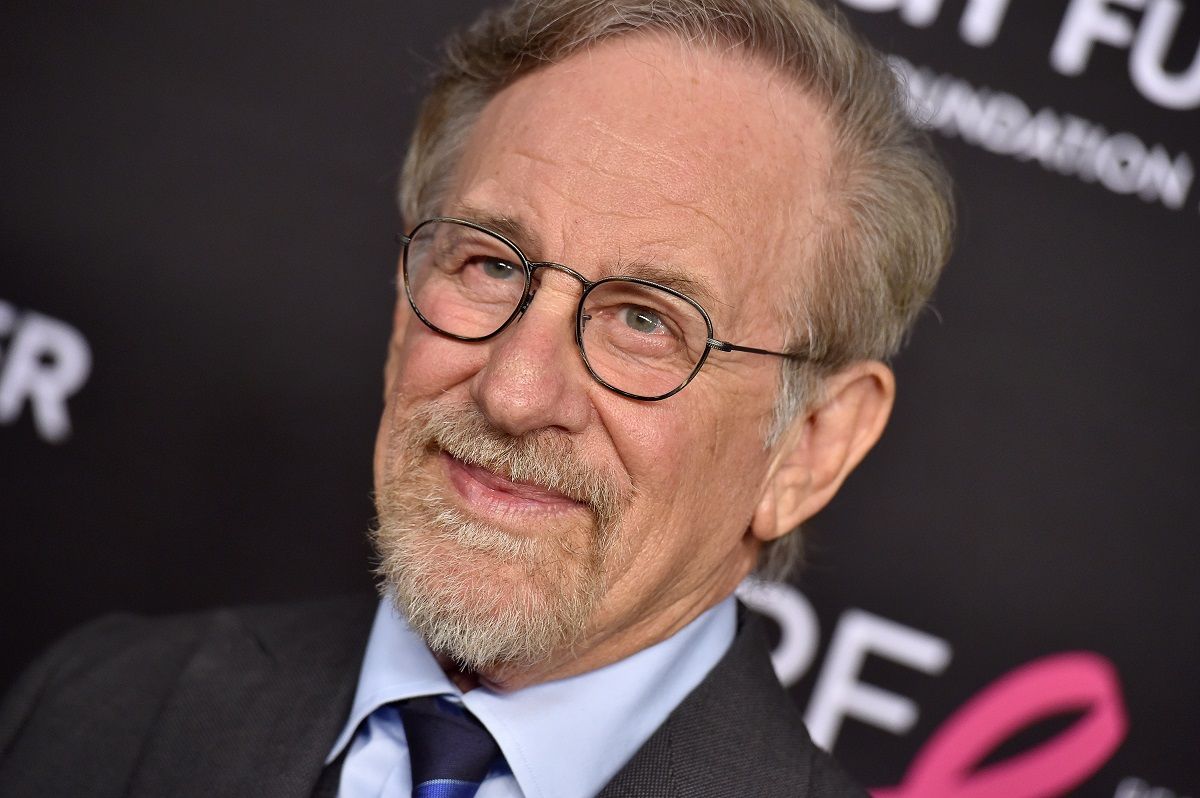

We all admire the wunderkind — that rare person of remarkable talent and ability who achieves great success or acclaim at an early age. Prodigies usually reach legendary status through their extraordinary accomplishments alone, but the occasional wunderkind-in-a-hurry helps his nascent legend along with a little fanciful embroidery. Such is the case with film director Steven Spielberg, who began garnishing his past with a bit of fantasy even from the earliest days of his professional career.

Spielberg's first practical exposure to the workings of Hollywood studios came in the summers just before and after he graduated from high school in the mid-1960s, when he apprenticed at Universal Studios as an unpaid assistant in the studio's television department. Over the subsequent years, those humble beginnings morphed into a more and more elaborate tale told by Spielberg about how he had supposedly sneaked into Universal dressed in business attire, commandeered an empty bungalow, and set up shop on the premises for over two years before someone finally discovered didn't actually belong there:

In one of his earliest tellings of the tale, to The Hollywood Reporter in 1971, Spielberg claimed: "One day in 1969 [sic], when I was twenty-one, I put on a suit and tie and sneaked past the guard at Universal, found an empty bungalow, and set up an office. I then went to the main switchboard and introduced myself and gave them my extension so I could get calls. It took Universal two years to discover I was on the lot."

In a previous (1969) interview with the Reporter, Spielberg had said, "Every day, for three months in a row, I walked through the gates dressed in a sincere black suit and carrying a briefcase. I visited every set I could, got to know people, observed techniques, and just generally observed the atmosphere."

And in his 1970 interview with Rabbi William M. Kramer for Heritage-Southwest Jewish Press, Spielberg confessed, "To get by the guard at the gate I lied a lot."

