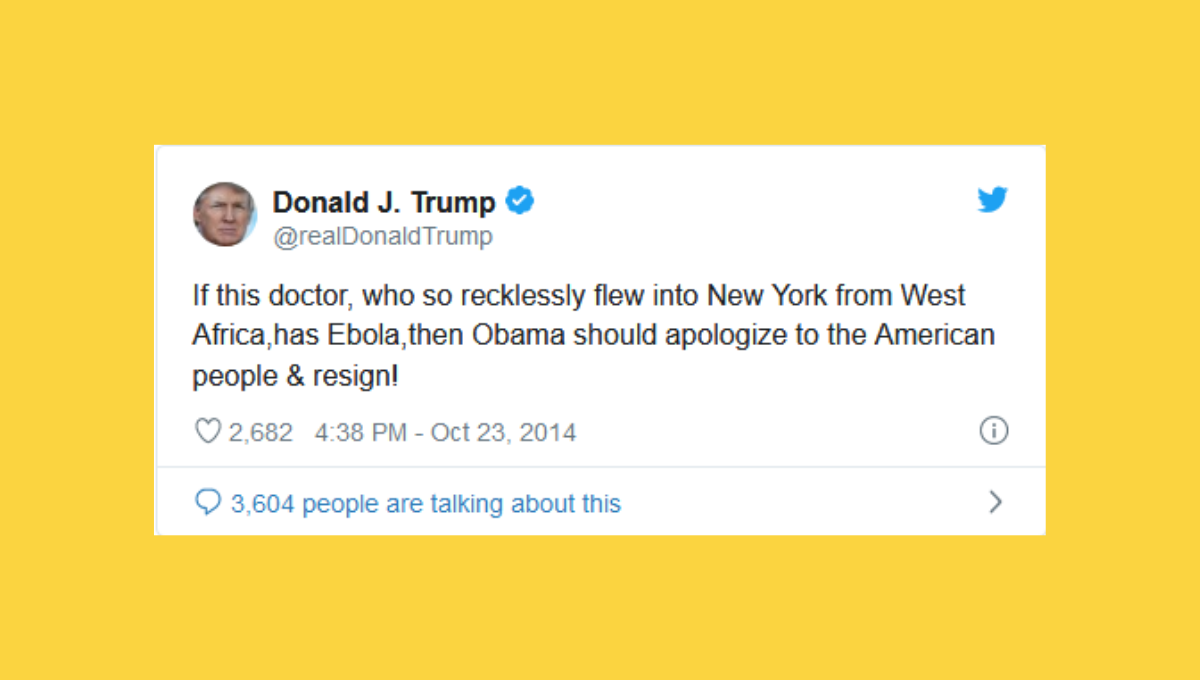

More than one critic of U.S. President Donald Trump has observed that Trump seemingly "has a tweet for everything." That is, whatever the situation today might be, one can find an old Trump tweet about it (or something similar) -- and more often than not that tweet will be a criticism of how someone else dealt with that situation.

One such example was highlighted in the spring of 2020, while the U.S. was dealing with the COVID-19 coronavirus disease pandemic:

The background to the Trump tweet from October 2014 featured above was the Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa that began in 2014. As the outbreak worsened and Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) spread to countries outside West Africa in August 2014, the Obama administration had to formulate policy for protecting the U.S. against it.

Trump (then a private citizen) began tweeting that August, and more frequently and insistently throughout September and October, that the U.S. should ban flights from the affected West African countries. Well into October, however, Democrats in Congress and in the Obama administration still differed over the merits and practicality of implementing a West African travel ban:

Worried about the political fallout from the Ebola outbreak, vulnerable Senate Democrats are declaring their support for a U.S. travel ban from the afflicted countries in West Africa.

In multiple cases, the Democrats are shifting from their earlier positions on the question, despite arguments from senior U.S. medical officials and the White House that stiff restrictions would only make it harder to prevent an infected person from entering the country ...

