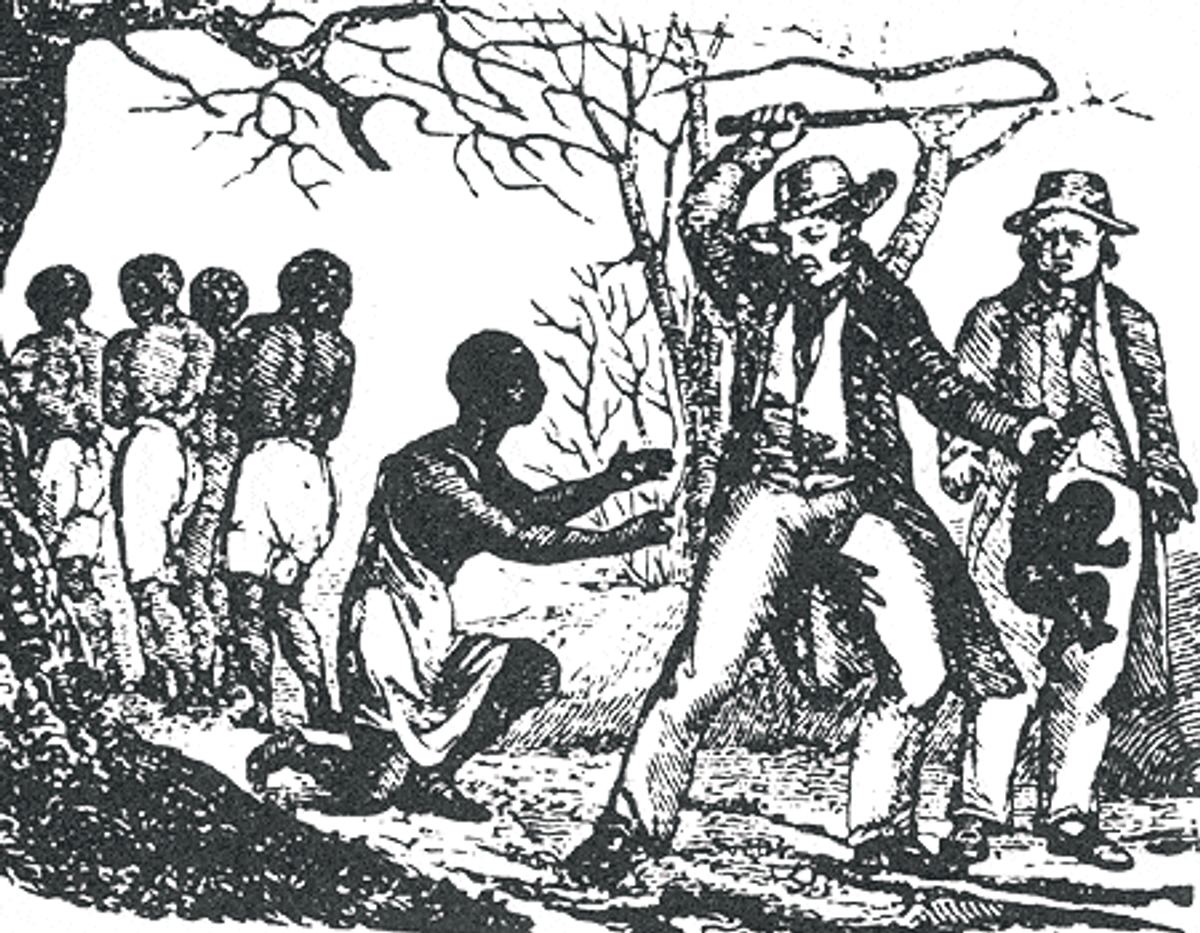

Misinformation about the antebellum South, the Civil War, and the practice of slavery in the U.S. is rife on the Internet. Perhaps nowhere more so than in a widespread and ironically titled "Truth about Confederate History" article.

Slavery in the United States

In the wake of the June 2015 racially motivated shooting that left nine people dead at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, and the renewed debate that event prompted about the propriety of displaying Confederate flags on the grounds of the South Carolina state capital (and elsewhere), a long-circulating article advertised as dispelling "falsehoods and inaccuracies of Confederate and Southern history" attracted renewed interest.

Addressing and correcting the many inaccuracies and misleading statements contained in that piece would require a very lengthy article, so we have chosen to tackle it here in smaller, more easily digestible chunks. Our first installment dealt with the history of the Confederate flag; in this second installment, we examine "facts" asserted in a section of "the Truth about Confederate History" about the practice of slavery in the U.S. and its eventual abolition.

Specifically, we'll be assessing the statements from "the Truth about Confederate History" reproduced in the shaded box below, which claim to be separating myth from fact (while doing anything but):

MYTH: Only Southerners owned slaves.

FACT: Entirely untrue. Many Northern civilians owned slaves. Prior to, during and even after the War of Northern Aggression.

