In a minority of U.S. states, the law allows for the possibility that resisting an unlawful arrest is legally justified in some circumstances.

Throughout most of the United States, there is absolutely no right to resist unlawful arrest; even in the places where the law allows for the possibility of such a right, it is a limited one.

The rights of the individual in the face of state power has been one of the cornerstones of American political philosophy for centuries. In the Internet era, there is no shortage of advice — certain, definitive and complete with authoritative-looking (and often misleading) sources — about what a civilian can and cannot do when interacting with an agent of the state.

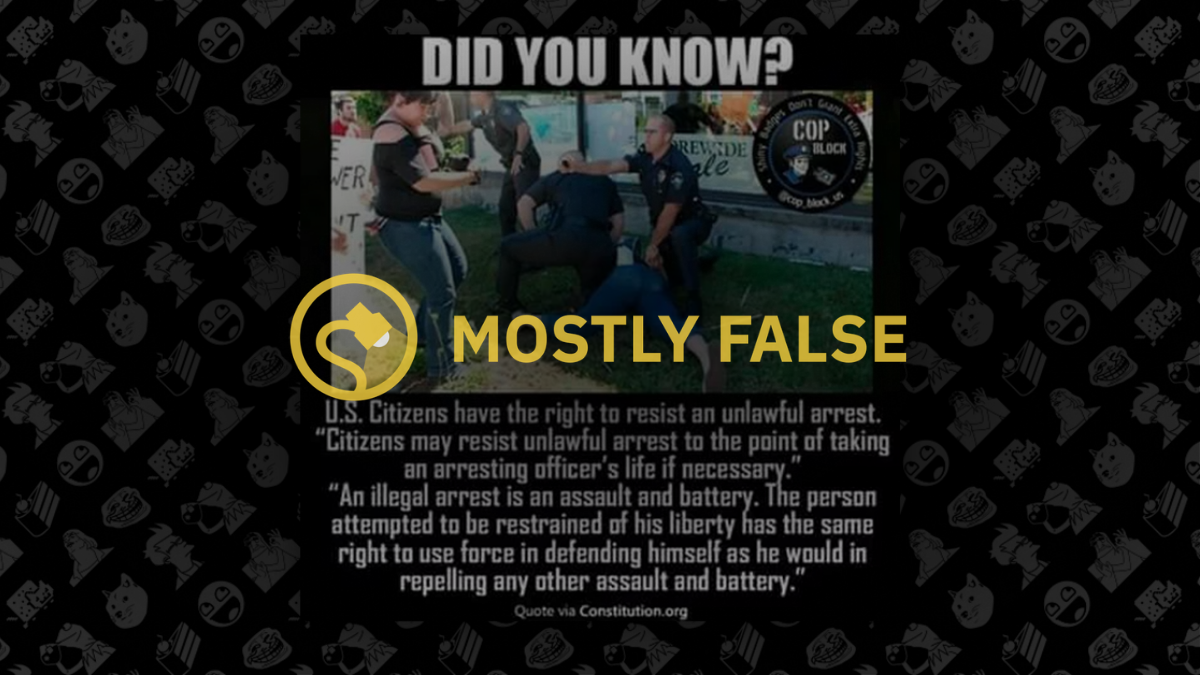

One common claim is that, contrary to conventional wisdom, individuals do in fact have a constitutional right to resist unlawful arrest. For example, the "Cop Block" Facebook page produced this meme:

Did you know? U.S. citizens have the right to resist an unlawful arrest. "Citizens may resist unlawful arrest to the point of taking an arresting officer's life if necessary."

"An illegal arrest is assault and battery. The person attempted to be restrained of his liberty has the same right to use force in defending himself as he would in repelling any other assault and battery."

The source for this claim is the web site Constitution.org, which is run by Jon Roland, a Texas computer scientist with links to the anti-government patriot and militia movements. In one entry, originally posted in 1996, Roland provides quotes from several different court cases, all designed to support the "unlawful arrest" argument. Among them are the two quotes included in the meme.

Here's the first, as outlined by Roland:

“Citizens may resist unlawful arrest to the point of taking an arresting officer's life if necessary.” Plummer v. State, 136 Ind. 306. This premise was upheld by the Supreme Court of the United States in the case: John Bad Elk v. U.S., 177 U.S. 529. The Court stated: “Where the officer is killed in the course of the disorder which naturally accompanies an attempted arrest that is resisted, the law looks with very different eyes upon the transaction, when the officer had the right to make the arrest, from what it does if the officer had no right. What may be murder in the first case might be nothing more than manslaughter in the other, or the facts might show that no offense had been committed.”

The first quote does not actually come from Plummer v. State, an 1893 case ruled on by the Indiana Supreme Court. However, Chief Justice James McCabe, in his written opinion, did support the right of an individual to forcibly resist an unlawful arrest, writing:

When a person, being without fault, is in a place where he has a right to be, [and] is violently assaulted, he may, without retreating, repel force by force, and if, in the reasonable exercise of his right of self-defense, his assailant is killed, he is justifiable. These principles apply as well to an officer attempting to make an arrest, who abuses his authority and transcends the bounds thereof by the use of unnecessary force and violence, as they do to a private individual who unlawfully uses such force and violence.

