There are many stories and myths surrounding the origins of Thanksgiving. In attempting to debunk them, the internet often ends up creating more. Ahead of Indigenous Peoples Day on Oct. 11, 2021, we address one particular claim that spread across the internet about the relationship of this holiday to another tragic part of Native American history.

Our readers sent one story our way that claimed Thanksgiving originated from the 1637 massacre of the Pequot people. In the aftermath of the massacre, the governor of Massachusetts declared a day of Thanksgiving, in celebration. Versions of the claim have popped up in articles published by outlets such as the Huffington Post:

I learned that in 1637 the body of a white man was discovered dead in a boat. Armed settlers — which we tell our children were God fearing, gentle, sharing, kind Pilgrims — invaded a Pequot village. They also set the village, which included many children, on fire. Those who were lucky enough to escape the fire were systematically sought, hunted down and killed. While many, including historians, still debate what exactly happened this day, also known as the Pequot Massacre, it directly led to the creation of “Thanksgiving Day.” This is what the governor of Bay Colony had to say days after the massacre, “A day of thanksgiving. Thanking God that they had eliminated over 700 men, women and children.”

A post on Facebook claims:

In 1637, white colonizers turned on the Pequot tribe who had taught them to farm, take care of the land, and raise food. The white male colonizers slaughtered 700 Pequot men, women, children, and elders, and then celebrated. They “gave thanks” for the massacre they had just carried out. They continued celebrating like this when they massacred indigenous people until Lincoln decreed the celebration should only happen once a year after he himself had ordered the massacre of a group of indigenous people.

A 2019 article in Time magazine stated: "The first official mention of a “Thanksgiving” celebration occurs in 1637, after the colonists brutally massacre an entire Pequot village, then subsequently celebrate their barbaric victory."

While the Pequot massacre did indeed take place, we spoke to historians and learned that there is little evidence proving that it was the origin point of the modern holiday known as Thanksgiving.

