The introduction of new EMV (Europay, MasterCard, and Visa) technology has enhanced the security of debit and credit card transactions by replacing standard cards with ones embedded with small computer chips that’s extremely hard to counterfeit. The addition of the chips makes the cards much harder to counterfeit and provides for additional authentication and security during point-of-sale transactions.

The manner in which EMV cards are physically handled during a sales transaction is somewhat different than with older cards, however. Rather than being swiped through a point-of-sale (POS) terminal, EMV cards are inserted (or "dipped") into the terminal and left in place for the entire transaction so that the reader and card can talk back and forth.

EMV cards can be either swiped or dipped (since not all merchants are yet set up with EMV-compliant card readers), and that duality has led to some confusion among consumers about whether liability for fraudulent transactions shifts depending upon how an EMV card is processed. Specifically, some consumers have heard rumors that swiping an EMV card rather than dipping it leaves them (rather than the merchant or card issuer) liable for any ensuing fraudulent use of the card.

The issue of fraud liability has evolved with the introduction of EMV cards, but that liability has not been passed back onto cardholders. According to CreditCards.com, that evolution solely concerns determining whether the merchant or the card issuer is the party bears liability for fraud in any given case — cardholders themselves remain protected from liability, regardless of whether their EMV cards are swiped or dipped:

Cardholders may be adjusting to "dipping" their chip cards instead of swiping them, but they won't have to adjust to fraud liability changes.

If an authorized transaction occurs against a consumer's credit account, they will continue to be reimbursed by their card issuer for the charges per the major networks' (Visa, MasterCard, American Express and Discover) zero-liability policies. If the issuer finds that the fraud occurred at a non-EMV compliant merchant, it can request a refund for the chargeback transaction, but the consumer is not involved.

Consumers will not be responsible for fraud charges that result from a merchant not being prepared to properly accept EMV cards or because their card issuer has not yet sent them a chip-embedded card.

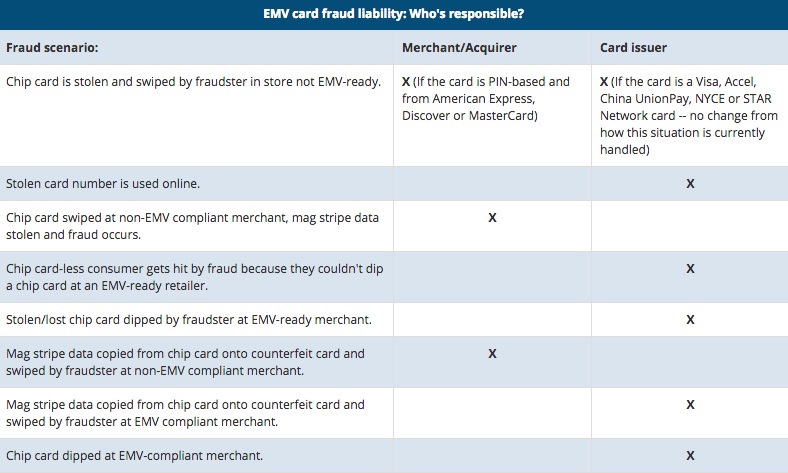

What the new rules govern is whether merchants or card issuers (i.e., banks and credit unions) are liable in cases of credit card fraud, with responsibility now falling upon whichever party was least EMV-compliant:

Today, if an in-store transaction is conducted using a counterfeit, stolen or otherwise compromised card, consumer losses from that transaction fall back on the payment processor or issuing bank, depending on the card's terms and conditions.

Following an Oct. 1, 2015 deadline created by major U.S. credit card issuers MasterCard, Visa, Discover and American Express, the liability for card-present fraud shifted to whichever party is the least EMV-compliant in a fraudulent transaction.

Consider the example of a financial institution that issues a chip card used at a merchant that has not changed its system to accept chip technology. This allows a counterfeit card to be successfully used.

"The cost of the fraud will fall back on the merchant," [chip card service company president Martin] Ferenczi says.

The change is intended to help bring the entire payment industry on board with EMV by encouraging compliance to avoid liability costs.