Some lawmakers have also stumbled over the meaning of a travel ban. There are currently no direct flights to the U.S. from Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea -- the three West African nations where the Ebola outbreak is occurring -- so any restrictions would have to be enforced at connecting airports in Europe. Traveler screenings have already been implemented at five U.S. airports, but they likely would have to be continued anyway to catch passengers who fly to Europe, but do not immediately transfer to a U.S.-bound flight.

With that in mind, as The New York Times noted, GOP leaders have subtly shifted their focus from an outright travel ban to demanding tighter airport screenings and the creation of "no-fly" lists to make sure people who have been exposed to Ebola do not board flights.

At that time, the Obama administration did not implement a full travel ban but rather implemented travel restrictions that forced passengers originating from affected West African countries to enter the U.S. through one of five airports with screening procedures in place.

Dr. Craig Spencer, who had been working with Doctors Without Borders in Guinea treating Ebola patients, completed his work there on Oct. 12, 2014, before the U.S. travel restrictions were put in place. Spencer then returned to the U.S. from Guinea, traveling through Europe and arriving in New York on Oct. 17, but several days later he fell ill, was hospitalized, and became the first person in New York City to test positive for the Ebola virus. When it was learned that the night before his hospitalization Spencer had traveled on a subway, visited a bowling alley, and then taken a taxi home, health officials began searching for anyone who might have come into contact with him. Spencer was the "doctor who so recklessly flew into New York from West Africa" referenced in Trump's tweet:

Several months after those events, Spencer published a letter in the New England Journal of Medicine, in which (in the words of Vox) he blamed "the media (and self-serving politicians) for stirring fear and hate [and] unnecessarily vilifying returning humanitarians like himself despite the fact that we know from science it would have been almost impossible for him to transmit the virus." That letter read (in part):

While treating patients with Ebola in Guinea, I kept a journal to record my perceived level of risk of being infected with the deadly virus. A friend who'd volunteered previously had told me that such a journal comforted him when he looked back and saw no serious breach of protocol or significant exposure. On a spreadsheet delineating three levels of risk — minimal, moderate, and high — I'd been able to check off minimal risk every day after caring for patients. Yet on October 23, 2014, I entered Bellevue Hospital as New York City's first Ebola patient.

Though I didn't know it then — I had no television and was too weak to read the news — during the first few days of my hospitalization, I was being vilified in the media even as my liver was failing and my fiancée was quarantined in our apartment. One day, I ate only a cup of fruit — and held it down for less than an hour. I lost 20 lb, was febrile for 2 weeks, and struggled to the bathroom up to a dozen times a day.

The morning of my hospitalization, I woke up knowing something was wrong. I felt different than I had since my return — I was more tired, warm, breathing fast. When I took my temperature and called to report that it was elevated, in some bizarre way I felt almost relieved. Although my worst fear had been realized, having the disease briefly seemed easier than constantly fearing it.

My activities before I was hospitalized were widely reported and highly criticized. People feared riding the subway or going bowling because of me. The whole country soon knew where I like to walk, eat, and unwind. People excoriated me for going out in the city when I was symptomatic, but I hadn't been symptomatic — just sad. I was labeled a fraud, a hipster, and a hero. The truth is I am none of those things. I'm just someone who answered a call for help and was lucky enough to survive.

After my diagnosis, the media and politicians could have educated the public about Ebola. Instead, they spent hours retracing my steps through New York and debating whether Ebola can be transmitted through a bowling ball. Little attention was devoted to the fact that the science of disease transmission and the experience in previous Ebola outbreaks suggested that it was nearly impossible for me to have transmitted the virus before I had a fever. The media sold hype with flashy headlines — “Ebola: `The ISIS of Biological Agents?'”; “Nurses in safety gear got Ebola, why wouldn't you?”; “Ebola in the air? A nightmare that could happen”1-3 — and fabricated stories about my personal life and the threat I posed to public health, abdicating their responsibility for informing public opinion and influencing public policy.

Meanwhile, politicians, caught up in the election season, took advantage of the panic to try to appear presidential instead of supporting a sound, science-based public health response.

We all lose when we allow irrational fear, fueled in part by prime-time ratings and political expediency, to supersede pragmatic public health preparedness.

