In late November 2017, President Donald Trump retweeted three videos posted by a leader of the far-right anti-Muslim hate group Britain First, a group known for sharing misinformation. The videos purportedly showed Muslims committing various acts of violence:

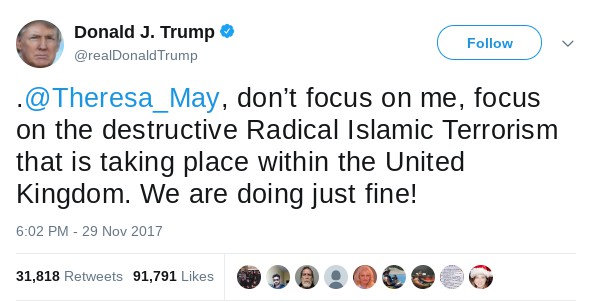

Although Trump did not offer his own comments when he first promoted the content, the next day, after British Prime Minister Theresa May said that "retweeting from Britain First was the wrong thing to do," Trump seemed to insinuate that all three of these videos were taken in the United Kingdom:

None of these videos were taken in the United Kingdom.

We previously addressed the footage that was shared with the caption "Muslim migrant beats up Dutch boy on crutches!" and found that the attacker not a migrant, and that his religion is unknown. You can read more about that video here.

The other two videos Trump tweeted are sorely lacking context.

For example, the video captioned "Islamist mob pushes teenage boy off roof and beats him to death!" was taken in Egypt in July 2013 during a series of violent protests that consumed the country after President Mohamed Morsi was ousted from office. The Los Angeles Times reported that 17 people were killed during the riots, including 17-year-old Hamada Badr who was thrown off the roof of a building by supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood:

As Muslim Brotherhood supporters rained stones and birdshot on demonstrators huddled at the opposite end of a busy street, Hamada Badr raced to the roof of a six-story apartment block to get a better view.

Some said 17-year-old Hamada and three teenage friends lobbed rocks at the pro-Brotherhood mob below. His friends denied this. But there is little dispute about what happened next.

Several Islamists chased after them, reached the roof and, to the horror of onlookers, threw three of the teens off the building in quick succession. Two fell 20 feet from a water tower to the main roof below and survived with injuries. A third escaped by clambering down a water pipe along the side of the building. But Hamada plummeted all the way to the ground, dying of severe internal bleeding at a hospital shortly afterward, friends said.

At least 17 people were killed Friday in Alexandria, Egypt's second-largest city, the highest reported death toll in a day of fiery protests nationwide against the military's removal of the controversial Islamist president, Mohamed Morsi. But it is the grisly circumstances of Hamada's death that have most stunned residents of this crumbling metropolis on the Mediterranean, prompting even onetime Morsi supporters to wonder whether the Muslim Brotherhood can ever regain political legitimacy.

This video was taken at the peak of civil unrest in 2013 Egypt. The tweet also makes no mention of the harsh consequences that the perpetrators faced following this teenager's death. More than 700 people who partook in the violence following Morsi's removal were sentenced to the death, including Mahmoud Ramadan, who was involved in the killing of Hamada. The Guardian reported:

An Egyptian man has been executed for pushing a teenager from a building, the first time that Egypt has enacted any of the death sentences given to hundreds of people accused of taking part in the unrest that followed the removal of Mohamed Morsi as president in 2013.

Mahmoud Ramadan was hanged for his role in the murder of a young Morsi critic in July 2013 during clashes between Morsi’s supporters and opponents. More than 50 others have been jail for more than 15 months for their alleged involvement in the same case.

At least 720 alleged Morsi supporters have been sentenced to death for their claimed role in Islamist-led violence in 2013, including the head of Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood, Mohamed Badie. But most of their sentences have yet to be enacted or have been quashed on appeal and sent to retrial.

The final video, captioned "Muslim Destroys Statue of a Virgin Mary" is also real — but it shows religious extremists who are members of the Islamic State, a militant organization that primarily terrorizes other Muslims.

This video has been circulating since at least October 2013 and purportedly shows a radical cleric named Omar Raghba smashing a statue shortly after members of IS raided homes in the Syrian village of Yakubiya. This statue was reportedly taken from the home of a Christian man killed by the IS militants:

Upon arrival, Wahhabi cleric Omar Gharba carried the statue of the Virgin Mary after it was taken over by militants from the "Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant" (ISIL) and broke it by throwing it on the ground. He stated that he and his fellow Wahhabis won't tolerate any form of worship except strict Wahhabism of Saudi Arabia.

"God willing, Only God will be worshipped in the land of the Levant," the terrorist who destroyed the statue said, noting that "no other idol will be worshiped after these days . We won't accept but the religion of Allah and the Sunnah of our Prophet Mohammed bin Abdullah."

Contrary to the actions of this radical cleric, Mary is actually a revered figure for most Muslims:

Mary, the Mother of Jesus, holds a very special position in Islam, and God proclaims her to be the best woman amongst all humanity, whom He chose above all other women due to her piety and devotion.

“And (mention) when the angels said, ‘O Mary! Indeed God has chosen you, and purified you, and has chosen you above all other women of the worlds. O Mary! Be devoutly obedient to your Lord and prostrate and bow with those bow (in prayer).’” (Quran 3:42-43)

Just as we do not judge all white Christians based on the behavior of, for example, mobs during the French Revolution — or mobs in 21st-century Charlottesville, Virginia, for that matter — the idea of categorizing these videos based on the religion of those depicted is dangerous.

Why is this context important? Because although it is true that violent extremists who identify as Muslim exist, violent extremists are not representative of the more than 1.8 billion Muslim people (nearly a quarter of the world's population) alive. The three videos posted by a leader of the xenophobic and anti-Islam group Britain First and retweeted by the President of the United States in November 2017 are still less so.

The President's tweets not only endanger Muslims in the United States — who have suffered a rise in hate crimes since the divisive 2016 election — they also embolden both white nationalist groups and religious extremists like the Islamic State.

A January 2017 article in The Independent quoted Renad Mansour, a fellow from the Middle East and North Africa Program at the Chatham House think tank:

Dr Mansour cautioned that Mr Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric and executive order were feeding into the narrative used by Isis and other jihadi groups to attract support.

“It plays into this clash of civilisations idea, which is something that global jihadis need as fuel, to claim Americans are against them, that the West is against them,” he added.