With a striking horn, stout body, lengthy tail and two enormous legs, the so-called Magdeburg Unicorn has been a legend on the internet for years and has haunted the scientific community for centuries.

Every few years, the fabled unicorn makes a reappearance online when people on social media use it as an opportunity to poke fun at the hilarious evolution of science, with some going so far as to dub it "one of the worst fossil reconstructions in human history."

This happened again in August 2022 when a photograph of the unicorn was shared on Twitter and Reddit, collectively receiving more than 200,000 likes.

The "unicorn" was, in part, a woolly rhinoceros, a now-extinct species that once roamed over much of northern Eurasia, until the end of the last Ice Age. The woolly rhino was described for the first time in 1769 — over a century after the "unicorn bones" were unearthed — by naturalist Peter Simon Pallas.

Before we jump into that, we must fully understand the complicated history of the Magdeburg Unicorn and exactly where its fabled saga began.

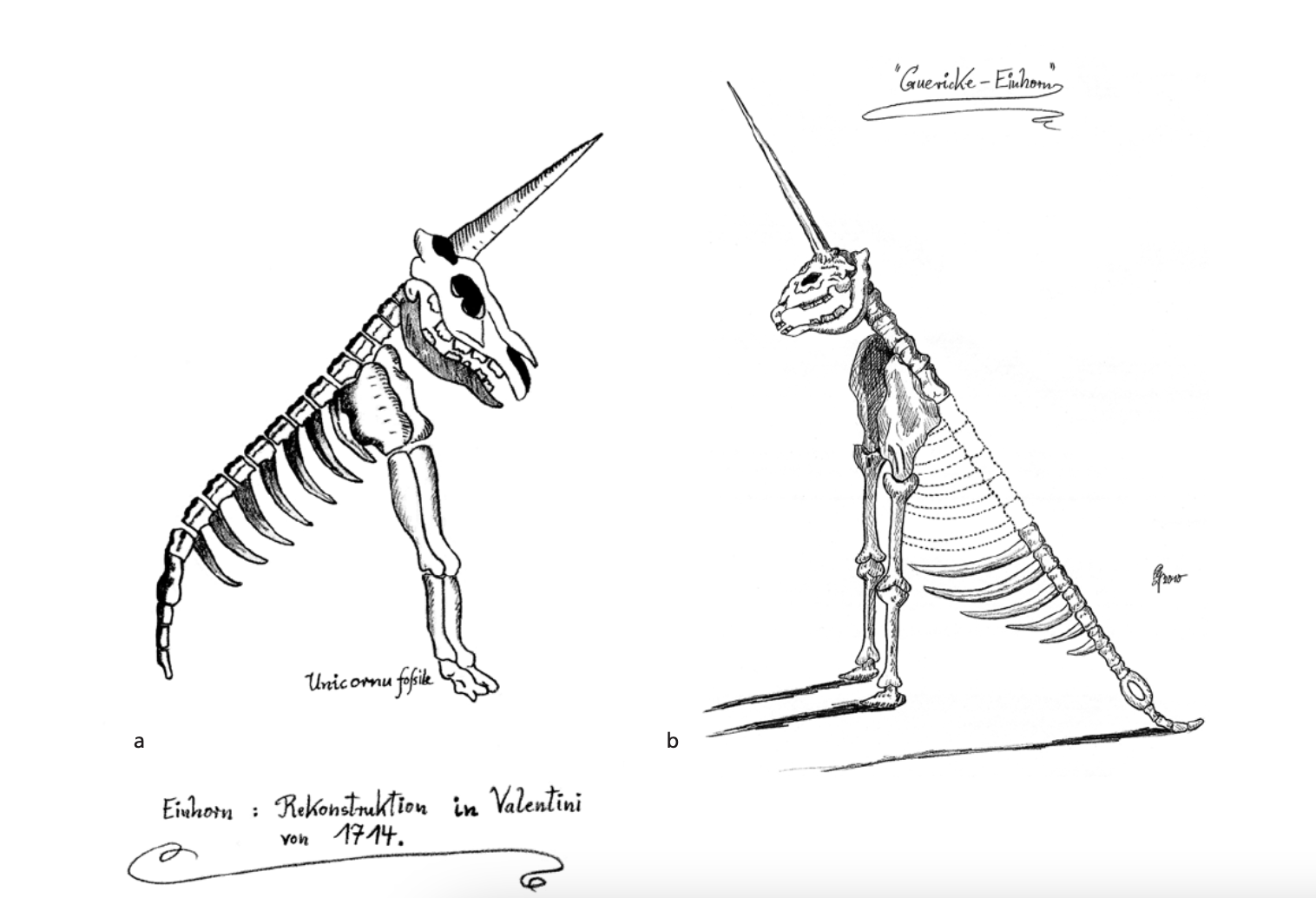

Drawings of the Guericke-Einhorn after Valentini in 1714 (a) and after Leibniz in 1749 (b). Gröning and Brauckmann/The Beef Behind All Possible Pasts

An Enigmatic Discovery

The Magdeburg Unicorn — also known as the Magdeburger Einhorn or Guericke-Einhorn — was a collection of fossils unearthed in 1663 at Seweckenberge, a German steppe known to contain fossils from the ice age and beyond. What is now called the Unicorn Cave is located near the the mountain town of Quedlinburg.

Prussian scientist Otto von Geuricke, who was best known for his invention of the vacuum pump, believed that the collection of fossilized bones belonged to a unicorn. Around five years after their discovery, von Geuricke was said to have reconstructed the bones into the form in which they are most often represented today.

But von Guericke's original 3D reconstruction, if there ever was one, was ultimately lost. That's where philosopher and scientist Gottfried Leibniz comes into the story.

Composite of Guericke (left) and Leibniz (right). Public Domain

What Came First: The Drawings or the Model?

Like von Guericke, Leibniz was a scientist of his time who held both legitimate and fantastical theories. Some of his work was called into question in the 20th-century scientific literature and he has been described as a "sober, cautious, interpreter, a skeptic one might say, but one who is prepared to concede the possibility of many strange phenomena."

But Leibniz also believed there was a place "among the natural curiosities" of the world for "fringe phenomena" and "various monsters" such as talking dogs, genies, prophets and, naturally, the unicorn. He also had a reputation for not always being forthcoming with his views and was known to change his perception based on his audience. After all, science 400 years ago was a different era of understanding and tended to lean more on the philosophical side. What we would call mathematical sciences today, Leibniz referred to as the "philosophy of imaginable things."

