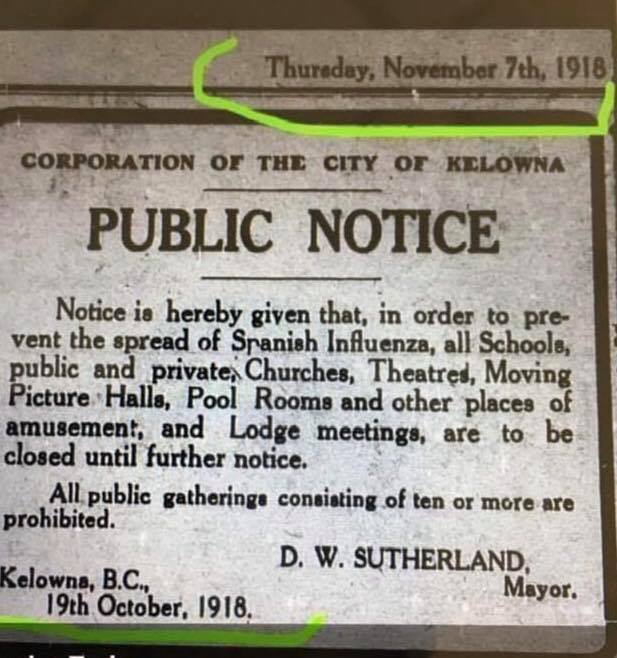

In March 2020, as cities around the world announced "shelter-in-place" or "self-quarantine" orders in an effort to reduce the spread of COVID-19, social media users started to circulate an image that supposedly showed a newspaper clipping from 1918 with a similar announcement in the town of Kelowna, British Columbia:

The clipping reads:

Public Notice.

Notice is hearby given that, in order to prevent the spread of Spanish Influenza, all Schools, public and private, Churches, Theaters, Moving Picture Halls, Pool Rooms and other places of amusement, and Lodge meetings, are to be closed until further notice.

All public gatherings consisting of 10 or more are prohibited.

D. W. Sutherland, Mayor.

Kelowna, B.C., 19 October 1918.

This is a genuine newspaper clipping that was published in the Kelowna Record in 1918 as this Canadian town, as well as the rest of the world, fought to prevent the spread of the H1N1 virus, commonly and misleadingly called the "Spanish Flu." The clipping was archived by the University of British Columbia and can be viewed here.

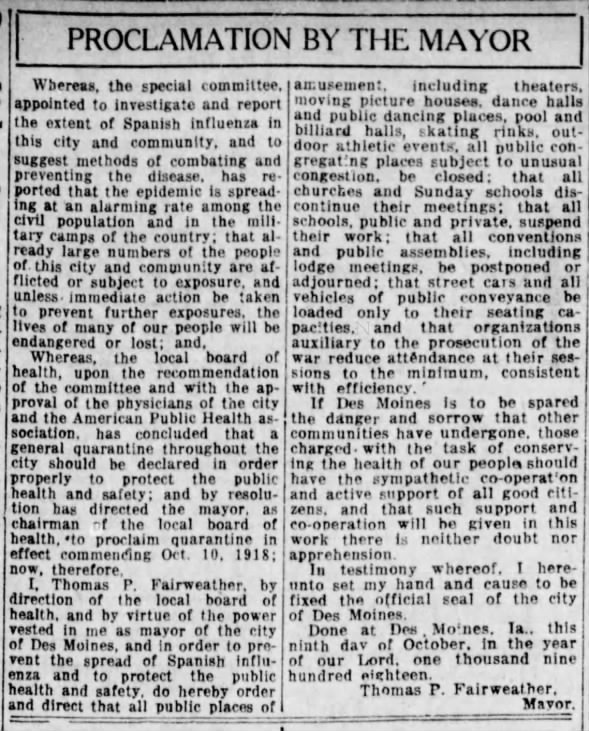

Kelowna, of course, was not the only city to issue such an order. We searched the archives of Newspapers.com and found several similar announcements in cities across the United States.

