Between 1789 and 1916, no Supreme Court nominee was subjected to public senate hearings. However ...

One nomination, in 1873, was held up by closed-door committee hearings. Furthermore, the Senate did not wait "for decades" after Brandeis in order to quiz nominees again, and one nominee was questioned for hours in a public hearing in January 1925.

In March 2022, MSNBC host Lawrence O'Donnell outlined some interesting historical context for the grilling of U.S. Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson by Republicans during Senate confirmation hearings.

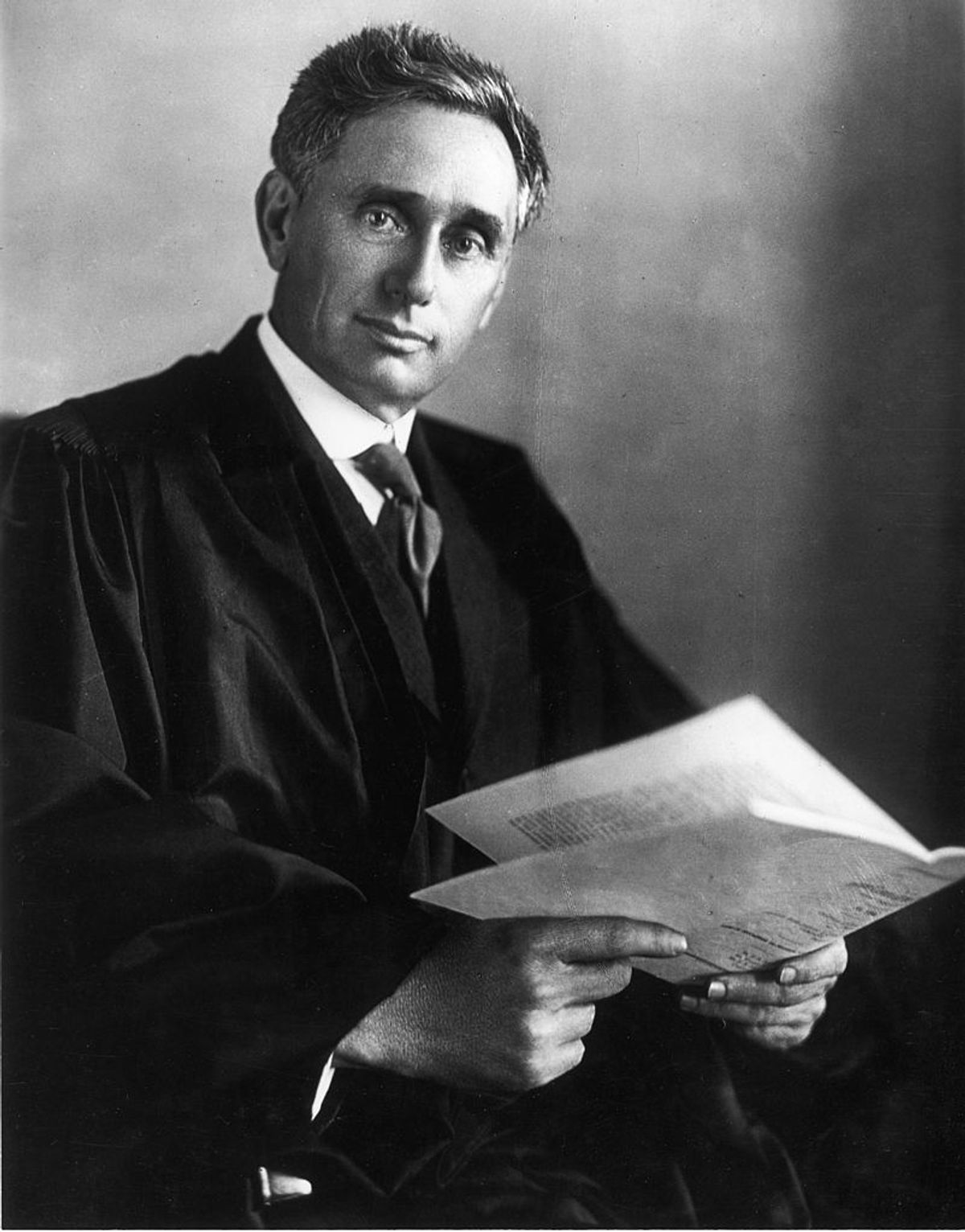

O'Donnell claimed that the tradition of public confirmation hearings for Supreme Court nominees was not in place for the dozens of white Christian men who assumed a seat on the court after its establishment in 1789, but was urgently created for the first Jewish nominee Louis Brandeis in 1916.