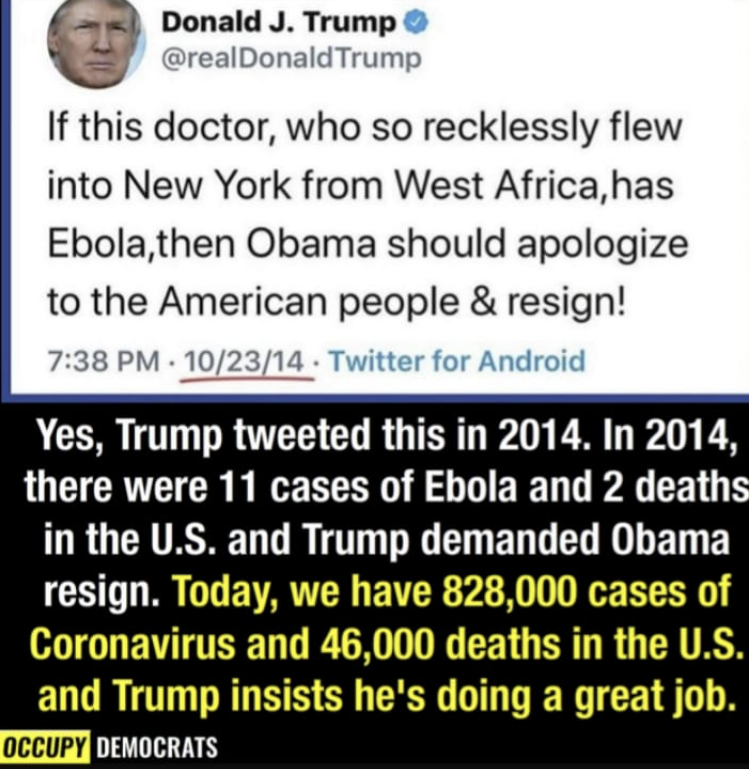

The Occupy Democrats meme reproduced above is correct in noting that the overall impact of the 2014-16 Ebola outbreak on the U.S. was a total of 11 confirmed cases and two deaths:

Overall, eleven people were treated for Ebola in the United States during the 2014-2016 epidemic. On September 30, 2014, CDC confirmed the first travel-associated case of EVD diagnosed in the United States in a man who traveled from West Africa to Dallas, Texas. The patient (the index case) died on October 8, 2014. Two healthcare workers who cared for him in Dallas tested positive for EVD. Both recovered.

On October 23, 2014, a medical aid worker who had volunteered in Guinea was hospitalized in New York City with suspected EVD. The diagnosis was confirmed by the CDC the next day. The patient recovered.

Seven other people were cared for in the United States after they were exposed to the virus and became ill while in West Africa, the majority of whom were medical workers. They were transported by chartered aircraft from West Africa to hospitals in the United States. Six of these patients recovered, one died.

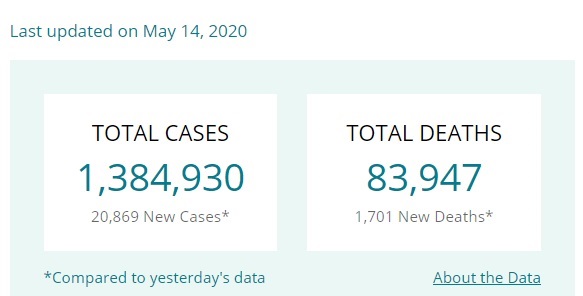

As of this writing (mid-may 2020), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was reporting a total of 1,384,930 COVID-19 cases in the U.S., with 83,947 deaths:

Although the Trump administration imposed travel restrictions on persons entering the U.S. from China in early February 2020 as the COVID-19 virus was spreading internationally, an estimated 430,000 people flew to the U.S. from China between Dec. 31, 2019 (when China first informed the World Health Organization about cases of the coronavirus in Wuhan) and the implementation of those travel restrictions a month later. Those restrictions also included exemptions for U.S. citizens, permanent residents, and their relatives, which allowed nearly 40,000 more people to enter the U.S. from China in the two months after Trump imposed those restrictions.