Since the middle of the last century, revolving doors have been a quietly ubiquitous feature of modern cities around the world. But do they have their origins in one man's neurotic attitude toward holding doors open for women?

The most often-cited example of this legend is a 2013 article in Slate by Roman Mars, of the design podcast 99% Invisible.

The story goes like this: Theophilus Van Kannel hated chivalry. There was nothing he despised more than trying to walk in or out of a building, and locking horns with other men in a game of “oh you first, I insist.” But most of all, Theophilus Van Kannel hated opening doors for women. He set about inventing his way out of social phobia.

In the accompanying podcast episode, Mars warned: "Keep in mind that with all these origin stories, when they sound a little too much like stories, they're probably not completely true."

David McCall, writing in the Australian Design Review four years later, also traced the invention to Van Kannel's purported misogyny:

The story goes that he invented the revolving door because he simply hated holding doors open for people, especially women. It has also been reported that Kannel [sic] was a man without a family. These two facts may not be unrelated.

The earliest version of the story that we could find was a 2008 post by Jaime Morrison on the art and design blog The Nonist, which went into considerable detail about the origins of Van Kannel's aversion to chivalry, tracing it back to a public spanking from his mother and attributing his invention to his wife's insistence that he hold open doors for her at all times.

It seems that when Van Kennel [sic] was a boy, still in the care of his mother but just on the cusp of cultural manhood, he found the lingering rules of chivalry rather bothersome. In particular he refused to accept that he was expected to open the door for women and allow them to cross the threshold before him.

A silly sort of quirk to our minds, certainly, but it was taken seriously enough by his mother that after numerous warnings and threats she eventually felt compelled to take action. Van Kennel [sic] family histories have it that at some point in his twelfth year she administered a savage bare-bottomed spanking, during a salon in the family’s drawing room, in full and explicit view of 37 local mothers and daughters.

...Had this been the only episode the world may have never had a revolving door to shuffle through. As it so happens, however, Theophilus Van Kennel [sic] married a woman who, though beautiful and slyly clever, had an odd and stubborn quirk of her own.

Young Abigail Van Kennel, it seems, refused to pass from one room of their apartments to another without the assistance of Theophilus.

That blog post contains the tongue-in-cheek disclaimer that "...All untruths are, I assure you, my own. I’ll leave it to you to sort out which is which"; and cites just one source, an essay by the MIT professor James Buzard -- which makes no mention of Van Kannel's now-legendary misogyny.

Indeed, despite extensive archival research, we did not find any evidence to back up the persistent rumor that Theophilus Van Kannel invented and refined the revolving door because of a neurotic aversion to holding doors open for women and others. In fact, we found several pieces of evidence which severely undermine the credibility of this claim.

