A favorite bit of annoying trivia is for someone to ask who the 12th President of the United States was, chortle when the respondent answers "Zachary Taylor," proclaim that the 12th President was really David Rice Atchison, and then chortle again when the respondent's expression indicates they never heard of any such person.

The basis for this routine is that President-elect Zachary Taylor was set to succeed James K. Polk and be inaugurated as the 12th President of the United States on March 4, 1849. However, March 4 fell on a Sunday, and Taylor declined to hold his inauguration on the Sabbath, so his swearing-in was deferred for a day. Now, over one hundred and seventy years later, a ubiquitous bit of presidential apocrypha holds that someone else served as president during the twenty-four hour period between the expiration of Polk's term and the inauguration of Taylor. A plethora of trivia reference sources state that U.S. Senator David Rice Atchison of Missouri was (or acted as) president for that one day, but claims placing him in that office are really nothing more than "What if?" fantasies based on erroneous assumptions and interpretations.

The office of President of the United States was established by the ratification of the Constitution of the United States of America in 1788. Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution reads (in part):

The executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. He shall hold his office during the term of four years, and, together with the Vice President, chosen for the same term, be elected, as follows:

In case of the removal of the President from office, or of his death, resignation, or inability to discharge the powers and duties of the said office, the same shall devolve on the Vice President, and the Congress may by law provide for the case of removal, death, resignation or inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what officer shall then act as President, and such officer shall act accordingly, until the disability be removed, or a President shall be elected.

Before he enter on the execution of his office, he shall take the following oath or affirmation: — "I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States."

Also, Article I, Section 3 established the vice president as the President of the Senate:

The Vice President of the United States shall be President of the Senate, but shall have no vote, unless they be equally divided.

The question of deciding who should act as president if something should happen to both the chief executive and the vice president was left to Congress to decide at a later date. It didn't take long: In 1792 Congress passed a Presidential Succession Act which provided that after the president and vice President, the president pro tempore of the Senate (i.e., the person selected to preside over the Senate whenever the Vice-President was absent) would act as president. If the Senate had not designated a president pro tempore, then the speaker of the House of Representatives would fill in, and the line of succession would then proceed through the cabinet officers in the order their departments were created.

About a century later, the Presidential Succession Act came under renewed scrutiny. The custom of the Senate had been to select a president pro tempore only when the vice president was absent, and thus for long stretches of time (especially since Congress did not sit in session all year around) the Senate had no president pro tempore. Additionally, the Presidential Succession Act raised the distinct possibility that a member of the opposition party might assume the presidency. The Senate had been relying upon a gimmick under which the vice president would voluntarily leave the Senate chamber just before the end of a session so that a president pro tempore could be named before adjournment, but not all vice presidents were willing to play along (especially when the opposition was the majority party). Accordingly, in 1886 Congress passed a new Presidential Succession Act, one which removed the president pro tempore of the Senate and the speaker of the House of Representatives from the line of succession. After 1886, cabinet officers, in the order their departments were created, were next in line for the presidency after the president and vice president.

Things changed again sixty years later. Vice President Harry S. Truman had ascended to the White House upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt two years earlier, and as the United States no longer had a vice president, the possibility that the office might fall to someone further down the line of succession was a very real one. Truman felt that the first few persons in line for the presidency should be "elected representatives of the people" (rather than cabinet officers appointed by the president), so the Presidential Succession Act of 1947 restored the president pro tempore of the Senate and the speaker of the House of Representatives to the line of succession, albeit in reverse order (possibly because the current president pro tempore was no friend of Truman's, but the speaker of the house was a long-time ally of his).

After that introduction, we now turn to the events of 1849. The terms of the incumbent president and vice president had expired on March 4, but the new president and vice president weren't sworn in until the following day. So who was president for the day in between those two events?

The law in effect in 1849 was the Presidential Succession Act of 1792, which specified that the president pro tempore of the Senate was next in line for the White House after the vice president. The Thirtieth Congress had, just before adjourning on March 3, 1849, selected Missouri senator David Rice Atchison to continue as President Pro Tempore, so he is the person now tagged as having been "President for a Day" between March 4 and March 5 of 1849. But was he really?

Atchison wasn't considered to have served as President back in 1849, and a number of legal arguments preclude our retroactively assigning him this curious honor.

