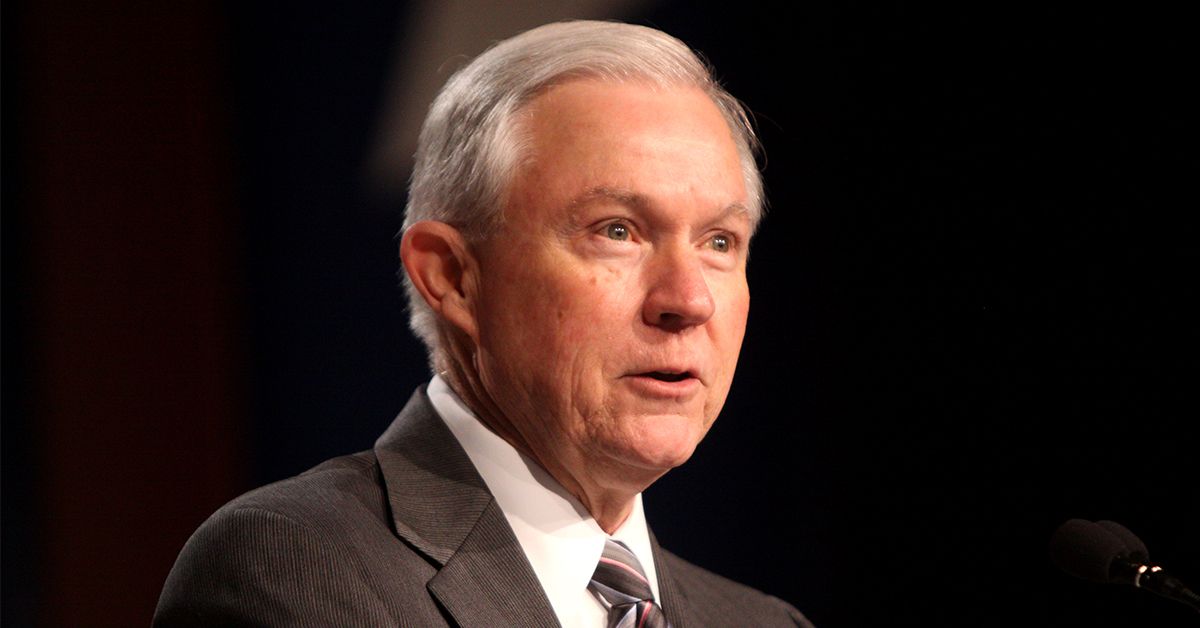

On 3 January 2017, six members of the NAACP were arrested after staging a sit-in at the Mobile, Alabama, office of Sen. Jeff Sessions, who has been selected by President-elect Donald Trump to lead the U.S. Justice Department as Attorney General. In 1986, Sessions was nominated by President Ronald Reagan to serve as a federal judge, but Sessions' nomination was rejected over allegations of "racial insensitivity" on his part, including accusations that Sessions had termed the NAACP "un-American."

The claim that Sessions referred one of the nation's oldest and most prominent civil rights organizations as "un-American" has circulated widely, though during his March 1986 confirmation hearing Sessions denied having used the term to describe the NAACP. Other key accusations levied against him included the claim he had said a white civil rights attorney who litigated a voting rights case was a "disgrace to his race" and that the NAACP and similar organizations "did more harm than good." Sessions disclaimed having made these comments as they were characterized in the testimony of then-Justice Department civil rights lawyer, J. Gerald Hebert. According to a transcript from the hearing, Sessions said at the time:

And I was making this point, as I recall this conversation, and I said, you know, when an organization like the National Council of Churches gets involved in political activities and international relations that people consider to be un-American, they lose their moral authority and ability to function, or to speak with authority to the public because people see them as political.

And I also barreled on and said that that is true; the NAACP and other civil rights organizations, when they leave the basic discriminatory questions and start getting into matters such as foreign policy and things of that nature and other political issues — and that is probably something I should not have said, but I really did not mean any harm by it.

Hebert offered as part of his sworn testimony that he had witnessed Sessions making derogatory comments about the NAACP. Sessions denied making such statements to Hebert, but he said he recalled making somewhat similar comments while talking to Thomas Figures, an African-American assistant U.S. attorney who had an office across the hall from his.

Hebert testified that Sessions said he felt the NAACP "did more harm than good; they were trying to force civil rights down the throats of people who were trying to put problems behind them." Sessions testified at the time that the comment was not said in the context that Hebert testified and denied that he had made direct references to the ACLU and NAACP as "un-American":

I think one time Jerry [Hebert] and I had a conversation where we talked about the civil rights situation and how it stood today, and I made the comment that the fundamental legal barriers to minorities had been knocked down, and that in many areas blacks dominate the political area, and that when the civil rights organizations or the ACLU participate in asking for things beyond what they are justified in asking, they do more harm than good. We discussed that situation.