Surprisingly, to many history impaired individuals, most Union Generals and staff had slaves to serve them! William T. Sherman had many slaves that served him until well after the war was over and did not free them until late in 1865.

U.S. Grant also had several slaves, who were only freed after the 13th amendment in December of 1865. When asked why he didn't free his slaves earlier, Grant stated "Good help is so hard to come by these days."

Contrarily, Confederate General Robert E. Lee freed his slaves (which he never purchased — they were inherited) in 1862! Lee freed his slaves several years before the war was over, and considerably earlier than his Northern counterparts. And during the fierce early days of the war when the South was obliterating the Yankee armies!

Lastly, and most importantly, why did NORTHERN States outlaw slavery only AFTER the war was over? The so-called "Emancipation Proclamation" of Lincoln only gave freedom to slaves in the SOUTH! NOT in the North! This pecksniffery even went so far as to find the state of Delaware rejecting the 13th Amendment in December of 1865 and did not ratify it (13th Amendment / free the slaves) until 1901!

Who Owned Slaves?

"Many Northern civilians owned slaves. Prior to, during and even after the War of Northern Aggression."

"Mommy, he did it too!" is rarely a cogent or convincing form of historical argument, especially when — as in this case — one is referring to actions that were very different in degree and time.

It is true that slavery was not unique to the South: Both during the colonial era and after independence, slavery existed in areas that now comprise what we consider "Northern" states. But the suggestion that "many Northern civilians" owned slaves at the time of the Civil War is flat out wrong. All of the Northern states, with a single arguable exception, had (by law or by practice) ended slavery within their borders long before the Civil War began.

Where did legalized slavery still exist in the North in 1861? Only in Delaware, a state which was far from being undeniably a "Northern" state: depending upon the criteria used, one could justifiably have pegged Delaware at the time of the Civil War as being Northern, Southern, Mid-Atlantic, or some combination thereof. Either way, even though legislative efforts to abolish slavery in Delaware had been unsuccessful, by the time of the 1860 census 91.7% of Delaware's black population was free, and fewer than 1,800 slaves remained in the state — hardly a condition supportive of the notion that "many" Northerners owned slaves.

Although Missouri, Kentucky, and Maryland never formally seceded from the Union, they were not "Northern" states in either a geographic or a cultural sense. All were home to substantial pro-Confederate elements and contributed significant numbers of troops to the Confederate side during the Civil War. Kentucky and Missouri were both claimed as member states by the Confederacy and were represented in the Confederate Congress, and Maryland remained in the Union primarily because U.S. troops quickly imposed martial law and garrisoned the state to head off secession efforts. (Maryland had to be kept in the Union by any means necessary, else the United States capital in the District of Columbia would have been completely enclosed within Confederate territory.) The state of New Jersey was something of an outlier. Although the New Jersey legislature passed a gradual emancipation measure in 1804 and permanently abolished slavery in 1846, the state allowed some former slaves to be reclassified as "apprentices for life" — a condition that could be considered slavery in all but name. Nonetheless, the 1860 census recorded only 18 slaves in all of New Jersey.

Did Civil War Generals Own Slaves?

"William T. Sherman had many slaves that served him until well after the war was over and did not free them until late in 1865."

Although renowned Union general William T. Sherman was rather conservative on the issue of slavery (he was far from an abolitionist) and did not believe in equal rights for "negroes," there is scant evidence that he ever owned any slaves — he certainly did not own "many," nor did he own any during the course of the Civil War.

Throughout most of his pre-war life Sherman had little opportunity to own slaves, as he lacked the money to purchase them and/or lived in states (California, Indiana, and Ohio) where slavery was not legal. About the only periods in his life when he could conceivably have owned slaves would have been between 1840-46, when he was a U.S. Army officer stationed in Southern states (Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina), and 1859, when he was the superintendent of Louisiana State Seminary of Learning and Military Academy (now Louisiana State University). We found only one biography (out of many) that supported the notion that Sherman ever owned slaves, and that work merely stated, without elaboration, that Sherman "had a slave" at some point during the former period (a wording that allows for the possibility that Sherman rented or was tended to by a slave for a while rather than actually owning one).

'U.S. Grant also had several slaves, who were only freed after the 13th amendment in December of 1865. When asked why he didn't free his slaves earlier, Grant stated "Good help is so hard to come by these days."'

The only evidence that Union general (and later United States President) Ulysses S. Grant ever owned any slaves is a document he signed in 1859 that emancipated "my Negro man William" (i.e, William Jones), whom Grant stated in the document he had purchased from Frederick Dent (his father-in-law). Little is known about William Jones; as even Grant's biographers note, "exactly when and how Grant acquired ownership of a slave remain something of a mystery." There is no other evidence showing that Grant ever owned more than this one slave, much less "several."

