Lincoln approved the execution of 39 Dakota men convicted by a military commission of perpetrating massacres during the Dakota War of 1862.

The military commission had sentenced 303 Dakota fighters to death, but Lincoln commuted 264 of those sentences despite threats of mob violence and intense pressure to reverse his decision.

In March 2018, thousands of Facebook users shared a meme which asserts that President Abraham Lincoln had ordered the executions of 38 Native American warriors in 1862:

That claim is largely accurate, but it's also misleading; it omits to mention that although Abraham Lincoln did approve 39 death sentences (one of the condemned men was ultimately spared), he also prevented the hangings of 264 other Native Americans by commuting their death sentences, in the same order. It also fails to make it clear that the death sentences did not originate with Lincoln. Rather, the executions were ordered by a military commission and sent to the president, who had the legal authority to approve or decline to approve any or all of the sentences.

The Dakota War of 1862 involved a violent uprising by Dakota Sioux tribal members in Minnesota in response to hunger and privation as well as treaty violations on the part of the United States federal government, which had a long history of displacing and exploiting Native American peoples since the birth of the American colonies.

The conflict began in August 1862, lasted for six weeks, and involved killings, atrocities, and hostage-takings on both sides. On 26 September 1862, the Dakota surrendered at what became known as Camp Release in Minnesota. According to the Minnesota Historical Society, the U.S. forces then commenced military trials for hundreds of captured Dakota fighters:

On September 28, 1862, two days after the surrender at Camp Release, a commission of military officers established by Henry Sibley began trying Dakota men accused of participating in the war...

As weeks passed, cases were handled with increasing speed. On November 5, the commission completed its work. 392 prisoners were tried, 303 were sentenced to death, and 16 were given prison terms.

On 9 November 1862, the list of the 303 condemned Dakota fighters was sent to Lincoln for his approval of their executions. Two days later, he requested a review of their cases and trials.

In July 1862, the United States Congress had passed a law relating to court martials and military commissions which made it clear that death sentences emerging from such trials could not be carried out without the approval of the President of the United States:

...Be it further enacted that the President shall appoint, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, a judge advocate general, with the rank, pay, and emoluments of a colonel of cavalry, to whose office shall be returned, for revision, the records and proceedings of all courts-martial and military commissions, and where a record shall be kept of all proceedings had thereupon.

And no sentence of death, or imprisonment in the penitentiary, shall be carried into execution until the same shall have been approved by the President.

In a major 1990 paper on the trials and executions, University of Minnesota law professor Carol Chomsky was highly critical of the trials and of Lincoln's confirmation of the execution of the Dakota fighters for actions taken in the context of a military conflict, a punishment that was not handed down to other military combatants, such as Confederate soldiers in the Civil War.

However, she also noted that Lincoln was under intense pressure to sign off on the executions of all 303 Dakota men, and that a mob in Minnesota, stoked by local political leaders, threatened to implement vigilante justice should the president spare any of the condemned fighters:

[Major General John Pope] warned [Lincoln] that the people of Minnesota, perhaps combined with some of the soldiers, would take matters into their own hands and kill "all the Indians — old men, women, and children," if the President did not allow all the executions to go forward.

If the President proved reluctant to decide, he suggested, the condemned could be turned over to the state government. Minnesota Governor Ramsey left no doubt what decision he would make if given the opportunity, writing to Lincoln to urge execution of all the condemned. A great public outcry arose in Minnesota in response to reports that Lincoln might not carry out the full sentence of the military commission. The Stillwater, Minnesota Messenger demanded extermination of the Dakota: "DEATH TO THE BARBARIANS! is the sentiment of our people."'

Minnesota's Senator Morton Wilkinson and Representatives Cyrus Aldrich and William Windom wrote to Lincoln reciting stories of rapes and mutilation "well known to our people" and protesting any decision to pardon or reprieve the Dakota. If the President did not permit the executions, they said, "the outraged people of Minnesota would dispose of these wretches without law. These two peoples cannot live together. We do not wish to see mob law inaugurated in Minnesota, as it certainly will be, if you force the people to it."

In December 1862, Lincoln announced his decision about the issue to the United States Senate, suggesting that the priority of executions should be directed at captives who had committed acts of rape:

Anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other, I ordered a careful examination of the records of the trials to be made, in view of first ordering the execution of such as had been proved guilty of violating females.

However, the president discovered that only two of the 303 men had been convicted of rape, and so he widened the criteria for execution to those who had committed "massacres" (as opposed to just taking part in "battles"):

This class numbered forty, and included the two convicted of female violation. One of the number is strongly recommended by the commission which tried them for commutation to ten years' imprisonment. I have ordered the other thirty-nine to be executed on Friday, the 19th ...

