruelty to children. The latter offense includes any time children witness severe crimes or family violence, which is what seemed to have happened (based on available records) in Brooks' case. He pleaded guilty in August 2014 and was sentenced to one year of prison and more than six years of probation.

In fall 2015 and spring 2016, Brooks was out of jail but arrested several times on suspicion of theft or credit card theft, offenses that violated the terms of probation in his aforementioned cases. He was sent back to prison for one year, fined $2,000, and issued more years of probation — sentences that surpassed the date of his death.

All of that said, in reference to online claims against him about family violence, it is accurate to state that Brooks at one point was charged with battery family violence, and one criminal allegation against him involved one or more child. But there's no evidence to prove he physically harmed the children, and Brooks never faced allegations of child abuse, which is often the category of offense when people "beat" children.

We Don't Know If Cops Knew of Brooks' Criminal Record Before Killing Him

Shortly after 10:30 p.m. on June 12, 2020, someone called Atlanta Police Department (APD) to the fast-food restaurant to check on a man who had fallen asleep in his car while parked in the drive-thru line, forcing other customers to drive around him to order food, according to the GBI.

A 26-year-old officer named Devin Brosnan — who had been with the force for less than two years — approached the vehicle and found Brooks sleeping in the driver’s seat, according to footage from Brosnan’s body-worn camera. About seven minutes later, Brosnan contacted dispatch and asked for an officer who is authorized to conduct DUI investigations to come to the Wendy's. Officer Garrett Rolfe took the call.

Rolfe, a 27-year-old who had been with APD since 2013 (and had multiple complaints filed against him, including from a Black man who accused Rolfe and another officer of harassing and citing him because of his race) conducted a sobriety test in the parking lot. Then, after roughly 30 minutes of questioning Brooks, Rolfe told Brooks he "had too much drink to be driving" and asked him to put his hands behind his back.

Less than one minute after Rolfe's attempt to handcuff Brooks, he was struck by two gunshots to the back.

According to cellphone videos from bystanders in the Wendy’s parking lot and dashboard cameras in officers' squad cars, Brooks was shot after he resisted handcuffs and attempts by officers to restrain him. While wrestling with the officers, Brooks grabbed Brosnan's Taser — which is a non-lethal weapon police officers use to shoot electrifying darts at people whom they deem threatening — and punched Rolfe, who then fired a Taser at Brooks as he tried to run away from them, according to the videos.

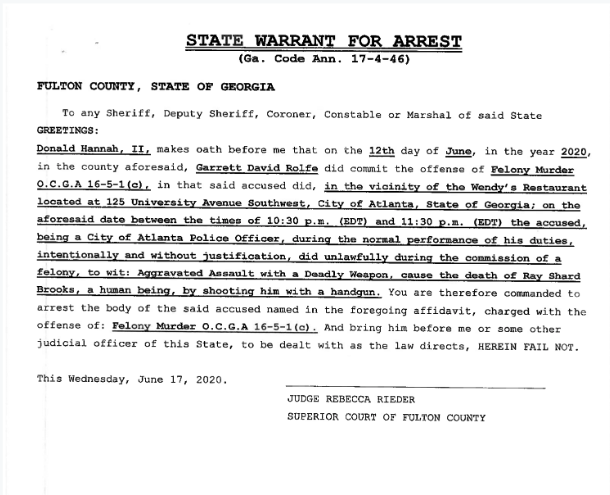

Wendy’s surveillance footage captured Rolfe chasing Brooks, who was running and turned around once to fire the Taser in the officer’s direction. Then, the video shows Rolfe dropping his Taser, grabbing his handgun, and firing three times. (According to Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard, who has charged Rolfe with felony murder in Brooks' death, Rolfe declared, "I got him," after striking Brooks with bullets.)

Wendy’s surveillance footage captured Rolfe chasing Brooks, who was running and turned around once to fire the Taser in the officer’s direction. Then, the video shows Rolfe dropping his Taser, grabbing his handgun, and firing three times. (According to Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard, who has charged Rolfe with felony murder in Brooks' death, Rolfe declared, "I got him," after striking Brooks with bullets.)

In regards to whether the APD officers knew of Brooks' criminal history before or during the call, Brosnan was seen in the body-cam footage using his squad car computer several times in the Wendy's parking lot. Although we can't tell from the footage what he was looking at or searching for, the computer made several audible sounds while Brosnan conducted a search of some kind after asking Brooks to pull out of the drive-thru line and again later in the police call.