By 1985, Spielberg had added the detail that he first made his way onto the Universal lot by sneaking off the tram during a public studio tour:

The fateful day when this movie-mad child got close to his Hollywood dream came in the summer of 1965, when 17-year-old Steven, visiting his cousins in Canoga Park, took the studio tour of Universal Pictures. "The tram wasn't stopping at the sound stages," Steven says. "So during a bathroom break I snuck away and wandered over there, just watching. I met a man who asked what I was doing, and I told him my story. Instead of calling the guards to throw me off the lot, he talked with me for about an hour. His name was Chuck Silvers, head of the editorial department. He said he'd like to see some of my little films, and so he gave me a pass to get on the lot the next day. I showed him about four of my 8-mm films. He was very impressed. Then he said, 'I don't have the authority to write you any more passes, but good luck to you.'"

The next day a young man wearing a business suit and carrying a briefcase strode past the gate guard, waved and heaved a silent sigh. He had made it! "It was my father's briefcase," Spielberg says. "There was nothing in it but a sandwich and two candy bars. So every day that summer I went in my suit and hung out with directors and writers and editors and dubbers. I found an office that wasn't being used, and became a squatter. I went to a camera store, bought some plastic name titles and put my name in the building directory: Steven Spielberg, Room 23C."

So much for the legend. In fact, Steven Spielberg's entree to the Universal lot was gained while he was a 16-year-old on break from his junior year of high school in Arizona (in late 1963 or early 1964), and it had nothing to do with his sneaking onto the premises — his visit was arranged in advance by his father (through an intermediary) with Chuck Silvers, assistant to the editorial supervisor for Universal TV, as Silvers recalled to Spielberg biographer Joseph McBride:

Arnie called me and said, "The son of an old friend of mine from GE is here. He's in high school and he's a real film bug. Would you mind showing him around postproduction?" I said, "Fine." Steven was on some kind of long weekend from school. So [Arnie] sent Steven.

Because it was raining, I didn't try to show him a hell of a lot of stuff. I showed him postproduction, editorial, Moviolas; I do remember him saying he had seen Moviolas. We spent the rest of the day talking and walking. He said, "I make movies." He told me about the movies he had made. I asked basic questions of him, how he became involved in film.

After Spielberg returned to Arizona, he kept up an occasional correspondence with Chuck Silvers and returned to Universal during the summer of 1964 to work as an unpaid clerical assistant. It was then that one of the few details from Spielberg's imaginative account of his early days at Universal Studios actually played out -- according to Chuck Silvers, young Steven did have to use his ingenuity to get onto the lot each day: "The first time he came back there I got him a pass to come on the lot. I couldn't get him a permanent pass on the lot. Steven found his own way of getting on the lot. Steven was able to walk onto the lot just about any time he damned well pleased."

But both Silvers and his co-worker divulged to biographer McBride that the tale about Spielberg's finding and occupying an empty office at Universal was a bit of creative fiction on the fledgling director's part to romanticize his early background:

Silvers shared an office with a middle-aged woman named Julie Raymond, the Universal Television editorial department's purchasing agent, in charge of filling orders with laboratories and other subcontractors. "Spielberg was sixteen when I first met him," she remembers. "He was working on the lot when he was in high school. Chuck told him he could use our office to take phone calls. Chuck brought him into the office and told me the kid was floating around the lot. Spielberg used to come in to take calls and work on scripts."

Spielberg helped her during the summers of 1964 and 1965 by "tearing down" purchase orders (i.e., separating colored sheets and carbons) and routing copies of them to various departments. He also ran errands to the Technicolor laboratory adjacent to the studio lot, and to other suppliers housed in that building.

In his accounts of his early days at Universal, Spielberg has never mentioned his office work with Julie Raymond. Instead he has gone to considerable lengths to turn mundane reality into romantic myth, saying that after bluffing his way past the guard and finding an empty office, he commandeered it, listing his name in plastic letters next to Room 23C in the building's directory.

"I've never been in that office, let's say," Chuck Silvers comments diplomatically. Julie Raymond's response is more blunt: "He made up a lot of stories about finding an empty editing office and moving into it. That's a bunch of horseshit."

Even though Spielberg embroidered the reality of his first few summers at Universal, he certainly did make the most of his experience. At the tender age of 22 he directed Joan Crawford in the pilot episode of Rod Serling's Night Gallery for Universal Television, and by the age of 30 he had helmed two of the top-grossing films of all time, Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind — just a small part of a stellar cinematic career that also included box office favorites Raiders of the Lost Ark, E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, and the Academy Award-winning Schindler's List (the latter of which nabbed top honors in 1993 in seven categories, including Best Picture and Best Director).

Embellishment is part of the magic that is Hollywood. Or, as comedian George Burns was wont to say about the tall tales woven into the fabric of his own life: "Most of what I say is true. The rest is show business."