For more than a century, scholars and experts have puzzled over the mysterious manuscript known today as the “Voynich Manuscript,” which has appeared and vanished through history. Rediscovered in 1912 by rare books dealer Wilfrid Voynich, after whom it is named, it now resides in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University.

Made up of mysterious drawings and indecipherable texts, the manuscript was written in central Europe sometime during the 15th century and once belonged to the library of the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II. Rudolph acquired it from English astrologer John Dee, apparently, but believed it was the work of Roger Bacon. Dee’s son noted that his father owned “a booke…containing nothing butt Hieroglyphicks, which booke his father bestowed much time upon: but I could not heare that hee could make it out.” At one point it emerged in 1903 at a secret book sale by the Society of Jesus in Rome. It passed through various hands, until Voynich purchased the manuscript from the Jesuit College near Rome, and in 1969 it was given to the Yale Library by H. P. Kraus, who purchased it from Voynich’s widow.

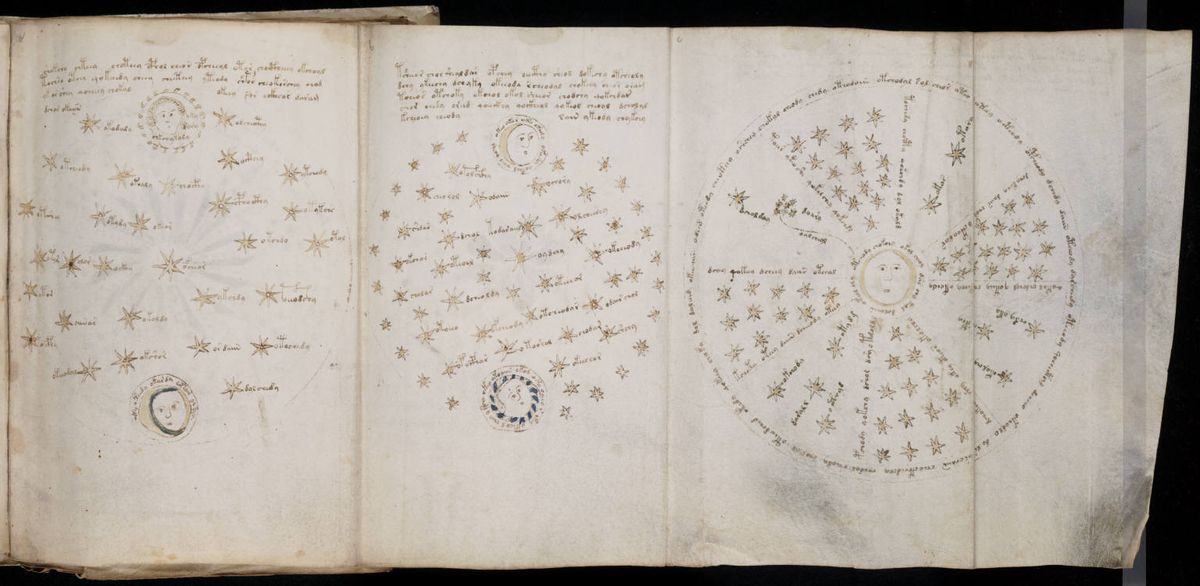

According to Beinecke Library, the book is described as a “magical or scientific text” and “nearly every page contains botanical, figurative, and scientific drawings of a provincial but lively character, drawn in ink with vibrant washes in various shades of green, brown, yellow, blue, and red.”

The library also summarizes what the book contains, based on the subject matter depicted in the drawings:

1) botanicals containing drawings of 113 unidentified plant species;

2) astronomical and astrological drawings including astral charts with radiating circles, suns and moons, Zodiac symbols such as fish (Pisces), a bull (Taurus), and an archer (Sagittarius), nude females emerging from pipes or chimneys, and courtly figures;

3) a biological section containing a myriad of drawings of miniature female nudes, most with swelled abdomens, immersed or wading in fluids and oddly interacting with interconnecting tubes and capsules; 4) an elaborate array of nine cosmological medallions, many drawn across several folded folios and depicting possible geographical forms;

5) pharmaceutical drawings of over 100 different species of medicinal herbs and roots portrayed with jars or vessels in red, blue, or green, and

6) continuous pages of text, possibly recipes, with star-like flowers marking each entry in the margins.

But what does the language of the book actually mean? Many have attempted to decipher it and in 2017, a history researcher Nicholas Gibbs claimed in the Times Literary Supplement to have uncovered its meaning. He argued it was a medieval health manual copied from other sources, and its indecipherable cipher consisted of abbreviated medical recipes.

Other researchers swiftly shut his claims down, pointing out that his so-called original findings had already been discovered by other experts, and that they didn’t buy the argument about abbreviations. Harvard’s Houghton Library curator John Overholt tweeted:

René Zandbergen, a researcher of the manuscript, who runs the popular site Voynich.nu, made a similar argument about the medical nature of the text on his website:

The following section of the Voynich MS has traditionally been called the biological section, though others prefer to call it the balneological section. D'Imperio qualifies it as the most unusual part of the Voynich MS.

It contains drawings of so-called nymphs, similar to the ones mentioned above in the zodiac section, populating arrangements of pipes or vessels, and what seem like baths or clouds. Many illustrations leave the impression of representing a chemical (alchemical) or natural process. They have also been compared to organs in the human body.

Several people have, independently from each other, pointed out a resemblance of these illustrations with the MSs of the Balneis Puteolanis, a description of some medicinal baths written in the 13th Century.

Zanbergen, in an email to The Atlantic said, “[Gibbs’] summary in the TLS is really too short to provide any serious analysis.”

Lisa Fagin Davis, executive director of the Medieval Academy of America, who also was a doctoral student at Yale, told The Atlantic, “If they had simply sent it to the Beinecke Library, they would have rebutted it in a heartbeat.”

Davis added that Gibbs’ claim rested on the existence of a lost index for the manuscript, which contained illnesses and the plant recipes they corresponded to. For Davis, even though there are missing pages in the manuscript, there is no evidence that those pages were an index.

In 2016, a pair of decoders in Canada also claimed to have deciphered some part of the manuscript. They used a computer program they created to decode the text. They believed that the words were vowelless alphagrams –or anagrams written alphabetically. They trained the algorithm to decipher 380 different language versions of the “United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” Once the algorithm had a high success rate in matching the anagrams to modern words, they fed in some of the text and found 80 percent of the words could be Hebrew. But a Hebrew translator could not convert the text into coherent English, so they turned to Google Translate, as no other scholars were available. After correcting spelling errors they came up with one sentence: "She made recommendations to the priest, man of the house and me and people." They also translated some words in the “herbal” section, coming up with “farmer,” ‘light,” “air,” and “fire.”

There were numerous problems with this study, including the reliance on Google Translate, and how they created an algorithm to identify modern languages, and not medieval ones.

Theories abound about what the manuscript actually means, some saying it is gibberish sold by occult philosophers, others saying it is a pidgin prayer book from a heretical Christian sect. Even if it is a “fake,” it is an “elaborate one,” wrote Reed Johnson, a Russian language lecturer, in the New Yorker:

A twentieth-century scam artist would have to have located a hundred and twenty sheets of blank six-hundred-year-old vellum in anticipation of the invention of radiocarbon dating (which did not yet exist when the manuscript first reëmerged, in 1912). Scholars remain deeply divided over the question of whether the text is likely to be meaningful. But the distribution of letters and words is anything but random, even demonstrating statistical features generally associated with natural-language texts—features that weren’t discovered until the nineteen-thirties.

Ultimately, Johnson wrote, its “resistance to being read is what sets it apart.”