On Oct. 10, 1918, for instance, Des Moines, Iowa, Mayor Thomas P. Fairweather announced that "in order to prevent the spread of Spanish Influenza and to protect the public health and safety," he was directing "all public places of amusement, including theaters, moving pictures houses, dance halls and public dancing places, pool and billiard halls, skating rinks, outdoor athletic events, all public congregating places subject to unusual congestion, be closed."

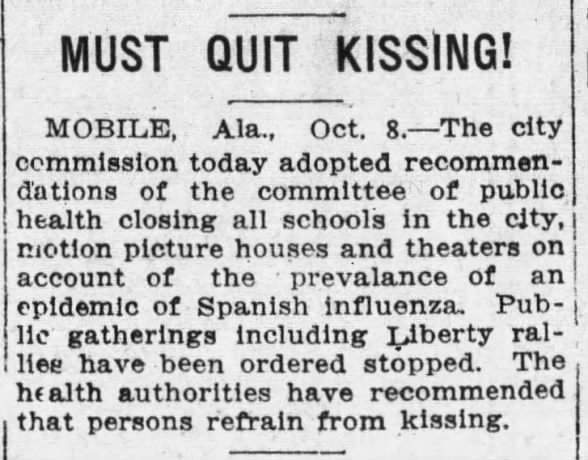

Mobile, Alabama, took these closures one step further. In addition to closing restaurants and businesses, Mobile also asked people to refrain from kissing:

In 1918, just like today, individual cities and states made the decision to close schools, businesses, and public gathering places. According to a recent study from the Journal of the American Society of Cytopathology, cities that implemented strict social guidelines during the early days of the 1918 pandemic saw lower transmission rates and reduced total mortalities.

During the 1918-19 H1N1 "Spanish" influenza pandemic, which infected a fifth to a third of the world population, and during which 50 million people have died worldwide, including an estimated 675,000 Americans, the United States has adopted a range of nonpharmaceutical (public health) interventions. These measures, which were similar to those currently adopted, included closure of schools and churches, banning of mass gatherings, mandated mask wearing, case isolation, and disinfection/hygiene measures. However, these measures were not implemented at the same time or for the same duration in different cities, nor were they uniformly followed. A recent analysis concluded that in some cities (San Francisco, St. Louis, Milwaukee, and Kansas City), where the measures were implemented early, they reduced transmission rates by up to 30–50%. Cities that implemented such measures earlier had greater delays in reaching peak mortality, and had lower peak mortality rates and lower total mortality. The duration that these “social distancing” measures were kept in place correlated with a reduced total mortality burden. Although we still have no known effective therapy or vaccine prevention for this coronavirus, and the world is a quite different place than it was 100 years ago, the efficacy of the measures instituted during the 1918-19 pandemic gives us hope that the current measures will also limit the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

National Geographic saw a similar pattern when it looked at the total deaths during the 1918 pandemic in various cities in the U.S. Philadelphia, for instance, held a large parade a few days after its first H1N1 death and saw a major spike in deaths. St. Louis, on the other hand, implemented social-distancing measures early on and managed to delay its mortality peak:

PHILADELPHIA DETECTED ITS first case of a deadly, fast-spreading strain of influenza on September 17, 1918. The next day, in an attempt to halt the virus’ spread, city officials launched a campaign against coughing, spitting, and sneezing in public. Yet 10 days later — despite the prospect of an epidemic at its doorstep — the city hosted a parade that 200,000 people attended ...

... Shortly after health measures were put in place in Philadelphia, a case popped up in St. Louis. Two days later, the city shut down most public gatherings and quarantined victims in their homes. The cases slowed. By the end of the pandemic, between 50 and 100 million people were dead worldwide, including more than 500,000 Americans — but the death rate in St. Louis was less than half of the rate in Philadelphia. The deaths due to the virus were estimated to be about 385 people per 100,000 in St Louis, compared to 807 per 100,000 in Philadelphia during the first six months — the deadliest period — of the pandemic.

In short, the 1918 newspaper clipping from Kelowna, British Columbia, that announced the closures of schools, businesses, and other public places during the H1N1 pandemic is real, but not unique. Similar announcements were made in a variety of cities in an attempt to slow the spread of the Spanish flu.