A separate article on that web site illustrated the liability shifts with a chart:

Many consumers have noticed that although some merchants have seemingly upgraded to EMV-compliant POS terminals, the card slots on those terminals are puzzlingly non-operational (and thus require that customers swipe their chipped cards). As the New York Times noted in March 2016, that situation is the result of merchants' having to wait for certification of their terminals:

Avi Kaner, a co-owner of the Morton Williams supermarket chain in New York, has spent about $700,000 to update the payment terminals at his stores.

Trouble is, he cannot turn them on.

The new terminals can accept credit and debit cards with embedded digital chips, a security feature intended to reduce the number of fraudulent purchases.

But before the payment systems can work, they must be certified, a process that Mr. Kaner and many retailers around the country are waiting to happen. In the case of Morton Williams, the holdup has lasted several months.

The cost of waiting, retailers say, is piling up. Until recently, banks covered much of the cost of fraudulent purchases. Since Oct. 1, though, merchants that cannot accept chip cards have had to shoulder the cost of fraud, and banks have not been shy about passing along the bill.

For years, retailers have argued that the technology, commonly referred to as E.M.V., which stands for Europay, MasterCard and Visa, the technology’s early advocates, mainly protected banks. Mr. Peterson estimated that only 40 to 50 percent of retailers are capable of accepting chip cards.

Kaner told the newspaper he believed consumers were taking advantage of the interim period to file suspicious chargebacks due to the shift in liability:

Mr. Kaner worries that some customers may be using the Oct. 1 liability shift to get out of paying for legitimate purchases. The number of chargebacks, he said, has risen sharply.

“It started out as a trickle, and now it’s turning into a flood,” he said. “In the first couple months, it might have been a few hundred dollars a month. Now, it’s thousands a month.”

Terry Crowley, CEO of processor TranSend, told KrebsonSecurity that consumer dishonesty was a larger issue than consumer liability during the transition period:

Crowley predicts that plenty of smaller merchants could soon get hit with a wave of chargebacks from unscrupulous people abusing the liability shift at merchants that still don’t offer the chip dip.

“There’s an invisible hand at work that is about to kick everyone in the pants and accelerate U.S. dipping into EMV slots,” Crowley said. “If you use a chip card at a point of sale that says swipe — and you later say that wasn’t me — there’s very little a merchant can do to dispute that charge. It’s going to happen because what people aren’t thinking about is the friendly fraud. When people are made aware that if I swipe and I have a chip card, that lunch can be free if I’m a bad consumer.”

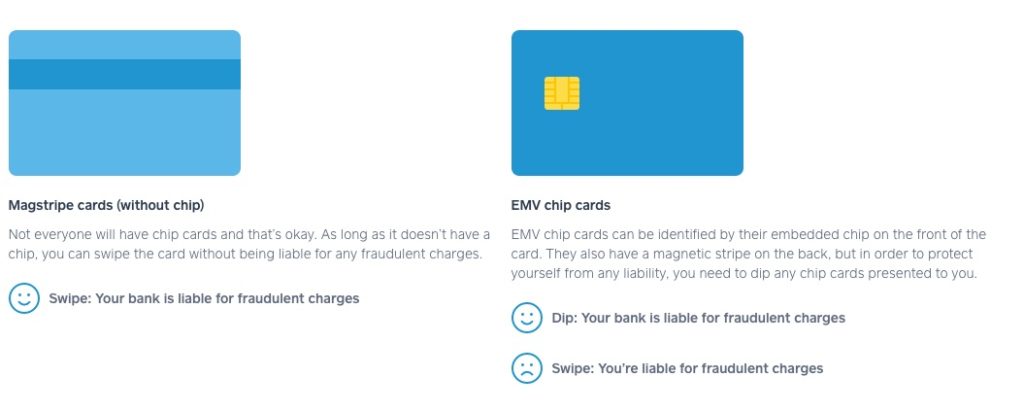

It's possible cardholders have confused information intended for merchants as being directed at them.

Processor Square published a short instructional guide for the EMV card liability shift that might have caused such confusion among consumers who didn't realize the pronoun "you" referred to merchants and not cardholders:

But, in short, consumers don't have to adjust to fraud liability changes with EMV cards. That's an issue for merchants and card issuers to sort out between them.