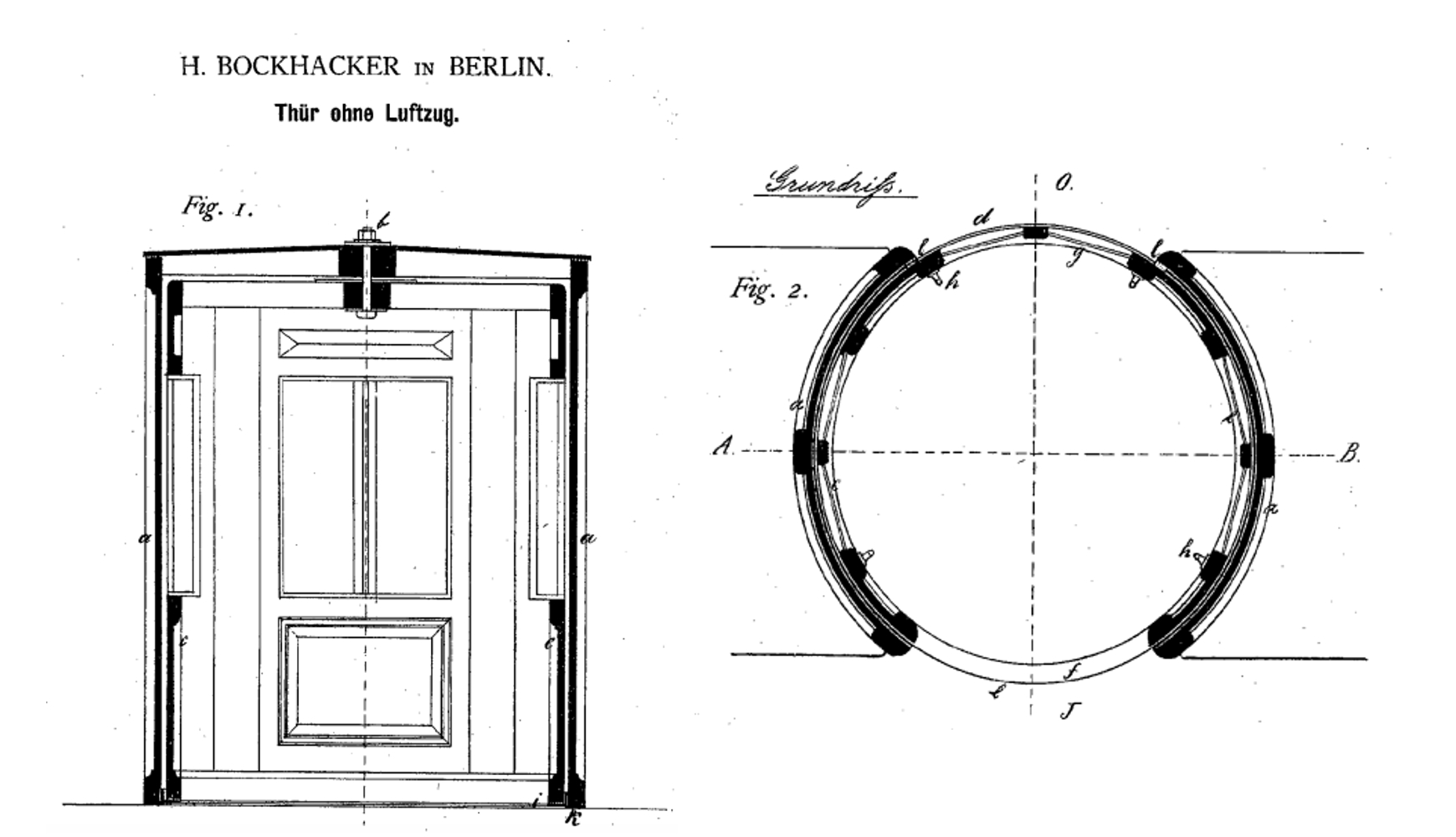

In July 1882, an H. Bockhacker received a patent in Berlin for a "Thür ohne Luftzug" ("draftless door") whose design is essentially that of a revolving door.