Roland correctly points out that seven years later, the United States Supreme Court unanimously granted a new trial in the case of a man sentenced to death for killing a police officer while resisting arrest (John Bad Elk v. United States, 1900.) This ruling was made on the basis that the trial judge had erred in law by telling the jury that the arrested man (John Bad Elk) had no right to resist arrest, regardless of whether there was a legal justification for his arrest.

An individual did have the right to resist an arrest, the court ruled, if there was no legal justification for that arrest. Importantly, the Supreme Court did not exonerate Bad Elk. It did not find that an individual has an absolute right to resist unlawful arrest, nor that any they should be free from criminal culpability for any harm they inflict on a police officer while resisting arrest.

This is in contrast to the Plummer case, where Justice McCabe described the act of killing a police officer while resisting an unlawful arrest as "justifiable." Indeed, John Bad Elk would have undergone a second murder trial, if he had not died in prison while waiting for it to begin.

Roland also discussed the second quotation included in the meme, which states "An illegal arrest is an assault and battery." This statement comes from a 1950 Maine Supreme Court case, which revolved around a violent altercation between a Deputy Sheriff named John Gallant and a man named Rodney Robinson, who had been convicted of assaulting Gallant while Gallant was arresting him.

In the course of his ruling, Chief Justice Edward F. Merrill wrote:

An illegal arrest is an assault and battery. The person so attempted to be restrained of his liberty has the same right, and only the same right, to use force in defending himself as he would have in repelling any other assault and battery.

However, Merrill qualified this significantly later in his written opinion, explaining that an individual only had a right to physically resist an unlawful arrest by using force proportionate to the force being used in the arrest. In other words, an individual had no right to physically assault a police officer who had only, up to that point, verbally informed them they were being arrested.

While it is true that a person who is illegally arrested may use such force as is reasonably necessary to resist the force used against him, he cannot initiate the use of force. We recognize that there are circumstances under which an assault may be repelled by a battery, and a show of force may be repelled by actual force. But words alone do not justify an assault. A mere statement by an officer that a person is under arrest, even if the officer has no authority to arrest, does not justify an attack by him on the officer before any physical attempt is made to take him into custody.

Over the second half of the 20th century, the right to resist unlawful arrest was progressively diluted and struck down in courtrooms and legislatures across the country, as documented in a 1997 paper by the lawyer and law professor Andrew Wright. In 1969, for example, Alaska Supreme Court Justice Roger Conner wrote:

We feel that the legality of a peaceful arrest should be determined by courts of law and not through a trial by battle in the streets. It is not too much to ask that one believing himself unlawfully arrested should submit to the officer and thereafter seek his legal remedies in court. Such a rule helps to relieve the threat of physical harm to officers who in good faith but mistakenly perform an arrest, as well as to minimize harm to innocent bystanders.

...We hold that a private citizen may not use force to resist peaceful arrest by one he knows or has good reason to believe is an authorized peace officer performing his duties, regardless of whether the arrest is illegal in the circumstances of the occasion.

According to Wright, by 1997 "the right [had] gone from the rule to the exception," something he attributed to four major factors and developments in criminal justice and the rights of the accused:

- "Improved jail conditions and the birth of procedural safeguards"

- "Preference for judicial resolution of the 'unlawfulness' of the arrest"

- "Difficulty in distinguishing between a 'lawful' and an 'unlawful' arrest"

- "The existence of alternative remedies"

In eighteenth-century England [where the concept emerged through landmark court cases] and in her fledgling colonies, a person wrongfully arrested did not enjoy any of the pretrial procedural rights that today a person takes for granted. Once arrested, a detainee could be confined for an indefinite period, often in deplorable conditions. The timetable for the trial of a defendant's case was uncertain at best. The absence of a formal arraignment prevented a defendant from learning of the charges that lead to his incarceration.

With the ratification of the Constitution and its Bill of Rights, forces were set in motion that would eradicate much of the rationale for maintaining this common-law right.

We checked the law on resisting arrest in all 50 states, and found only one — North Dakota — whose statute explicitly states that there is a legal defense against conviction for resisting arrest on the basis that the arrest was "not lawful." However, even in North Dakota the law stipulates that falsely believing the arrest was unlawful is not a defense. It also stipulates that an arrest is unlawful only if a police officer knowingly violates the law, as opposed to making a mistake in good faith.

In 14 states (Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Iowa, Maine, Massachussetts, Missouri, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas) the law explicitly states that the legality of the arrest, or an individual's beliefs about its legality, does not offer a defense against conviction for resisting arrest.

In 15 states (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Maryland, Mississippi, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, Wisconsin, Wyoming) the law states that it is a criminal offense to resist, specifically, a "lawful" or "authorized" arrest.

In those states, whether or not you are acting legally by resisting an unlawful arrest will depend on how the courts have interpreted the law, and in many cases there are still prohibitions on using physical force (especially disproportionate force) to resist even an unlawful arrest.

In the remaining 20 states, the law prohibits resisting an arrest, without any reference to the legality or illegality of the arrest.

In other words, in most of the United States there is absolutely no right to resist an unlawful arrest, and even in the minority of states where the law allows for the possibility of such a right, that right is limited. In practical terms, resisting an arrest — even one you believe to be unlawful — risks provoking a violent retaliation.