The Quedlinburg monster was described in chapter 35 of Leibniz' book "Protogaea," which was a posthumously published treatise on earth sciences that debuted in 1749. The book was the philosopher's attempt to develop "the seeds of a new science called natural geography"— unicorns included.

Found within the chapter, "Concerning the horn of the unicorn and the monstrous animal dug up at Quedlinbury," is a brief mention of the Magdeburg Unicorn:

Since it has been demonstrated by Bartholin that unicorns (once one of the most curious and rarest ornaments of natural history cabinets but now surrendered to the people's admiration) come from fish from the Northern ocean, we are allowed to think that the unicorn fossil found in our countryside has the same origin.

[…]

This skeleton was broken and extracted by pieces, because of the ignorance and the carelessness of the diggers. But the horn, united with the head and some ribs, as well as the backbone and some bones, were brought to the abbess of the place"

The drawing published in "Protogaea" had originally been printed in 1704 by Michael Bernhard [Valentini], who drew it from notes and sketches by von Guericke and descriptions by Johann Mayer. One such image was reproduced by Leibniz and published in his 1749 book.

3D model of the Guericke-Einhorn on display at the Museum für Naturkunde (Natural History Museum) in Magdeburg, Germany. Michael Buchwitz/The Beef Behind All Possible Pasts

Just as the bones confounded 17th-century naturalists, the origination of the reconstruction, both in a 3D version and in print, continues to perplex scientists today. What came first, the drawings or the model? That is a contentious question of whodunnit that is still debated in the scientific literature of today, with some arguing that it was neither von Guericke nor Leibniz:

The author of the first report with a figure was Johannes Meyer, astronomer and treasurer of the Abbes Superior of Quedlinburg; and his German text had been translated by both partly in different ways (Guericke's Experimenta nova, printed in 1672 and used by Leibniz; Leibniz's Protogaea, first printed posthumously in 1749). Discovery, excavation, salvage and reconstruction of the unicorn were ascribed to Guericke only by Othenio Abel (for the first time in 1918 and thereafter on many occasions) without indicating any source for that. His story of the supposed discovery since then has been embellished with a lot of imagination further and further. However, Leibniz himself wrote in his Protogaea, that a figure of the unicorn skeleton (which Guericke does not reproduce) had been sent to him together with a report (by J. Meyer from Quedlinburg); and this figure he and his engraver Nicholas Seeländer 'corrected' and completed in accordance with their own imagination of a unicorn's build in 1716 to illustrate the Protogaea (M. B. Valentini printed a copy of Meyer's original in 1704).

