The printed bank deposit slip is becoming scarce as more and more people receive payments through direct deposits and use automated teller machines which do not require such paperwork. But before all these means of electronic bookkeeping were established, a typical Friday ritual for most working folk was to trudge to the local bank with one's paycheck, fill out a deposit slip, and stand in line to deposit the check.

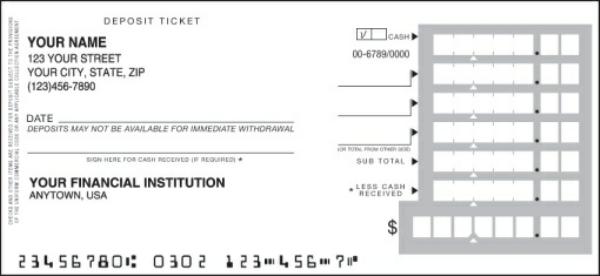

Some people used the deposit slips that were furnished with their checkbooks and had their account numbers already printed on them, but those who didn't carry deposit slips with them (such as customers who had only savings accounts) typically used the blank slips provided by their banks in every branch office.

Banks preferred that their customers use pre-printed slips, because those slips included the customers' account numbers printed in the machine-readable magnetic ink used by their data processing systems and could be sorted automatically, but slips lacking printed account numbers were singled out by the machines for manual sorting. (As well, when customers had to fill in their own account numbers on deposit slips, they sometimes got them wrong, wrote them illegibly, or forgot to include them at all.)

If a deposit slip should somehow include both a printed account number and a handwritten one, the sorting machines would process it based solely on the printed number, which supposedly gave rise to an ingenious scam:

[A] new customer picked up a hefty batch of [blank] deposit slips, but he did not fill them out. Instead, he took them to premises where a typewriter equipped to write in magnetic-ink characters was available. Using this special typewriter, he imprinted his account number in magnetic ink at the bottom of the blank deposit forms. He then returned to the bank on different occasions and added these magnetically-printed forms to the neat pile of blank deposit slips in the trays. Then he went away and waited for the jackpot

Other customers streamed into the bank and, dipping into the trays of deposit slips, innocently recorded their own deposits in the usual way ... the computer funneled the deposits of scores of the bank's customers into the new depositor's account. And by the time the customers began to complain that checks they were issuing against their deposits were bouncing, the new depositor, to whose account other depositors had miraculously added a quarter of a million dollars, had drawn out a hundred thousand of it and disappeared.

Con man Frank W. Abagnale (of Catch Me If You Can fame) claimed in his memoirs that he successfully pulled off this scam:

There was a fellow beside me filling out a deposit slip. I noticed he neglected to give his account number. I dawdled in the bank for nearly an hour and watched those who came in to deposit cash, checks or credit-card vouchers. Not one in twenty, if that many, used the space provided for his or her account number.

I surreptitiously pocketed a sheaf of the deposit slips, returned to my apartment and, using press-on numerals matching the type face on the bank forms, filled in the blank on each slip with my own account number.

The following morning, I returned to the bank and just as stealthily put the sheaf of deposit slips back in a slot atop a stack of others. I didn't know if my plot would succeed or not, but it was worth a risk. Four days later I returned to the bank and made a $250 deposit. "By the way, what's my balance, please?" I asked the teller. "I forgot to enter some checks I wrote this week."

The teller obligingly called bookkeeping. "Your balance, including this deposit, it $42,876.45, Mr. Williams," she said.

Just before the bank closed, I returned and drew out $40,000 in a cashier's check, explaining I was buying a home. I didn't buy a home, of course, but I sure did feather my nest.

However, many of the alleged cons that Abagnale allegedly pulled off, as chronicled in Catch Me If You Can, proved unverifiable, and Abagnale ackowledged that the book's co-author "over dramatized and exaggerated some of the story." The book appears to contain recitations of a number of putative scams that Abagnale or his co-author merely heard about anecdotally and falsely incorporated in the book as real-life incidents.

If it was ever perpetrated in the real world, this scheme is unlikely to have worked for very long. Bank customers would soon have started inquiring about their missing deposits, and the errant checks would quickly have been traced to the scammer's account. Once that happened, the scammer's account would have been flagged so that any further transactions would trigger additional scrutiny, thereby exposing the scam in short order.