It is often stated that Grant's wife, Julia Boggs Dent, "owned four slaves," and Julia herself identified four "servants" whom she claimed "belonged" to her up until the end of 1862. However, those slaves had been purchased by Julia's father, Frederick F. Dent, and there is no record of his ever having transferred ownership of them to Julia — without such a transfer, neither Julia nor her husband Ulysses would have had legal authority to free them.

From 1854 to 1859 Grant managed his father-in-law's farm, White Haven, where a number of slaves lived and worked. But again, those slaves belonged to Grant's father-in-law, so Grant himself had no legal authority to set them free. (Some of the slaves at White Haven eventually drifted off during the Civil War; any that remained were freed when Missouri's constitutional convention abolished slavery in January 1865.)

The statement attributed to Grant about not his freeing his slaves earlier than December 1865 (when the 13th Amendment was adopted) because "Good help is so hard to come by these days" is almost certainly an apocryphal one. No credible documentation records Grant as having said such a thing, and he was only ever in a position to emancipate a single slave, which he did back in 1859.

"Contrarily, Confederate General Robert E. Lee freed his slaves (which he never purchased — they were inherited) in 1862! Lee freed his slaves several years before the war was over, and considerably earlier than his Northern counterparts."

Robert E. Lee, the commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and (from 1865) the general-in-chief of Confederate forces, neither owned slaves nor inherited any, thus it is not correct to assert that he "freed his slaves" (in 1862 or at any other time).

As in the case of Ulysses S. Grant, the slaves that Lee supposedly owned actually belonged to his father-in-law, George Washington Parke Custis, and lived and worked on the three estates owned by Custis (Arlington, White House, and Romancoke). Upon Custis' death in 1857, Lee did not "inherit" those slaves; rather, he carried out the directions expressed in Custis' will regarding those slaves (and other property) according to his position as executor of Custis' estate.

Custis' will stipulated that all of his slaves were to be freed within five years: "... upon the legacies to my four granddaughters being paid, then I give freedom to my slaves, the said slaves to be emancipated by my executor in such manner as he deems expedient and proper, the said emancipation to be accomplished in not exceeding five years from the time of my decease." So while Lee did technically free those slaves at the end of 1862, it was not his choice to do so; he was required to emancipate them by the conditions of his father-in-law's will.

When Was Slavery Outlawed?

"Lastly, and most importantly, why did NORTHERN States outlaw slavery only AFTER the war was over?"

This statement is somewhat ambiguous. If it refers to individual states, then it is false: all the Northern states (again, with the arguable exception of Delaware) had abolished slavery well before the start of the Civil War. If it refers to the federal government, then it's still false: the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude in the United States, was initially passed by the U.S. Senate on 8 April 1864, more than a year before the end of the Civil War (although it was not ratified by the requisite number of states until December 1865).

The answer to the question of why the Northern states didn't outlaw slavery prior to the Civil War is an obvious one: it simply wasn't possible. As long as the Southern slave states remained in the Union, their aggregate Congressional representation was sufficient in number to block the passage or ratification of any law or constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. The 13th Amendment could not have passed until the Southern states, having seceded from the Union, were no longer represented in the U.S. Congress. (Some of the former Confederate states did eventually ratify the 13th Amendment after its passage by Congress, because they were required to do so as a post-war condition of regaining federal representation.)

What Was the Emancipation Proclamation?

'The so-called "Emancipation Proclamation" of Lincoln only gave freedom to slaves in the SOUTH! NOT in the North!'

Despite its status as one of the most important documents in the history of the United States, the Emancipation Proclamation is still misunderstood by many Americans. It was neither a law passed by Congress nor the equivalent of a constitutional amendment, with the power to free slaves everywhere throughout the United States (and former states then in the Confederacy); it was an executive order issued as a wartime measure by President Lincoln, based on his constitutional authority as commander in chief of the armed forces. Accordingly, Lincoln had no legal authority to free all slaves everywhere, only in the "states and parts of states in which the people thereof" were in "rebellion against the United States."

Since none of the Northern states had rebelled against the United States, the Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to them. It also did not apply to slave states that had not seceded from the Union (Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware, and Missouri), to the Virginia counties that had opted to break away from that state (and were soon to be admitted to the Union as the state of West Virginia), nor to the parts of the Confederacy that were deemed to be no longer in a state of rebellion against the United States (Tennessee and lower Louisiana) because they were occupied by Union troops.

"This pecksniffery even went so far as to find the state of Delaware rejecting the 13th Amendment in December of 1865 and did not ratify it (13th Amendment / free the slaves) until 1901!"

This is the single item this section of "Truth about Confederate History" actually got right: Delaware was one of three states (along with Kentucky and Mississippi) that initially rejected the 13th Amendment outlawing slavery and did not ratify it until after the start of the 20th century, by which time the amendment had long since become part of the Constitution. Slavery in Delaware nonetheless ended with the adoption of that amendment in December 1865.