New research suggests some species of reef sharks are “functionally extinct” in about one-in-five coral reef ecosystems globally.

The findings did not extend to all sharks around the world and only focused on select species who live all or part of their lives near coral reefs.

A global study published in July 2020 found that reef sharks are “functionally extinct” in some parts of the world, highlighting for the first time the previously undocumented widespread decline of the ocean’s top predators.

Species considered functionally extinct are those unable to reproduce or fulfill their role in an ecosystem. On the other hand, extinction involves the death of the last individual of a certain species. A handful of animals have become functionally extinct within the last few decades, including the northern white rhinoceros.

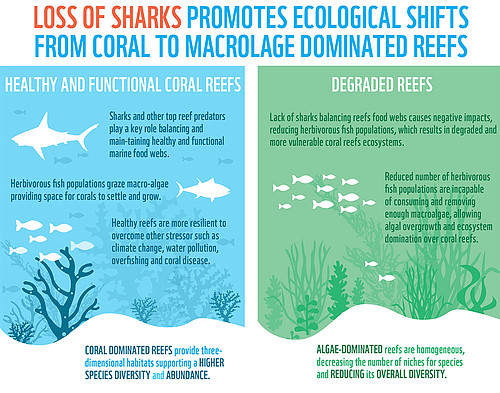

In the case of reef sharks, which include species that spend a majority of their life near reef ecosystems — like whitetip and blacktip reef sharks, lemon sharks, and great hammerheads — functional extinction means they no can no longer contribute to the marine food web through preying on large, herbaceous fish and could ultimately lead to catastrophic consequences in coral reef systems that depend on them. As the top predator in their ecosystem, reef sharks play a key role in balancing marine food webs, according to the World Wildlife Fund.

But overfishing has depleted their number to the point that some may no longer be able to fulfill their role in the marine ecosystem, according to the study published in the journal Nature.

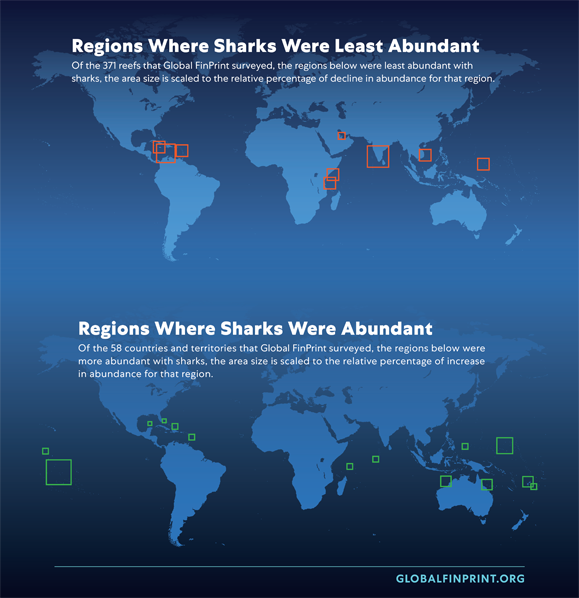

Though it's been known that the overexploitation of marine resources has “devastated” shark populations in recent decades, understanding their ecological status has largely relied on catch records and limited data. To bridge this information gap and to better understand shark species that live in coastal environments, a team of researchers from Dalhousie University in Canada deployed 15,000 underwater video cameras at hundreds of coral reefs around the world in 60 tropical countries. Over four years, this data was used in order to build a baseline understanding of the animals. Operating as part of the Global FinPrint conservation and research program, video stations included a camera mounted on a frame that contained more than 2 pounds (1 kilogram) of fish bait and were aptly given the nickname "chum cam."

“This study pulls back the curtain on the state of reef sharks around the world,” said study lead author Aaron MacNeil, associate professor in Biology at Dalhousie, in a university statement. “While reef sharks have been studied in a few places, this work gives us a basis for understanding the extent and magnitude of the impact people have had on reef sharks, and what we might do about it.”

Collectively, more than 15,000 video hours and 59 species of sharks were analyzed in what became the largest and most comprehensive collection of data on reef sharks.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=3&v=HqErSOEjHe4&feature=emb_logo

The results revealed the “profound impact” that overfishing has had on shark populations in some parts of the world. One-in-five reef systems studied were void of vital reef sharks and in 800 survey hours, just three reef sharks were seen around reefs located in the Dominican Republic, the French West Indies, Kenya, Vietnam, the Windward Dutch Antilles, and Qatar.

As part of their work, the researchers also identified conservation measures that could help shark populations recover. Countries with effective shark conservation include those that were generally well-governed and have banned shark fishing or introduced science-based management strategies like those seen in Australia, the Bahamas, French Polynesia, the Maldives, the United States, and the Federated States of Micronesia. Countries with designated shark sanctuaries, for example, saw 50% more sharks compared with nations without such protections. The researchers estimate that putting protective measures in place could see a 15% increase in shark populations.

“Although our study shows substantial negative human impacts on reef shark populations, it’s clear the central problem exists in the intersection between high human population densities, destructive fishing practices, and poor governance,” said Demian Chapman, biologist and associate professor at Florida International University.

“We found that robust shark populations can exist alongside people when those people have the will, the means, and a plan to take conservation action.”

Global demand for shark products like fins and meat has contributed to the decline of many species, and a 2014 study conducted by the International Union for Conservation of Nature Shark Specialist Group found overfishing remains one of the biggest threats to sharks and rays -- as many as one-quarter of species are threatened by extinction.

Sharks grow more slowly and produce fewer young than many other fish species, which makes them particularly vulnerable to overfishing. Destructive fishing methods like gillnets, longlines, or shark finning further contributes to their decline, according to marine conservation organization Oceana.