A Puzzling Chimera

Scientists do have a better idea of what exactly the unicorn was made up of. Though many news publications have reported that it was the misaligned remains of a woolly rhinoceros, these claims are only half-true — and may never be conclusively confirmed.

Today, the unicorn is housed at the Museum für Naturkunde in Magdeburg, German. One theory is that the unicorn was likely first reconstructed as a chimera of many different fossils. Thijs van Kolfschoten, a professor of mammalian paleo- and archaeozoology at Leiden University, published the below description:

The horn is most probably the "tusk" from a narwhale (Monodon monoceros), a medium-sized whale that lives in the Arctic waters around Greenland, Canada, and Russia. The left upper canine of the narwhale males form a spirally twisted, long tusk with a length up to more than 3 m. The skull of the unicorn looks like a fossil skull of a Woolly rhinoceros and the shoulder blades and the bones of the two front legs are from the extinct Woolly mammoth.

The original species to which the other bones belong is as uncertain and intriguing as the rest of the mysterious creature's history.

Reconstruction of a woolly rhino. Public Domain

Sources

Ariew, R. "Leibniz on the Unicorn and Various Other Curiosities." Early Science and Medicine, vol. 3, no. 4, Nov. 1998, pp. 267–88. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1163/157338298x00068.

Einhornhoehle / Unicorn Cave. https://einhornhoehle.de/. Accessed 16 Aug. 2022.

Fortey, Richard. "In Retrospect: Leibniz's Protogaea." Nature, vol. 455, no. 7209, Sept. 2008, pp. 35–35. www.nature.com, https://doi.org/10.1038/455035a.

Handa, Naoto, et al. "The Woolly Rhinoceros ( Coelodonta Antiquitatis ) from Ondorkhaan, Eastern Mongolia." Boreas, vol. 51, no. 3, July 2022, pp. 584–605. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1111/bor.12582.

Harsch, Viktor. "Otto von Gericke (1602-1686) and His Pioneering Vacuum Experiments." Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, vol. 78, no. 11, Nov. 2007, pp. 1075–77. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.3357/asem.2159.2007.

"Https://Twitter.Com/Brianroemmele/Status/1558807744924094466." Twitter, https://twitter.com/brianroemmele/status/1558807744924094466. Accessed 16 Aug. 2022.

"Https://Twitter.Com/Markus_macd/Status/974722895153893376." Twitter, https://twitter.com/markus_macd/status/974722895153893376. Accessed 16 Aug. 2022.

Look, Brandon C. "Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz." The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Spring 2020, Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2020. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/leibniz/.

"Thijs van Kolfschoten." Leiden University, https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/en/staffmembers/thijs-van-kolfschoten. Accessed 16 Aug. 2022.

"This 350-Year-Old Reconstruction Of A 'Unicorn' Skeleton Is Totally Hilarious." IFLScience, https://iflscience.com/this-350yearold-reconstruction-of-a-unicorn-skeleton-is-totally-hilarious-51122. Accessed 16 Aug. 2022.

"Travels through the Southern Provinces of the Russian Empire, in the Years 1793 and 1794 / Translated from the German [by F.W. Blagdon] of P.S. Pallas." Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/wtfwhr9g. Accessed 16 Aug. 2022.

Van Kolfschoten, Thijs, and Angelika Hesse. The Woolly Rhinoceros from Seweckenberge near Quedlinburg (Germany). 2021. DOI.org (Datacite), https://doi.org/10.11588/PROPYLAEUM.868.C11306.

vitoskito. "In 1663, the Partial Fossilised Skeleton of a Woolly Rhinoceros Was Discovered in Germany. This Is the 'Magdeburg Unicorn', One of the Worst Fossil Reconstructions in Human History." R/Damnthatsinteresting, 15 Aug. 2022, www.reddit.com/r/Damnthatsinteresting/comments/wovjfo/in_1663_the_partial_fossilised_skeleton_of_a/.