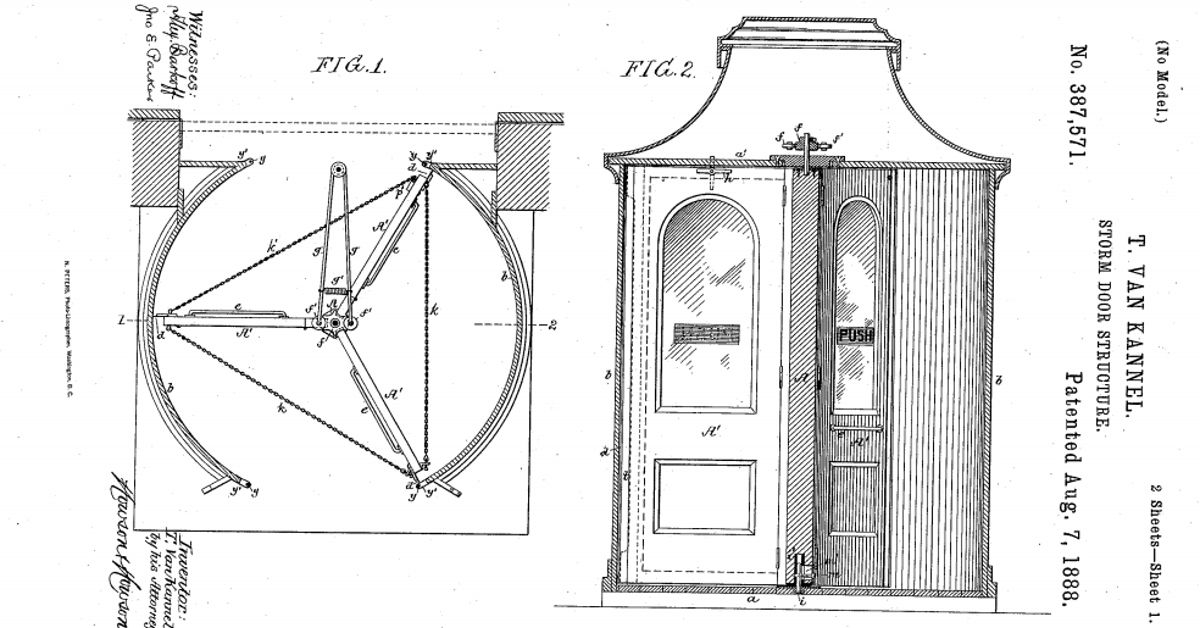

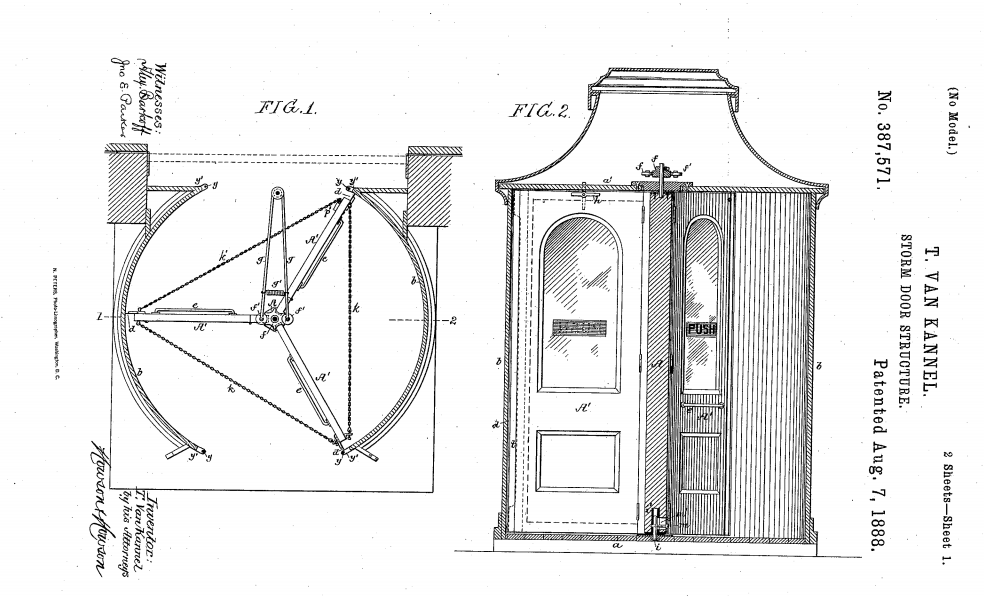

Six years later, on 7 August 1888, Theophilus Van Kannel of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania received Patent #387,571 for his "Storm Door Structure."

In his patent application, Van Kannel wrote:

It will be evident that a storm door structure of the character described possesses numerous advantages over a hinged-door structure of the usual character, for, as the door fits snugly in the casing, it is perfectly noiseless in its operation and effectually prevents the entrance of wind, snow, rain, or dust either when it is closed or when persons are passing through it. Moreover, the door cannot be blown open by the wind, as the pressure is equal on both sides of the center of motion.