If that computer activity had revealed Brooks' criminal record, it is unknown whether that information at all influenced how he or Rolfe acted, consciously or subconsciously. APD spokespeople did not respond to Snopes' questions about the officers' knowledge of Brooks' criminal history before or during the 911 call that led to his death, and whether officers in general adjust their actions, or how they approach suspects based on the past arrests or incarcerations of people involved.

Speaking to the Toledo Blade newspaper, Brooks' father, Larry Barbine, said he thought the officers "pre-judged" his son not only by the color of his skin, but also because of his past arrests. "They thought they knew who he was before they stopped him," Barbine said. "They didn’t know him."

Atlanta Officials Don't Believe Officers' Deadly Use of Force Was Justified

On June 13, the day after Brooks' death, APD Chief Erika Shields voluntarily stepped down from her position leading the force. Rolfe was terminated, and Brosnan was placed on administrative leave. Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms said publicly that she did not believe the officers' use of deadly force was justified. She told reporters:

"While there may be debate as to whether this was an appropriate use of deadly force, I firmly believe that there is a clear distinction between what you can do and what you should do."

Five days later, Howard announced 10 criminal charges against Rolfe — in addition to the charge of felony murder, which carries life in prison or the death penalty, if prosecutors decide to seek it — and three charges against Brosnan, including aggravated assault and violations of oath. Alleging that Brooks at no point posed a threat to the officers, the prosecutor said Rolfe and Brosnan did not notify Brooks that they were arresting him on suspicion of DUI before trying to handcuff him, which broke APD policy, and that Brooks was calm and cordial with them.

Lawyers for Rolfe disagree with the claim that Brooks did not pose a threat, citing the video footage. Both Brosnan and Rolfe contend their actions in the Wendy's parking lot were lawful and in line with APD policy,

Rolfe and Brosnan surrendered to authorities the day after Howard announced the charges, and Brosnan was released from custody on signature bond while Rolfe was held at the Fulton County Jail without bond, as of this report. (Due to Georgia's delay in adjudicating cases because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Howard said a grand jury is not likely to review the case for an indictment until January or February 2021.)

Meanwhile, the city of Atlanta erupted with chaotic demonstrations of people who considered Brooks' killing yet another senseless murder of a Black man by white officers, while some police officers protested the prosecutor's decision to criminally charge their colleagues. Vince Champion, southeast regional director for the city's police union, told the The Associated Press that officers were walking off their shifts or not responding to calls because they felt "abandoned, betrayed, used in a political game."

Two Sides (Or More) to Every Story

To the people who knew and loved Brooks, he was a loving family man who worked hard to overcome the challenges that come with having a criminal record, and ultimately wanted to make sure his three daughters, aged 1, 2, and 8, and a 13-year-old stepson, were happy.

"They got him wrapped around their fingers," said Miller, his wife of eight years, after his death. She said they had built a relationship together that "no one could break."

He spent most of his life living in Georgia, where he was born. His father, of Toledo, Ohio, whom Brooks hadn't grown up with, told the Toledo Blade that Brooks spent 2019 visiting him and Brooks' half-sister, and that they spent the year catching up on lost time with activities such as fishing and sledding. Brooks told the Ohio relatives that he eventually wanted to settle down in Toledo with his family, who remained in the Atlanta area.

In many ways, Brooks tried hard to overcome the challenges of probation and make a livable income to help support his family, according to the people who knew him. During his time in Toledo, for example, he worked a construction job, where his boss, Ambrea Mikolajczyk, said he worked hard — he was the first person to arrive to work in the morning and the last person to leave — and appeared to be doing everything possible to improve his life after incarceration. At Brooks' funeral on June 23, she said:

Ray had overcome his circumstances. ...The justice system and systemic racism that exists made it fairly impossible for him to try to live a prosperous life well after he had paid his debt — the system kept drawing him in, grabbing ahold of him like quicksand.

She said he would commute by bike, help anyone who needed it, and had an infectious laugh and a smile that would "encapsulate his entire face."

He was well-liked by people in his Atlanta social circle, too. He worked at a Mexican restaurant there, and was described by a family friend in the city as "an outstanding person" who was outgoing, easy-going and "rarely in any trouble at all." The city's public school district promoted an online fundraiser to help the family with money after his death.