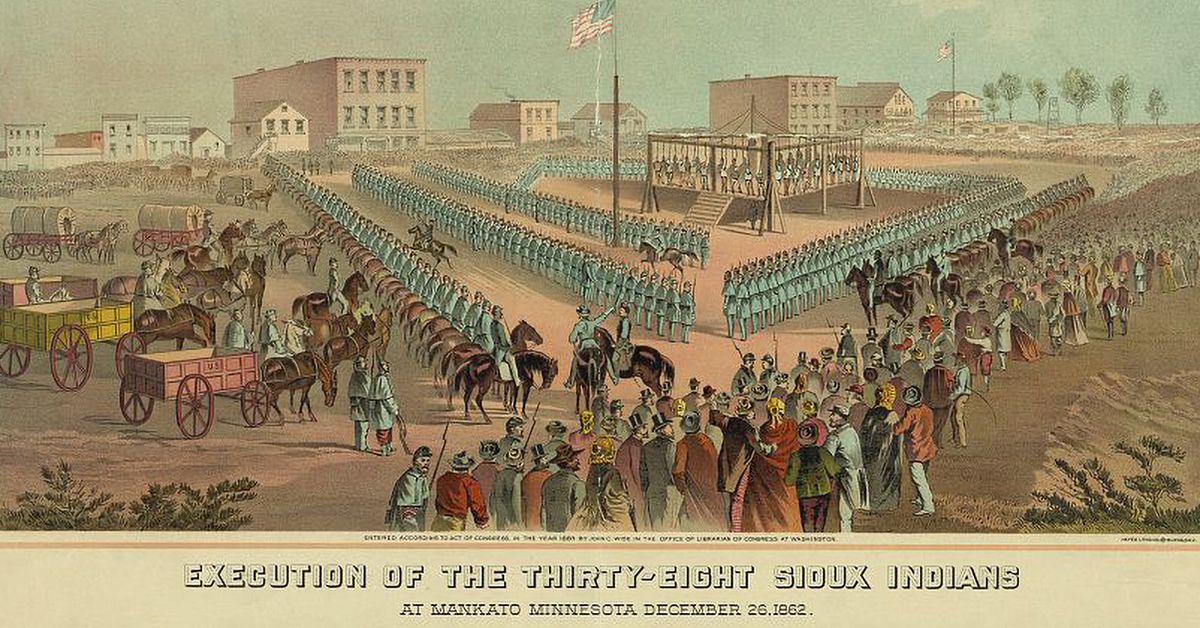

In the end, one of the 39 condemned men had his death sentence commuted, and the executions of the remaining 38 Dakota fighters took place on 26 December 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota:

A few weeks later, the New York Times offered a harrowing and disturbing account of those executions:

Precisely at the time announced — 10 A.M. — a company, without arms, entered the prisoners' quarters to escort them to their doom. Instead of any shrinking or resistance, all were ready, and even seemed eager to meet their fate. Rudely they jostled against each other, as they rushed from the doorway, ran the gauntlet of the troops, and clambered up the steps to the treacherous drop.

As they came up and reached the platform, they filed right and left, and each one took his position as though they had rehearsed the programme. Standing round the platform, they formed a square, and each one was directly under the fatal noose. Their caps were now drawn over their eyes, and the halter placed about their necks. Several of them feeling uncomfortable, made severe efforts to loosen the rope, and some, after the most dreadful contortions, partially succeeded.

The signal to cut the rope was three taps of the drum. All things being ready, the first tap was given, when the poor wretches made such frantic efforts to grasp each other's hands, that it was agony to behold them. Each one shouted out his name, that his comrades might know he was there. The second tap resounded on the air. The vast multitude were breathless with the awful surroundings of this solemn occasion. Again the doleful tap breaks on the stillness of the scene.

Click! goes the sharp ax, and the descending platform leaves the bodies of thirty-eight human beings dangling in the air. The greater part died instantly; some few struggled violently, and one of the ropes broke, and sent its burden with a heavy, dull crash, to the platform beneath. A new rope was procured, and the body again swung up to its place. It was an awful sight to behold. Thirty-eight human beings suspended in the air, on the bank of the beautiful Minnesota; above, the smiling, clear, blue sky; beneath and around, the silent thousands, hushed to a deathly silence by the chilling scene before them, while the bayonets bristling in the sunlight added to the importance of the occasion.

It is accurate to say that Lincoln approved the executions of 39 Dakota fighters, and that despite their convictions for participating in war-time massacres, the condemned men were not afforded the conventional rights of due process (such as trial by jury) and did not have attorneys present to plead on their behalf. It is also true that Lincoln, as President of the United States, did have the legal authority to commute all 303 death sentences presented to him for his approval.

However, in the very act of approving 39 executions, Lincoln was at the same time ordering the commutation of 264 death sentences. Despite intense political and popular pressure, Lincoln spared the lives of many more Dakota fighters than he condemned, albeit not as many as he could have. The popular meme displayed above leaves out this very important context, and it therefore gives an incomplete and misleading account of Lincoln's December 1862 decision.

Sources

Chomsky, Carol. "The United States-Dakota War Trials: A Study in Military Injustice." Stanford Law Review. Vol. 43 Issue 13. 1990.

Lincoln, Abraham. "Message to the Senate Responding to the Resolution Regarding Indian Barbarities in the State of Minnesota." Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. 11 December 1862.

The New York Times. "The Indian Executions -- An Interesting Account from Our Special Correspondent." 11 January 1863.

United States Congress. "37th Congress, Session 2, Chapter 201, Section 5." United States Congress. 17 July 1862.