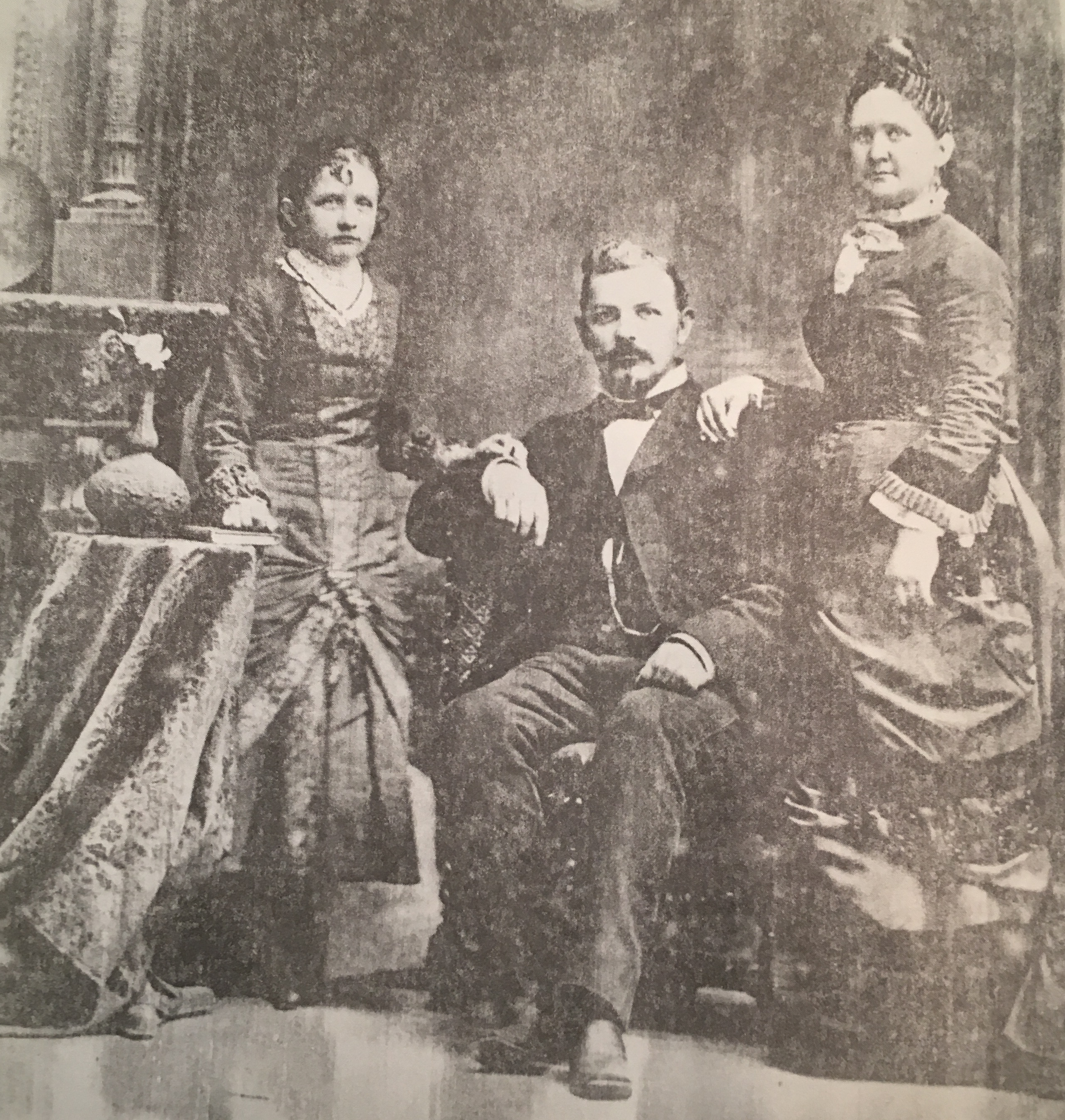

Van Kannel subsequently patented several refinements and improvements to the revolving door, founded the Van Kannel Revolving Door Company, and died in New York City on Christmas Eve, 1919, at the age of 78.

He was born in a log cabin in Coshocton County, Ohio, on 21 October 1841, to Swiss immigrant parents. Throughout his life, he was a prolific inventor.

