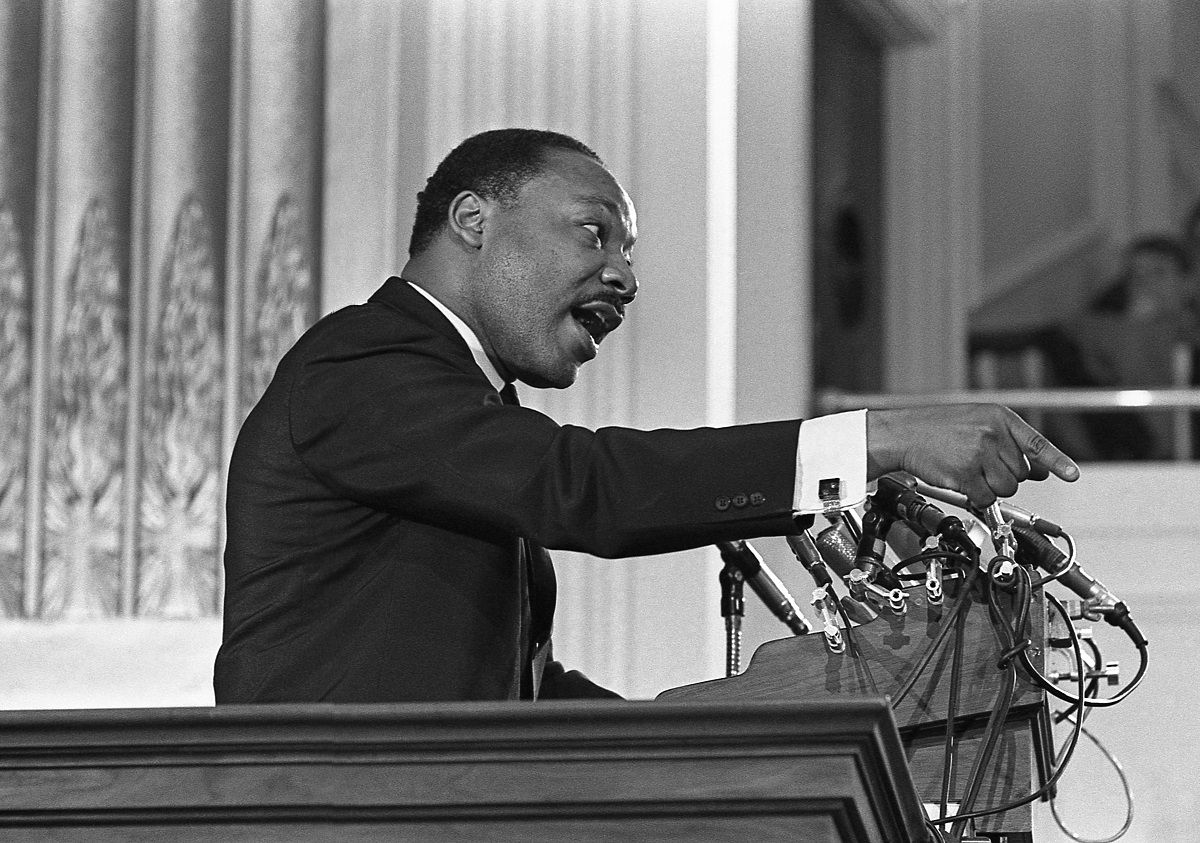

One of the many topics that civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. often touched upon in his public statements and private letters was his viewpoint that the impoverished in America were being poorly served by capitalism, and that the resources needed to ameliorate poverty were abundantly available but inequitably distributed. The following quotations are but a few examples of King's statements on the topic:

“And one day we must ask the question, ‘Why are there forty million poor people in America? And when you begin to ask that question, you are raising questions about the economic system, about a broader distribution of wealth.’ When you ask that question, you begin to question the capitalistic economy. And I’m simply saying that more and more, we’ve got to begin to ask questions about the whole society ..."

“You can’t talk about solving the economic problem of the Negro without talking about billions of dollars. You can’t talk about ending the slums without first saying profit must be taken out of slums. You’re really tampering and getting on dangerous ground because you are messing with folk then. You are messing with captains of industry. Now this means that we are treading in difficult water, because it really means that we are saying that something is wrong with capitalism.”

One quote meme circulated via social media attributes the following similar statement to King:

"Capitalism does not permit an even flow of economic resources. With this system, a small privileged few are rich beyond conscience, and almost all others are doomed to be poor at some level. That’s the way the system works. And since we know that the system will not change the rules, we are going to have to change the system."

Although this quotation is congruent with other documented expressions by King on the subject of capitalism, it is not found in any of his writings, nor in any transcripts of his speeches or public statements.

This quotation originated with a reminiscence published in "My Song," the 2011 memoir of singer/actor Harry Belafonte. In that memoir, Belafonte — who had first met King in 1956 — described his last meeting with the civil rights leader, which took place at Belafonte's apartment in New York on March 27, 1968, just a week before King was assassinated in Memphis:

A party was held at Belafonte’s large apartment. After the guests had left, King and some of his closest colleagues stayed and talked about the conditions in the country and the state of the civil rights movement. Among those present, in addition to King and Belafonte, were King’s lawyer, Clarence Jones, his secretary and bodyguard, Bernard Lee, and Andrew Young, who would later become a congressman, the mayor of Atlanta, and also the US ambassador to the United Nations under President Jimmy Carter.