When asked if he thought Sessions was a racist, Hebert said he did not know. Hebert also testified that Sessions was not only cooperative, but also helpful when he approached Sessions about civil rights cases he was handling:

I have — in conversations over the last couple of years, many of which, I understand, have been read into the record in these proceedings, Mr. Sessions and I have engaged in a number of conversations on subjects that touched racial issues and civil rights issues.

At the same time — and those comments are now a matter of public record here, and I stand by those as having been made. But by the same token, I have prosecuted cases that are highly sensitive and very controversial and, quite frankly, unpopular in the southern district.

And yet I have needed Mr. Sessions' help in those cases and he has provided that help every step of the way. In fact, I would say that my experience with Mr. Sessions has led me to believe that I have received more cooperation from him, more active involvement from him, because I have called upon him.

Another controversial comment that was raised during the hearing was one in which Sessions said of the Ku Klux Klan, "those bastards; I used to think they were OK, but they are pot smokers." The comment was made in the context of a lynching case, while Thomas Figures was standing in the room. Sessions said the comment was made after he heard an anecdote about members of the KKK leaving a meeting and smoking marijuana and believed the comment was so ludicrous that no one would have taken it seriously:

Maybe I was saying I do not like Pol Pot because he wears alligator shoes. All of us understood that the Klan is a force for hatred and bigotry and it just could not have meant anything else than that under those circumstances.

The comment was made while Sessions was involved in prosecuting the case of Klansman Henry Francis Hays, who was convicted of beating and murdering a young black man named Michael Donald, and then hanging his body from a tree. Hays received the death penalty and was executed in 1997.

During his confirmation hearing, Sessions also unequivocally denied an allegation that he had used the N-word in reference to a black county commissioner in Mobile, Alabama.

Neither Sessions nor Hebert returned our requests for comment, and Figures passed away in 2015. But Hebert, who currently serves as director of the Voting Rights and Redistricting Program at the Campaign Legal Center in Washington, D.C., wrote in a 22 November 2016 op-ed for the Washington Post that he stands by his testimony:

Sessions rebutted some of the testimony against him (including that he had called an African American prosecutor who worked for him “boy” and told him to “be careful what you say to white folks”), but he didn’t deny what I said about him. He never apologized for those comments, either, saying only that “I am loose with my tongue on occasion.”

The Republican-controlled Judiciary Committee did not approve his nomination, making him only the second nominee in 50 years to be rejected by the Senate for a federal judgeship. I never had any contact with Sessions again.

Thirty years later, Sessions has been tapped to be the federal government’s top attorney, charged with enforcing the law fairly and protecting the civil rights of all Americans. I have little faith that he will. So once again, I am adding my personal encounters with Sessions to the public record.

The comments I heard him make are three decades old, but his consistent policy positions over the years speak volumes. He falsely charged three African American civil rights activists in Alabama, including a longtime adviser to Martin Luther King Jr., with 29 counts of mail fraud, altering absentee ballots and attempting to vote multiple times. The evidence showed that these activists were simply helping elderly African American voters complete mail-in ballots. All were acquitted of every charge.

Hebert was referring a case that became known as the Marion Three, in which Sessions in his capacity as U.S. Attorney charged three prominent civil rights activists, including Albert Turner, a close associate of Martin Luther King, Jr., with voting fraud:

In 1985, when he was U.S. Attorney in Mobile, Sessions’ office brought indictments over allegations of voter fraud in a number of Black Belt counties, an area in Alabama named for the color of the soil but with a majority black population. In Perry County, Sessions’ office charged three individuals with voting fraud, including Albert Turner, a long-time civil rights activist who advised Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and helped lead the voting rights March in Selma on March 7, 1965, known as "Bloody Sunday" after state troopers and a local posse attacked the protestors.

Prosecutors alleged that Turner, his wife Evelyn, and activist Spencer Hogue altered ballots for a Sept. 1984 primary election.

Robert Turner, Albert’s brother and an attorney in Marion, Ala., said in a phone interview Friday that the defendants — later known as the Marion Three — were trying to assist poor and elderly voters in casting ballots. In some cases, the defendants said they were helping illiterate voters mark their ballots, and only altered ballots when requested.

All three defendants were cleared of any wrongdoing by a jury after a few hours of deliberation.

Session's confirmation hearing for his nomination as head of President Trump's Justice Department is currently scheduled for 10 January 2017.