In June 2019, a wide variety of news publications reported that researchers had identified a rather startling development in human physiology due to the use of technology: horns or "spikes" were growing out of the base of young people's skulls as a result of their constantly looking down at cellphone screens. The problem with those headlines was that the underlying claim was unfounded.

For example, the Washington Post reported that researchers at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Queensland, Australia, had found a "hook or hornlike feature jutting out from the skull, just above the neck" that represented "the first documentation of a physiological or skeletal adaptation to the penetration of advanced technology into everyday life."

That study, published on 20 February 2018 in the journal Scientific Reports, focused on a feature known to scientists as the external occipital protuberance (EOP), a bump on the back of the skull in the middle, just where the neck muscles attach to the head. The anomaly characterized by the paper's authors was described as an enlarged EOP (or EEOP).

"We hypothesize EEOP may be linked to sustained aberrant postures associated with the emergence and extensive use of hand-held contemporary technologies, such as smartphones and tablets," the authors stated. "Our findings raise a concern about the future musculoskeletal health of the young adult population and reinforce the need for prevention intervention through posture improvement education."

After the story went viral, various publications poked holes in the research, with tech news site Gizmodo pointing out that the use of the term "hypothesis" indicated that nothing has been proved about the paper's findings.

Meanwhile, the New York Times reported that although users' spending a lot of time hunched over devices was known to cause pain, the study lacked a control group and thus couldn't show cause and effect. Moreover, the research also focused on a group that was already experiencing enough pain to undergo diagnostic x-rays for it. Thus, "it's not clear what bearing the results have on the rest of the population."

Although it's possible that a bone spur could form from constantly straining the neck forward, it represented a big "so what?" to Dr. Evan Johnson, an assistant professor and director of physical therapy at New York-Presbyterian Och Spine Hospital who was quoted by the Times. The more worrisome finding would be if cellphone use were responsible for widespread changes in posture that could result in long-term musculoskeletal problems.

Paleoanthropologist John Hawks didn't buy it at all. "Horns growing on young people’s skulls? It’s a juicy headline, but it’s not the truth," he said. The idea may play into a moral panic about the effects of cellphone use on humans, but the research doesn't back it up, he wrote in a 24 June 2019 blog post.

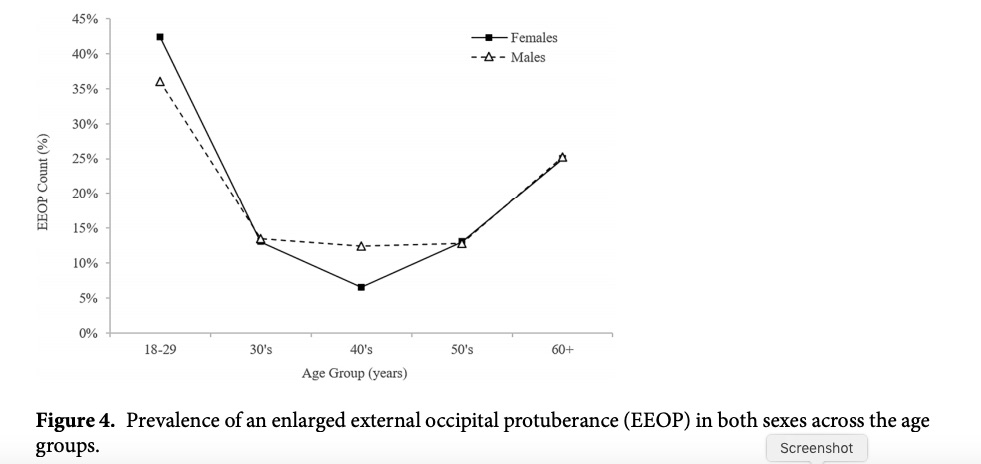

Hawks said he believes major errors undermine the paper's credibility, the most obvious one being the inclusion of a graph that didn't match the paper's text. The study's authors noted that males were 5.48 times more likely than females to have an enlarged EOP and included a graph that appeared to show younger people between the ages of 18 and 29 years having a much higher prevalence of enlarged EOP than people between the ages of 30 and 50 years. But the graph didn't match the finding that men were more than five times as likely as women to have an enlarged EOP -- it instead "shows both sexes having very high and similar frequencies," Hawks said:

Hawks also questioned whether many of the x-ray images were really enlarged EOPs or illusions created by the angle at which the x-rays were taken. "They are more likely side views of the thickened area of the superior nuchal line," he noted. "Altogether, this means that what the authors are looking at might have nothing to do with what an anthropologist can see on a bone at all. It might be an illusion."

The Times also quoted Dr. David J. Langer, chairman of neurosurgery at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York. Common ailments among surgeons, whose professions require them to spend a lot of time looking down, include degenerative disc disease and neck misalignment, not protruding horn growths. "Head horns?" Langer asked. "Come on.”