A 1988 publication of his autobiography and journal, housed in the Library of Congress, lists 49 patents, but the book's editor writes that Van Kannel might have actually put his name to "about 75" of them.

Over the years, Theophilus invented a cherry stoner, cider mill, water hydrant, shipping tag, gas machine check-valve, a sewing machine, an "apparatus for scalding vegetable or fruit," and many more. He was also the inventor and owner of the Witching Waves ride at a Coney Island amusement park.

He married Amanda Clayton, of Chester, Illinois and in November 1867 the couple had a daughter named Lulu. This refutes David McCall's suggestion that Van Kannel's alleged misogyny was due to the fact that he did not have a family. He did. The fact that Van Kannel's wife was named Amanda also severely undermines The Nonist's colorful stories about his wife "Abigail," who "refused to pass from one room of their apartments to another."

In fact, Theophilus Van Kannel's two-volume, almost 500-page autobiography and journal does not contain any evidence of any neurosis relating to women, nor any social phobias of any kind. What it does reveal is a multi-talented young man, somewhat sober and straight-laced, who struggled for many years with debt and an artificial leg, but enjoyed a fairly healthy social life, combined with a consistent dedication to his work.

He wrote frequently to his mother, regularly visited his sister and her family, and spoke lovingly about his female relatives. (His journal entry on 30 January 1864 reads: "Letter from my sister requesting me to write an obituary for her husband. Sent $5 to mother.")

Another entry suggests Van Kannel understood and honored the Victorian norms of chivalry, without any reservations.

28 September 1861 (aged 19): ...I received permission to buy some window blinds for the schoolhouse. While in the post office a very old lady came in to send off a letter, but she had no money to pay for the stamp. She asked the postmaster, Mr Bowman, to credit her, but he refused. I then bought ten cents' worth of stamps and sent her letter. She was a stranger to me...

As he grew into his 20s, Van Kannel's journal shows him courting young women in Cincinnati, Ohio, all the while following the rules of chivalry and decorum.

26 February 1863 (aged 21): We all went to the church again this evening to practice our parts for the exhibition, and all showed great improvement. For the first time I mustered up enough courage to ask a young lady for her company home, and she very readily accepted.

Nothing in his journal suggests the kind of "social phobia" or misogyny involved in the many stories told about him 150 years later. He attended church every Sunday, taught children, attended school with men and women, was an active member of debating societies, met friends for dinner and drinks (although he disliked drunkenness), and occasionally escorted young women home or to the theater.

His interests and inventions were eclectic. By 1867 he was already developing a type of door spring, and so it's not at all surprising that he would turn his mind to the innovation that eventually became the revolving door.

Swinging doors let in drafts, making it difficult to control the temperature of a building, especially one with heavy footfall like a bank or train station. It is in keeping with the pattern of Van Kannel's professional life that he would have identified this problem, and attempted to solve it using his gift for engineering.

His invention of the revolving door does not require a psychological motivation. Nor were we able to find one, despite reading hundreds of pages of archival material and the journal of Theophilus Van Kannel himself. We looked at several news and feature articles about Van Kannel, some dating to the early 20th century. Not one mentioned Van Kannel's now-mythical misogyny or aversion to chivalry -- until The Nonist post, the veracity of which is extremely questionable.

We contacted the 99% Invisible podcast, but we did not receive a reply by publication time.

In October 2018, we received an email from Jaime Morrison, creator of the Nonist blog and author of the 2008 article about Theophilus Van Kannel and the invention of the revolving door. Morrison told us that he had written about Van Kannel's now-legendary misogyny as no more than a joke which he was disappointed to find had been taken seriously by others:

I just wanted to confirm that yes, the piece was in fact a humor piece, and that yes the chivalry aspect of the story was a total fabrication...When I wrote the piece I assumed that the absurdity of the idea would be self-evident, and even hedged by including the disclaimer which [you quoted]. Alas, that old chestnut about assumptions proved its inherent wisdom yet again.