In the 18th century, visitors to the London zoo didn't need to bring any money for admission. Rather, they could gain entrance to the exhibit by bringing a dog or cat to feed to the lions. That, at least, is the claim in one popular internet meme:

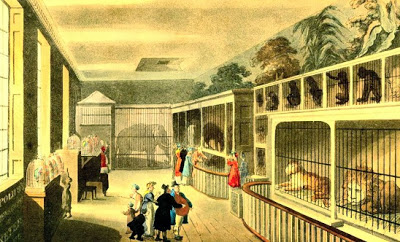

While we have not been able to definitively prove that zoogoers in the 18th century commonly fed stray animals to the lions in order to gain admission, this claim is at certainly plausible and originated with at least one credible source. It should be noted, however, that the "London Zoo" wasn't founded until 1826. The above-displayed meme is referring to the Royal Menagerie, a collection of exotic animals that were kept at the Tower of London between the 13th and 19th centuries.

The above-displayed meme was created by Factourism.com and repeats a rumor that has been published by a number of websites. The Londonist, for example, wrote in 2020:

"Under Elizabeth I, the public was allowed into the menagerie for the first time. Admission came at a price, albeit with a cruel caveat: it was free if you bought a dog or cat to feed to the lions."

Again, there weren't any "zoos" in London in the 18th century, so the meme could only be referring to the Royal Menagerie. According to London's Historic Royal Places, the first animals at the Royal Menagerie were three leopards (which may have actually been lions) that were gifted to King Henry III by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in 1235.

This "zoo" didn't really resemble the institutions that we have today. The Tower of London wasn't designed with the intent of housing hundreds of animals and caretakers weren't trained to take care of these exotic animals. The living conditions for the animals were poor at the Royal Menagerie, to say the least, and many of them did not survive long:

The King of France sent an elephant to the Tower in 1255, and Londoners flocked ‘to see the novel sight’.

Although the elephant had a brand new 40 foot by 20 foot elephant house and a dedicated keeper, it died after a couple of years.

Many of the other animals did not survive in the cramped conditions, although lions and tigers fared better, with many cubs being born.

While the conditions at the menagerie improved over the years, it doesn't seem to be much of a stretch to think that a stray dog or cat would have been fed to the lions. In fact, Wilfrid Blunt wrote in his 1976 book "The Ark in the Park: The Zoo in the Nineteenth Century" that that's exactly what happened. Blunt writes:

Over the years the Tower menagerie had its ups and downs, flourishing only when a monarch (or his consort) was interested in animals, or upon the chance receipt of rarities as gifts from foreign potentates. In 1436 there was not a single lion left; but nine years later, after Henry VI's marriage to the zoophile Margaret of Anjou, there were enough to justify the appointment of a Keeper of the Royal Lions. Under Edward IV the lions were removed to a spot just beyond the present Lion Gate.

[...]

In the eighteenth century the public was admitted to the Tower menagerie on the payment of three-halfpence or, alternatively, the provision of a cat or dog to be fed to the lions.

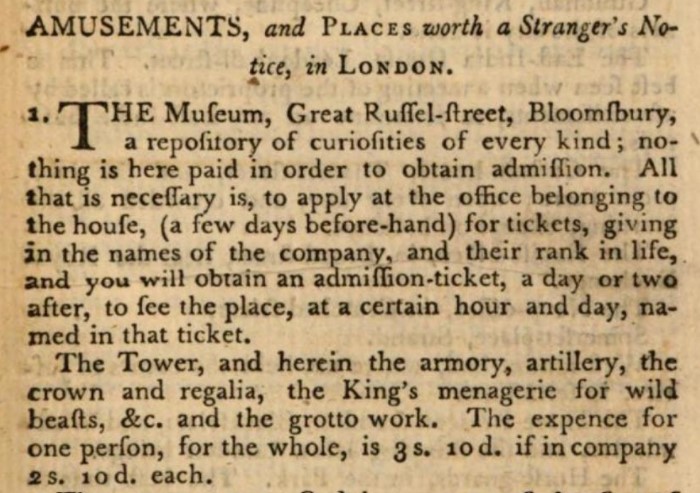

While it certainly seems plausible that patrons brought dogs and cats to feed to the lions in exchange for their admission (even if just a few times during this zoos multi-century existence), we were not able to find any contemporaneous evidence to support this claim. In fact, a guide of attractions around London published in 1776 mentioned the (monetary) admission price to see the "wild beasts" of the King's menagerie. This guide did not advise about bringing animals to feed the lions.