During that after-party talk, Belafonte wrote, the following conversation took place:

As usual, Martin was late. He always packed too much into his schedule, trying to do it all. This time a stop in Newark, New Jersey, had left him shaken. He'd met with Amiri Baraka, better known as LeRoi Jones, the playwright, essayist, and poet, who had formed a group called New Ark. Baraka identified himself as a black nationalist, and now openly advocated violence. He'd been arrested for carrying a gun during the previous summer's riots in Newark, and with his new group he was threatening to disrupt the city again. Martin had tried to reason with him, with no success. Baraka and his followers had denounced Martin bitterly. They'd scoffed at nonviolence, and vowed to tear Newark down in a matter of days. Martin was concerned that if Newark did blow, it would distract attention from the Poor People's Campaign and much that the movement had already accomplished.

None of this, however, Martin revealed when he walked in, because our gathering included journalists -- The New York Times's Tom Wicker and Anthony Lewis, among them. He wanted to stay on point, not muddy the message. As on the eve of Birmingham, we wanted to see media interest as much as raise money. I sensed Martin's mood, but saw him push it away. Instead, with all the passion he could muster, he talked up the Poor People's Campaign. Only when the journalists and paying guests had left did Martin let his feelings show with the inner circle who remained.

Bernard Lee, Martin's personal secretary and bodyguard, was there that night; he was never far from Martin's side. So was Andrew Young, the future mayor of Atlanta. Stan Levinson was long since back in the circle; his exile had ended when Bobby Kennedy stepped down from being Attorney General. Clarence Jones, Martin's lawyer and another of his closest confidants, was there. [My wife] Julie was there, too, her feet tucked up under her, a glass of vodka in her hand. Her opinions were sought and valued whenever the group met in our apartment.

Martin poured his customary Bristol Cream, but skipped the routine of seeing how much remained. His collar open, his shoes off, he sipped pensively at the oak bar, Andy [Young] and Stan and Clarence on either side of him, me as host behind the bar. At first, Martin stayed on the subject of the evening. He spoke so quietly that Bernard, lying on a sofa behind him, soon fell asleep. But as he talked about Washington, and what he hoped to accomplish, be grew increasingly agitated.

"What bothers you, Martin?" I asked. "What's got you in such a surly mood?"

"Newark," Martin said, and proceeded to tell us of his unnerving visit with Amiri Baraka. "Beyond what an eruption in that city would mean, how it would take us off-course. I'm just so disturbed at what I'm hearing more and more. Somehow, frustration over the [Vietnam] war has brought forth this idea that the solution resides in violence. What I cannot get across to these young people is that I wholly embrace everything they feel! It's just the tactics we can't agree on. I have more in common with these young people than with anybody else in this movement. I feel their rage. I feel their pain. I feel their frustration. It's the system that's the problem, and it's choking the breath out of our lives."

In the pause that followed, Andy replied, "Well, I don't know, Martin. It's not the entire system. It's only part of it, and I think we can fix that."

Suddenly, Martin lost his temper. "I don't need to hear from you, Andy," he said. "I've heard enough from you. You're a capitalist, and I'm not. And so we don't see eye to eye -- on this and a lot of other stuff."

It was an awkward moment. Martin was really angry. But I understood the subtext. Deep down, Andy was ambivalent about the Poor People's Campaign. All the other goals that we had set for ourselves up to this moment were tangible. Almost all of them were focused on justice. But when it came to economics, the goals were more complicated, the lines more blurred. Andy didn't believe that all the victims came from the same level of experience. He felt that there was a critical difference between poor whites and Hispanics, on one hand, and poor blacks on the other. This disparity, he felt, could make the Poor People's Campaign a rocky journey.

The tension peaked. "The trouble," Martin went on, "is that we lived in a failed system. Capitalism does not permit an even flow of economic resources. With this system, a small privileged few are rich beyond conscience and almost all others are doomed to be poor at some level." Taking a sip from his glass, he continued, "That's the way the system works. And since we know that the system will not change the rules, we're going to have to change the system."

We find little reason to doubt the substance of this quotation, as Belafonte was undeniably a friend and associate of King's, he related the circumstances surrounding the conversation with King in a detailed, first-person account, and the words he quoted are consistent with thoughts King expressed on many other occasions.

However ... human memory is a fragile thing, and we have to consider how accurately Belafonte (the sole source for this quote) might have reproduced King's words when relating them in his memoir more than 40 years later -- especially given that by Belafonte's own admission, news reporters and others who might have taken note of King's words that evening had departed before King made the statement in question. Does this passage describe a reconstruction of events made from personal memory long after the fact, or was the event documented at the time it occurred in some other form?

We've sent an inquiry to Belafonte's co-author, Michael Shnayerson, to see if he can shed any light on the nature of this recounting and will update this page accordingly if additional information becomes available.