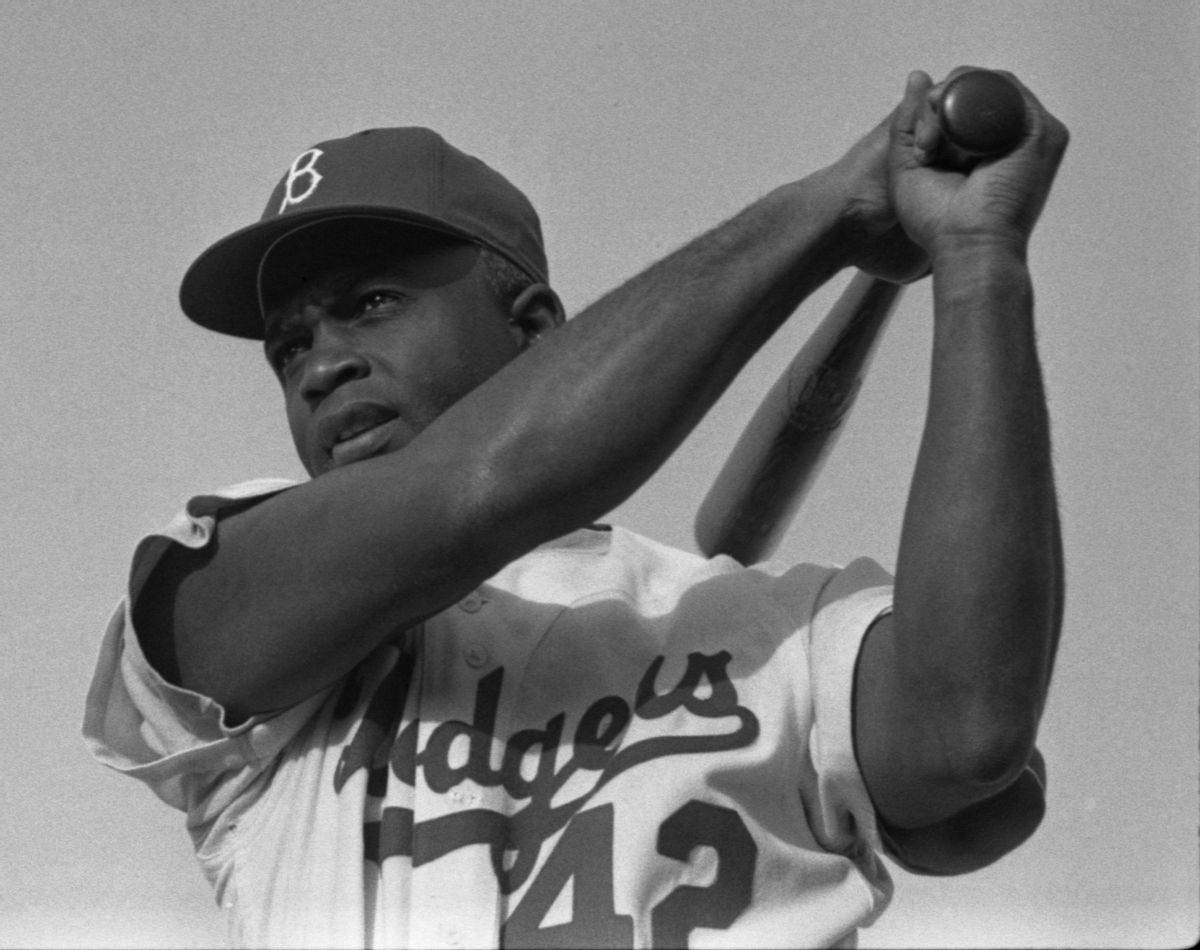

Baseball Hall-of-Famer Jackie Robinson, who died at the age of 53 in 1972, would simply be remembered as one of the greatest players of all time were it not for the color of his skin and the special circumstances of his career. On 15 April 1947, Robinson became the first African American to play major league baseball since the game became completely segregated in the 1880s. He had been hired away from the Kansas City Monarchs, a Negro League team, by Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey, who, in what came to be called "the noble experiment," carefully orchestrated Robinson's introduction to the general public, first via a stint with the minor league Montreal Royals, then by calling him up for his major league debut with the Dodgers at the start of the 1947 season.

With the color line officially broken, the way was paved for more African American players to enter the major leagues, bringing 60 years of segregation in baseball to close. Jackie Robinson ultimately became a much-beloved public figure and an emblem for the changes in race relations that were gradually beginning to occur across America. Years later, Martin Luther King Jr. would honor Robinson as a "legend and a symbol" who "challenged the dark skies of intolerance and frustration." What many people didn't realize was how hard it had been for him.

When he came to write his autobiography, I Never Had It Made, with Alfred Duckett in 1972, Robinson said he felt proud but seemed bitter as well:

It hadn't been easy. Some of my own teammates refused to accept me because I was black. I had been forced to live with snubs and rebuffs and rejections. Within the club, Mr. Rickey had put down rebellion by letting my teammates know that anyone who didn't want to accept me could leave. But the problems within the Dodgers club had been minor compared to the opposition outside. It hadn't been that easy to fight the resentment expressed by players on other teams, by the team owners, or by bigoted fans screaming "nigger." The hate mail piled up. There were threats against me and my family and even out-and-out attempts at physical harm to me.

Some things counterbalanced this ugliness. Black people supported me with total loyalty. They supported me morally: they came to sit in a hostile audience in unprecedented numbers to make the turnstiles hum as they never had before at ballparks all over the nation. Money is America's God, and business people can dig black power if it coincides with green power, so these fans were important to the success of Mr. Rickey's "Noble Experiment."

Some of the Dodgers who swore they would never play with a black man had a change of mind when they realized I was a good ballplayer who could be helpful in their earning a few thousand more dollars in World Series money. After the initial resistance to me had been crushed, my teammates started to give me tips on how to improve my game. They hadn't changed because they liked me any better, they had changed because I could help fill their wallets.

Robinson wrote that despite developing genuine friendships with some of his teammates, and feeling genuine love from many of the fans, he had never stopped feeling like an outsider in his own game, and in his own country:

There I was, the black grandson of a slave, the son of a black sharecropper, part of a historic occasion, a symbolic hero to my people. The air was sparkling. The sunlight was warm. The band struck up the national anthem. The flag billowed in the wind. It should have been a glorious moment for me as the stirring words of the national anthem poured from the stands. Perhaps, it was, but then again, perhaps, the anthem could be called the theme song for a drama called The Noble Experiment. Today, as I look back on that opening game of my first World Series, I must tell you that it was Mr. Rickey's drama and that I was only a principal actor. As I write this twenty years later, I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world. In 1972, in 1947, at my birth in 1919, I know that I never had it made.