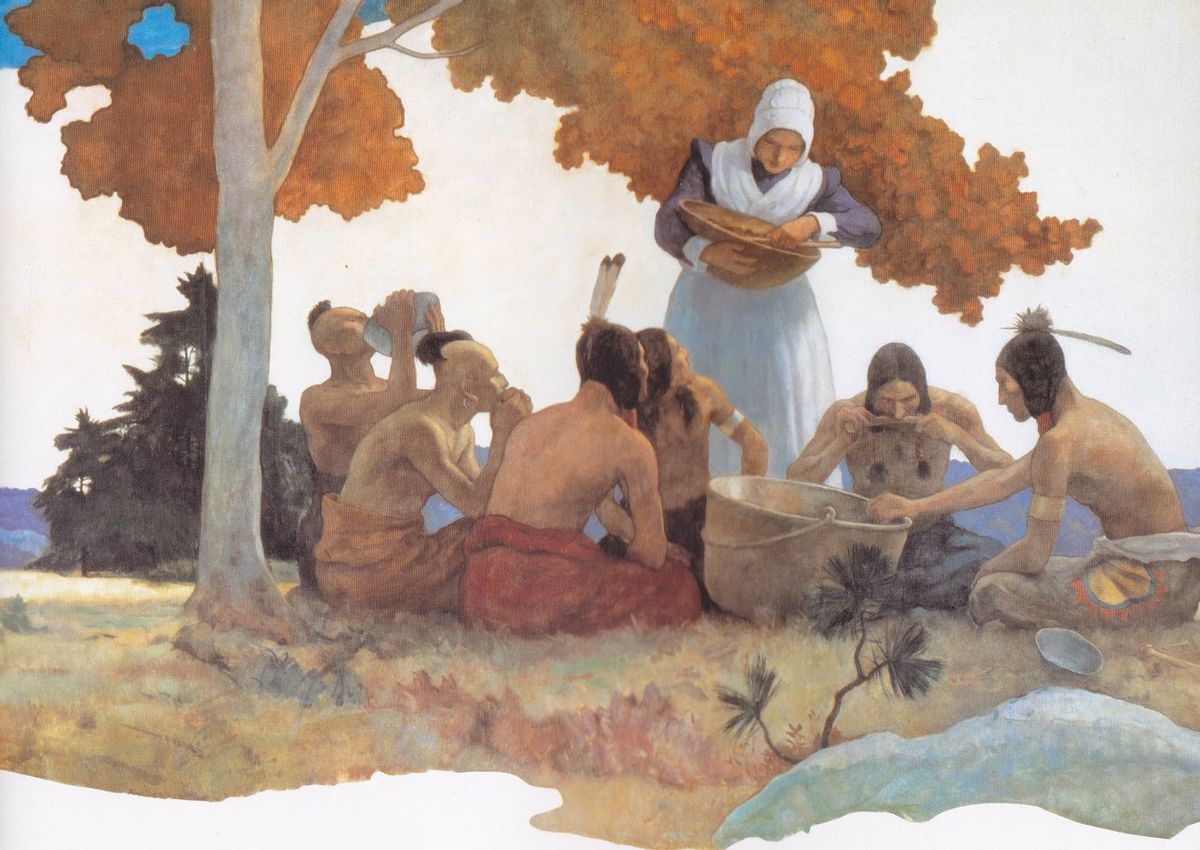

The main narrative around Thanksgiving is that it is modeled on a feast in 1621 when the Native American Wampanoag people and English colonists broke bread together. But that story obscures the context around this feast. Native American activists and historians have long highlighted the history of genocide and displacement of indigenous communities surrounding the arrival of colonists on the shores of what would become the United States of America. Since the 1970s, a group of New England Native activists have marked the fourth Thursday in November, or Thanksgiving Day, as the “National Day of Mourning.”

Here is what we do know about the events of 1637. In the summer of 1637, an armed force of English Puritans led an attack on the fortified Pequot village of Mystic in Connecticut, resulting in the deaths of around 500 Native American men, women, and children, though some estimate the numbers were higher. The village was burned to the ground, and marked the first major defeat of the Pequot people in what was a three year war over their lands.

The event has been described as a “massacre,” and a “slaughter.” John Mason, commander of the Connecticut forces that wiped out the village described setting the fort of the village on fire, “And thus in little more than one Hour’s space was their impregnable Fort with themselves utterly destroyed, to the Number of six or seven Hundred, as some of themselves confessed.”

The aftermath of the massacre has been subject to interpretation, and in some cases, misrepresentation.

Here is what John Winthrop, the governor of the state of Massachusetts, said, according to his journal, on June 15, 1637: “There was a day of thanksgiving kept in all the churches for the victory obtained against the Pequots, and for other mercies [...]” Another such day was also declared in October for more victories against the Pequots.

This appears to be the basis for many arguments that this was the true origin of our modern-day thanksgiving. In actuality, churches declared days of thanksgivings quite regularly. Winthrop mentions them frequently in his journals. In July 1630, before the Pequot massacre, he described “a day of thanksgiving in all the plantations,” for the safe arrival of ships from England. One day of thanksgiving was even declared in September 1641 “for the good success of the Parliament in England.”

We spoke to David Silverman, professor at George Washington University, and author of the book “This Land is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving.”

When asked about the connection between the 1637 day of thanksgiving and the holiday we know today, he said: “There is no question that Connecticut and Massachusetts had a thanksgiving after [those events], a lot of people did it [...] but to draw the connection between that and the modern holiday is untenable. Thanksgivings were a tradition amongst English people often to mark a gift from god [...] [The quote’s usage] is taking that particular thanksgiving out of context. There were hundreds, if not thousands of thanksgivings, some of them were related to military conquests of Indian people and most were not.”

This viewpoint was echoed by Chris Newell, director of education of Akomawt Educational Initiative, and the former education supervisor at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center.

“When it comes to the 17th century English 'days of thanksgiving,' they have no resemblance to the holiday we celebrate today,” he told us. “That holiday was not created until the 19th century. The English day of thanksgiving would have been a day of prayer. If they won a victory in battle that would have been a day of thanksgiving, which was normally a day of fasting, totally different from a feast.”