O'Donnell's presentation of the facts was highly accurate. His argument — that the tradition of rigorous and hostile senate confirmation hearings was started in response to the nomination of the first Jewish justice — was largely correct. However, he did omit to mention a closed-door hearing for one nominee in 1873, and he mistakenly claimed the Senate "stopped asking questions for decades" after Brandeis, when in fact, just nine years later, another nominee was grilled for several hours by Senate committee members. We are therefore issuing a rating of "Mostly True."

What Lawrence O'Donnell Said

O'Donnell made the claim on Twitter on March 22, where he wrote: "For the 1st 127 years when only white Christian men were allowed to be Supreme Court Justices, there were zero confirmation hearings. Confirmation hearing was invented for the 1st Jewish nominee."

Earlier, he devoted a segment on his MSNBC show "The Last Word" to dissecting the demographic and historical background of the nomination of Jackson who, if she is confirmed, would become the first Black woman to sit on the nation's highest court. O'Donnell explained:

Most of the 115 Supreme Court justices did not even graduate from law school. Only 49 of them were actually law school graduates. For the first 127 years, the Supreme Court was a bastion of affirmative action for white Christian men only ... And not one of them ever had to answer a single question from a senator about anything. Not one of them had confirmation hearings. Not one. At least one of those people was confirmed by the full senate the day after he was nominated. That's how easy it was.

Then, in 1916, came the first Jewish nominee for the United States Supreme Court — Harvard Law School graduate Louis Brandeis. And that is when the confirmation hearing had to be invented. The white Christian men of the senate wanted to ask some questions of the first Jewish nominee to the Supreme Court.

After Justice Brandeis was confirmed, the senate stopped asking questions for decades. They had no questions for Stanley Reed, in 1938 — the last Supreme Court justice who did not graduate from law school. Only in the television age did confirmation hearings become routine for Supreme Court justices, and that was entirely because senators wanted to be on TV. [Emphasis is added].

Early History of Senate Confirmation Hearings

According to research conducted by the Congressional Research Service — a non-partisan and highly reliable source — there were 101 nominations of Supreme Court associate or chief justices between 1789 and 1916. Of those, none was subjected to public hearings of any Senate committee, thus effectively supporting the first part of O'Donnell's claim.

In January 1916, that changed dramatically. After the death of Justice Joseph Lamar, Democratic President Woodrow Wilson nominated Louis Brandeis, a progressive lawyer born in Kentucky but based in Massachusetts, and known for suing major corporations, defending workers' rights, and advocating privacy protections.

Many Republicans fiercely opposed Brandeis's nomination, in part because they portrayed him as a "radical" and a "socialist," but also, undoubtedly, because Brandeis was Jewish. Senators would subject Brandeis to an unprecedented 19 days of committee hearings (although he himself did not attend in person), and it would take four months for his appointment to be confirmed — still a record for the slowest successful Supreme Court confirmation process in history.

In the end, the Senate confirmed his appointment by 47 votes to 22 in June 1916, and Brandeis served on the court until 1939, becoming one of the major legal figures in the United States in the 20th century.

While Brandeis was the first Supreme Court nominee subjected to public hearings — contentious, protracted hearings at that — the Senate had held closed-door hearings on one occasion in the previous 127 years.

In December 1873, President Ulysses S. Grant nominated Attorney General George Henry Williams to serve as Supreme Court Chief Justice. Initially, the Senate Judiciary Committee recommended his nomination be confirmed, but later that month, reversed course after the emergence of several rather murky allegations of corruption and embezzlement against Williams.

After holding two "executive" (that is, private) sessions, the committee members unanimously opposed Williams' ascension, and in January 1874, Williams himself asked Grant to withdraw his name from consideration, which Grant duly did.

After Brandeis, the Senate largely resumed its previous practice of confirming or rejecting Supreme Court nominations without the need for substantial public hearings. However, there were closed hearings in 1922, and in 1925, the Senate judiciary committee held a public hearing on the nomination of Attorney General Harlan Stone. There, committee members grilled Stone for several hours, in what was the first ever occasion on which a Supreme Court nominee appeared in person to answer questions submitted by the senate.

That spectacle took place less than nine years after the Brandeis hearings. So O'Donnell's claim that after Brandeis, "the senate stopped asking questions for decades" is not right. Senate hearings were very rare, and the intensity of scrutiny to which Brandeis was subjected was indeed unique at that time. However, he was not the only Supreme Court nominee made to sweat over his confirmation during that era.

The next public hearing came in 1930, and during that decade Supreme Court nominees were as likely as not to face public hearings in the judiciary committee. From the 1940s onward, though, Supreme Court nominees were more likely than not to be subjected to committee hearings.