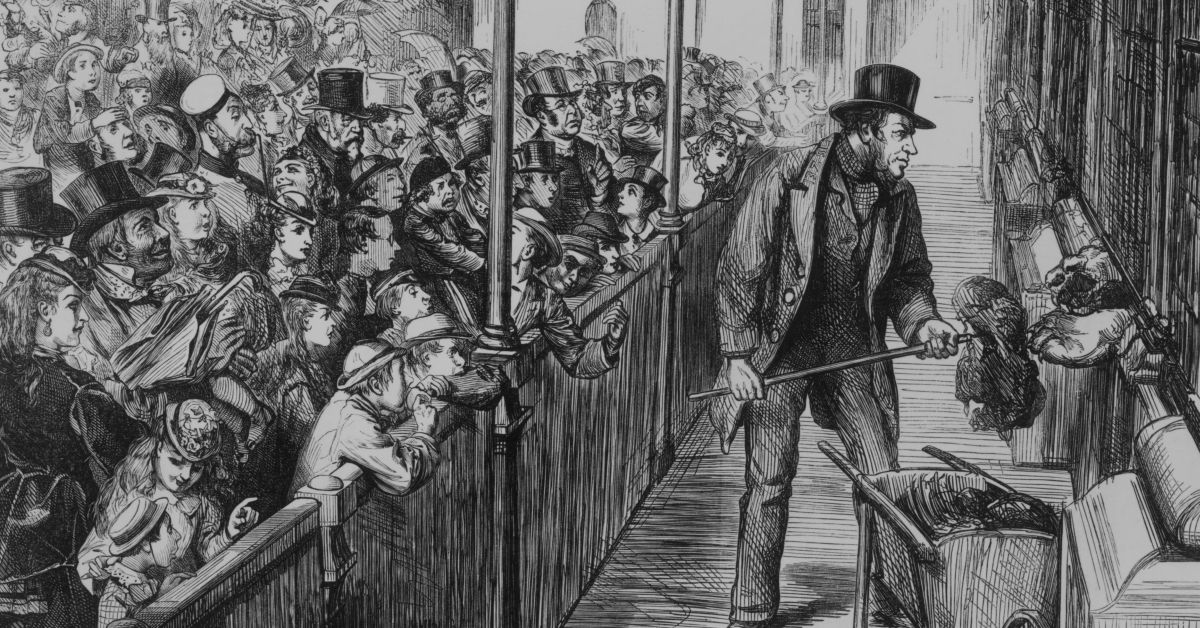

While we have not found any documents from the 1700s advertising a dog for ticket exchange, we did find a number of anecdotes about how animals fights were a big attraction. Blunt writes in his book about one incident 1764 in which the Duke of Cumberland pitted a tiger against a fine stag (or young horse). The stag apparently won the fight, was given a collar, and was then issued its freedom. Blunt described another incident in 1875 in which a traveling menagerie pitted a lion against a group of mastiffs. The Paris Review writes:

Lions were a big hit in the English court, even if no one really knew what to do with them. (In some cases, observers weren’t sure if they were lions at all. Later accounts suggest early lions were actually leopards.) Their treatment was predictably and heart-wrenchingly cruel: In 1240, the keeper William de Botton was given fourteen shillings to buy “chains and other things” that limited in-cage movement. Around the same time the cats were moved to a two-story “Lion Tower” where their movements were restricted to cramped enclosures, upstairs in daylight, downstairs at night. A few centuries later, James I would construct a platform from which he and his pals could watch staged fights between lions and dogs.

While lions at the Royal Menagerie were, on occasion, fed cats or dogs, we haven't found any definitive proof that this was a regular practice that involved donations from patrons. We reached out to the Historic Places of London, and we will update this article if more information comes available.