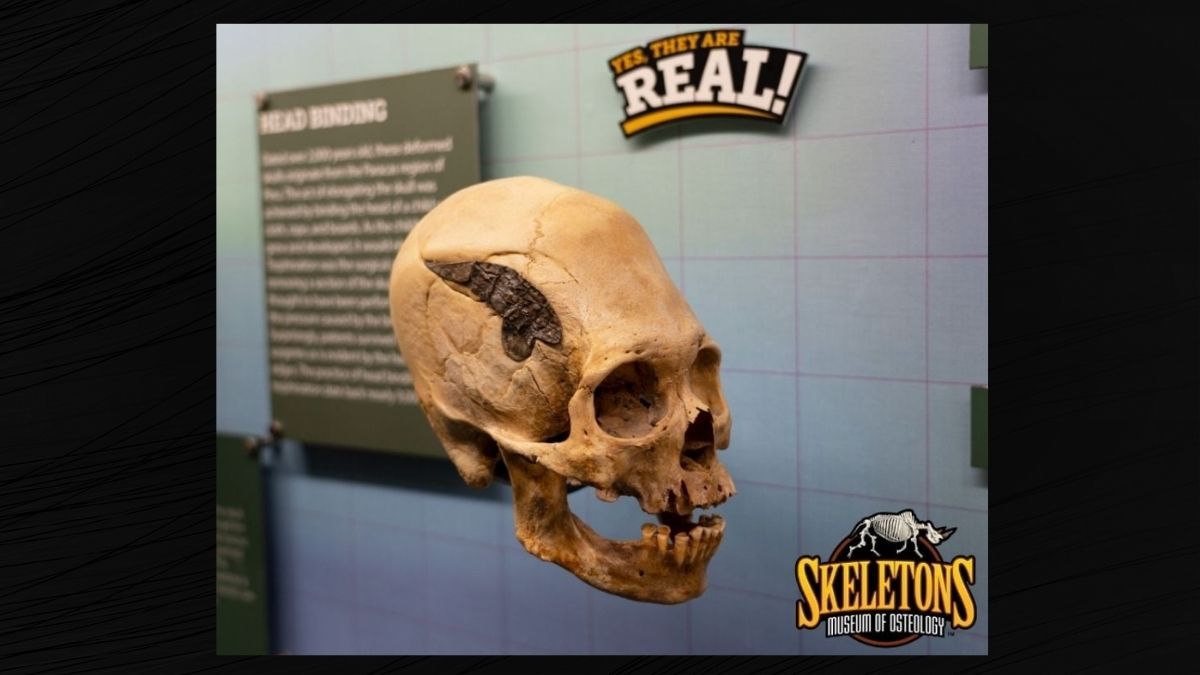

In 2020 and 2021, the Museum of Osteology in Oklahoma posted photographs of a 2,000-year-old skull with a feature that might be surprising to modern audiences. The skull had evidence of a surgical procedure intended to mend a skull fracture:

The text included in the above post, dated April 22, 2021, reads:

Last year we posted this elongated skull with metal surgically implanted to help heal a traumatic injury. This skull is now on public display at our museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. We thought we would answer some of your commonly asked questions below.

Yes, this is a real human skull that is thousands of years old. Elongation was achieved through head binding beginning at a very young age. It was typically practiced to convey social status by various cultures.

This individual survived the [metal] procedure, known as trephination, based on evidence of bone remodeling. Trephination was practiced by nearly all ancient civilizations by different means and for different reasons.

The material used was not poured as molten metal. We do not know the composition of the alloy. The plate was used to help bind the broken bones. Although we can't guarantee anesthesia was used, we do know many natural remedies existed for surgical procedures during this time period.

In the April 2020 post mentioned above, the skull was estimated to be 2,000 years old and belonged to a soldier injured in battle. Surprising as it may seem, the patient survived the procedure, as evidenced by the fact that bone surrounding it fused together.

National Geographic reported that the procedure, known as trepanation, was relatively common in what was then the Inca Empire in South America, because in that region, the weapons of war were primarily sling stones and clubs — weapons that had a high likelihood of causing serious head injuries.

John Verano, a physical anthropologist at Tulane University and author of the book "Holes in the Head: The Art and Archaeology of Trepanation in Ancient Peru," told National Geographic that the survival rate was surprisingly high, around 70 percent.

The museum also noted that the skull was elongated, a procedure that was done in that region for what researchers believe were religious and aesthetic reasons.