In February 2020, roughly one month after authorities caught Brooks violating the terms of his probation by taking the trip to Ohio to visit family, he responded to a Craigslist ad from a company that advocates for former prison inmates and researches recidivism. The ad was seeking to hear from people who were currently on probation or parole to learn what societal barriers prevent them access to opportunities like everyone else.

In a 41-minute recorded interview, Brooks talked about how potential employers had judged his past, and despite his best effort to work hard and provide for his family, the mounting court costs and stigma around what it means to have an ankle monitor during probation, for example, had put a lot of pressure on him.

"[There's] a lot of things that we lose by being incarcerated," he said. "We have to go back and fix things with our kids and gain that trust back with being away. My older daughter says, 'Dad — hey, I love you so much, but where have you been?"

Brooks said he would have benefited from some type of mentorship program to help him stay out of the legal system for good, someone who could help him understand the terms of his probation sentence so he would not violate them, for example. Brooks said in the interview:

Ya’ll took the time to lock me up and, you know didn’t care — I was sitting in there, but yet I’m out now and I have to try to fend for myself when I’ve been taken away from society. ... Once you get in there, you’re in debt — just in debt. For one individual to try to deal with all of these things at one point in time is just impossible. ...

A lot of things have just caused me to be behind, but here I am, I'm trying. I'm not the type of person to give up, and I'm going to keep trying until I make it to where I want to be.

Why People Draw Attention to Criminal Histories of Black Men Who Die in Police Custody

For decades, corners of the internet and journalists have focused on the criminal records of non-white people killed by authorities, no matter the relevancy of those records.

Based on Snopes' analysis of who is — and who isn’t — drawing focus to the past arrests and incarcerations of victims of police violence in 2020, the most popular posts are by firebrand conservatives, such as Hubbard, or conservative commentator Candace Owens, who made several accusations about George Floyd’s criminal past in a June 2020 video viewed almost 7 million times. Owens also drew attention to Brooks' criminal history after his death.

Their videos and posts often get shared by people who believe politicians or news reporters are purposefully omitting details about a subject's past unlawful behavior as part of a nefarious scheme to divide Americans, and that any claims of racism on the part of American officers are unfounded and feed into that polarizing effort.

Advocates for police reform, however, say the public narrative around police killings should not include the criminal histories of the deceased because they are unnecessary and distract people from the most important issue at the center of these incidents: Officers too often resort to violence when dealing with citizens, especially if they are Black, indigenous, or people of color.

By shifting the discourse away from officers' actions and onto the criminal background of the deceased, people can subscribe to the "he had it coming" trope so they don't have to feel sorry for the victim of police brutality, and can deny an officers' responsibility for their actions, said Richard Reddick, an associate dean at the University of Texas at Austin and researcher of systemic racism against Black Americans. He told us via email after Brooks' death:

In the Brooks example, it again illustrates the problematic assignment of responsibility away from the officers who shot Brooks in the back, twice. It’s all the more chilling to see the police officers talking with Brooks before the shooting, suggesting that there was a possibility of a peaceful outcome — and the fact they had copious information to find Brooks if they were not able to bring him into custody (if that was even necessary).

Among those who also criticized the intentions of people who called attention to Brooks' criminal history was late-night talk show host Trevor Noah. In a June 16, video, he said while the specific reasons people point in their rationale for why victims of police violence were at fault vary on a case-by-cases basis, all cases have one common variable: All victims were Black.

For people like Hubbard who said Brooks was rightfully shot and killed because he was combative with officers, Noah said:

People always say the same thing. They go, ‘Well, you know, if you didn’t do that, then you would still be alive.’ They say this shit all of the time. ‘If you didn’t do that.’ But the truth is, the ‘ifs’ keep on changing. …‘If you didn’t resist arrest, you would still be alive.’ Or, ‘If you didn’t run away from the cops, you would still be alive.’

‘Well, if you didn’t have a toy gun and were 12 years old in the middle of a park [in reference to Tamir Rice, who was shot and killed by a police officer in 2014], then you would have still been alive.’ ‘If you weren’t wearing a hoodie, you would have still been alive [referring to Trayvon Martin].’ …‘If you weren’t sleeping in your bed as a Black woman [like Breonna Taylor before she was killed by cops in March 2020], you would have still been alive.’ There’s one common thread beyond all the ‘ifs’ — ‘If you weren’t Black, maybe you’d still be alive.'