Kate Sheehan, a spokesperson for the Plimouth Plantation museum in Plymouth, Massachusetts, also told The New York Times that while a day of thanksgiving was noted in the Massachusetts Bay and the Plymouth colonies after the attack on the village, it is not accurate to say it was the basis for our modern Thanksgiving.

So how did the modern thanksgiving holiday come about? Both Newell and Silverman pointed out that the official holiday was coined by President Abraham Lincoln.

In October 1863, Lincoln issued the Thanksgiving Proclamation, after the victory of the Union over the Confederacy: “I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, …to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving…”

“Lincoln was trying to bring the country together after the civil war, so the creation of propaganda by the government to do this was something that was not out of bounds,” Newell said. “There was already, in several states, the tradition of having Thanksgiving on different days. They wanted to nationalize it, and bring it together.”

Thanksgiving day owes its origins in part to Sarah Josepha Hale (a woman also known for penning the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb”), who lobbied through a letter-writing campaign to members of Congress and other government officials for such a holiday. She wrote: “It now needs National recognition and authoritative fixation, only, to become permanently, an American custom and institution."

According to Newell, the narrative we know today, “of a pleasant meeting between natives and the English” is a popular one that Hale pushed and magazines, writers, and even schoolbooks took up as fact. “They wanted a pleasant story” that could serve as a foundational event everyone could unite on, Newell argued.

While a harvest feast did take place in 1621, he added that another thanksgiving had also taken place in the Virginia colony, “but because it was in the South, Virginia could not be attached” to the popular narrative after the Civil War. “This was a lie based on the political situation at the time,” Newell said. Indeed, Virginians do claim to have hosted a more strictly religious Thanksgiving in 1619, minus the feasting.

Silverman argued that the friendly association of pilgrims and Indians, and the Wampanoag people in particular, to Thanksgiving “is an invention of the late 19th and early 20th century.” In an article for The Atlantic, he elaborated:

Contrary to the Thanksgiving myth, though, friendliness does not account for the alliance the Wampanoag tribe made with the nascent Plymouth settlement. The Wampanoags had an internal politics all their own; its dynamics had been shaped by many years of tense interaction with Europeans, and by deadly plagues that ravaged the tribe’s home region as the pace of English exploration accelerated.

[...]

The so-called first Thanksgiving was the fruit of a political decision on Ousamequin’s [the Chief of the Wampanoag] part. Violent power politics played a much more important role in shaping the Wampanoag-English alliance than the famous feast. At least in the short term, Ousamequin’s league with the newcomers was the right gamble, insofar as the English helped to fend off the rival Narragansetts and uphold Ousamequin’s authority. In the long term, however, it was a grave miscalculation. Plymouth and the other New England colonies would soon go on to conquer Ousamequin’s people, just as the Frenchman’s curse had augured and just as the Wampanoags who opposed the Pilgrims feared that they would.

The incorrect association of Thanksgiving to the Pequot massacre is a small part of a larger obscuring of the full context and origins of Thanksgiving over the years, something experts seek to correct today. We thus rate this claim as "False."

“Thanksgiving Day | Meaning, History, & Facts.” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Thanksgiving-Day. Accessed 6 Oct. 2021.“Thanksgiving Wasn’t Always a National Holiday. This Woman Made It Happen.” Time, https://time.com/4577082/thanksgiving-holiday-history-origins/. Accessed 6 Oct. 2021."The Pequot War." Mashantucket (Western) Pequot Tribal Nation. https://www.mptn-nsn.gov/pequotwar.aspx. Accessed 6 Oct. 2021.“The Thanksgiving Tale Is a Harmful Lie. As a Native American, I’ve Found a Better Way to Celebrate.” Time, https://time.com/5457183/thanksgiving-native-american-holiday/. Accessed 6 Oct. 2021.Winthrop, John. The Journal of John Winthrop, 1630-1649. Accessed 6 Oct. 2021.