1) The Constitution granted Congress the power of "declaring what officer shall then act as President" in the "case of removal, death, resignation or inability, both of the President and Vice President." It didn't say Congress could declare someone to actually be the president, only someone to act as the president. This might be considered a distinction without a difference or mere semantic trickery, but when John Tyler became the first vice president to be elevated to the office of president upon the death of William Henry Harrison in 1841, Tyler was dubbed "His Accidency," and many critics questioned whether he was legally president or merely someone empowered to "discharge the powers and duties of the said office" until the next election. Tyler firmly established that he was to be regarded as a "real" president, but that tradition was not established by law until the passage of the twenty-fifth amendment to the Constitution in 1967, which stated: "In case of the removal of the President from office or of his death or resignation, the Vice President shall become President."

2) Even if we overlooked the distinction between someone empowered to "act" as president and a "real" president, the Constitution still poses some problems for David Rice Atchison's claim to the presidency. As noted above, the Constitution stated that "Congress may by law provide for the case of removal, death, resignation or inability, both of the President and Vice President, declaring what officer shall then act as President." None of the cases specified in this clause had occurred in 1849: neither the outgoing president nor vice president had died, resigned, been removed from office (i.e., through impeachment), or was "unable" to fulfill the duties of his office, and the same was true of the incoming president and vice president. The incoming president simply deferred his inauguration for one day, so none of these cases occurred, the Presidential Succession Act of 1792 wasn't applicable, and no one was next in line of succession.

3) If we dismissed the previous argument by claiming that the outgoing president indeed had been "removed" from office (or was "unable" to continue in office) because his term had expired, we have to consider that in 1849 the Constitution didn't specify exactly when a president's term expired. It merely stated that the President "shall hold his office during the term of four years"; it didn't say his term expired exactly four years from the date of his inauguration, at precisely the same hour as his swearing-in. Not until 1933 was the Constitution amended to specify the date and time at which a president's term expires:

Amendment XX (1933)

Section 1. The terms of the President and Vice President shall end at noon on the 20th day of January, and the terms of Senators and Representatives at noon on the 3d day of January, of the years in which such terms would have ended if this article had not been ratified; and the terms of their successors shall then begin.

(The incoming vice president is always sworn in before the incoming president, and sometimes this swearing-in doesn't take place until after noon, but nobody has ever seriously claimed that vice presidents technically "become" president during the brief interludes between their inaugurations and those of the incoming presidents. Also, re-elected incumbent presidents (such as James Monroe in 1821) have occasionally deferred being sworn in for their second terms when their inaugural days fell on Sunday, but nobody claimed the U.S. went without a president for one day on those occasions.)

4) The Constitution says that before the president-elect "enter on the execution of his office, he shall take the following oath or affirmation ..." That document doesn't say the president-elect has to take the oath before becoming president; merely that he must take the oath before executing the duties of the presidency. Whether a real distinction exists here is something that has never been tested, but we suspect that if, for example, the president were killed during a nuclear attack by a hostile foreign power, the cabinet and the military wouldn't stand around waiting for the vice president to be sworn in before accepting his orders.

In all of the above sounds like legal nit-picking, consider the more substantial reasons why David Rice Atchison could not possibly have been considered President of the United States, however briefly.

Atchison was no longer President Pro Tempore of the Senate at the time of Taylor's scheduled swearing-in on March 4, 1849. Atchison was voted into that role during the Thirtieth Congress, but the Thirtieth Congress had adjourned for the last time on March 3, and it (along with Atchison's first term in the Senate) ended on March 4. The role of president pro tem does not carry over from one Congress to the next, so when Taylor was due to be sworn in, neither Atchison nor anyone else held that position.

More important, though, is that Atchison's claim to a one-day presidency is based on the technicality that even though Zachary Taylor had been duly elected president for a term slated to begin on March 4, 1849, Taylor didn't actually become president until the moment he was sworn in on March 5. But since Atchison was never sworn in as president either, he never held that position, even for a moment.

The plain truth is, it's difficult to find one valid reason why David Rice Atchison should be considered to have served as "President for a Day." No one considered him to be president at the time, and Atchison himself later told a St. Louis Globe-Democrat reporter that there had been no president at all that Sunday. Atchison stated that on his alleged one day as President: "I went to bed. There had been two or three busy nights finishing up the work of the Senate, and I slept most of that Sunday."

The matter wasn't given much thought at all at the time, and the possibility that the U.S. had been without a president for one day didn't really occur to anyone until years later. Then, in retrospect, someone took a glance at the rules of succession and mistakenly assumed that, if a one-day gap in the presidency had really occurred, Atchison should have been the one to fill it.

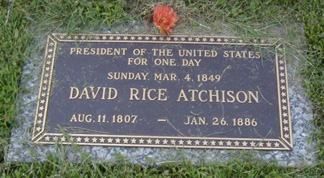

Nonetheless, Atchison's gravestone in Plattsburg, Missouri, as well as a nearby statue of him, bear inscriptions falsely identifying him as "President of the United States for One Day":