The large, ominous black dog has been a well-known creature in the United Kingdom’s folklore. And whether it was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s eerie Sherlock Holmes story “The Hound of the Baskervilles,” or the first appearance of Sirius Black in his shapeshifting form in the Harry Potter series, it pervaded popular culture over centuries.

The dog has many names and has numerous stories surrounding it, the best known being that it's an omen of death. In Yorkshire, it is referred to as the "Barghest," or "Bargest," or "Barguest."

According to “Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature,” the Barghest was part of the lore in northern England and particularly Yorkshire, and it was “a monstrous goblin dog, with huge teeth and claws, that appears only at night.” The encyclopedia adds:

It was believed that those who saw one clearly would die soon after, while those who caught only a glimpse would live on, but only for some months. The Demon of Tidworth, the Black Dog of Winchester, the Padfoot of Wakefield, and the Barghest of Burnely are all related apparitions. Their Welsh counterparts were red-eyed Gwyllgi, the Dog of Darkness, and Cwn Annwn, the Dogs of Hell. In Lancashire the monster was called Trash, Skriker, or Striker; in East Anglia the dog had only one eye and was known as Black Shuck, or Shock. The Manchester Barghest was said to be headless. The Barghest appears in Charlotte Bronte’s "Jane Eyre," in which the title character recalls hearing tales of a creature called Gytrash—"a North-of-England spirit…in the form of horse, mule, or large dog."

In “The Prose Brut and Other Late Medieval Chronicles: Books Have Their Histories. Essays in Honour of Lister M. Matheson,” a collection that focused on tales recorded in England in the 14th and 15th centuries and onwards, the Barghest was described also as a headless man:

Yet another possibility is that the headless man is a barghest, sometimes referred to and spelled as ‘barguest,’ ‘bahrgeist’ or ‘boguest.’ These are creatures primarily associated with the north of England—Northumberland, Durham, Yorkshire and Lancashire. They assume at will the form of a headless man, a headless lady, a white cat, a rabbit, or dog, or a black dog. The barghest is a fiend that is attached to a particular place, more often than not an isolated piece of land, a wooded area, cloughs or wasteland. The barghest is known as a portent of disaster or death for those who see it; it is also said that death may not visit the person who sees the barghest but could kill a family member instead. Medieval and post-medieval northern folklore records show that if one approaches or touches a barghest, a wound is inflicted on the person, and it will never heal.

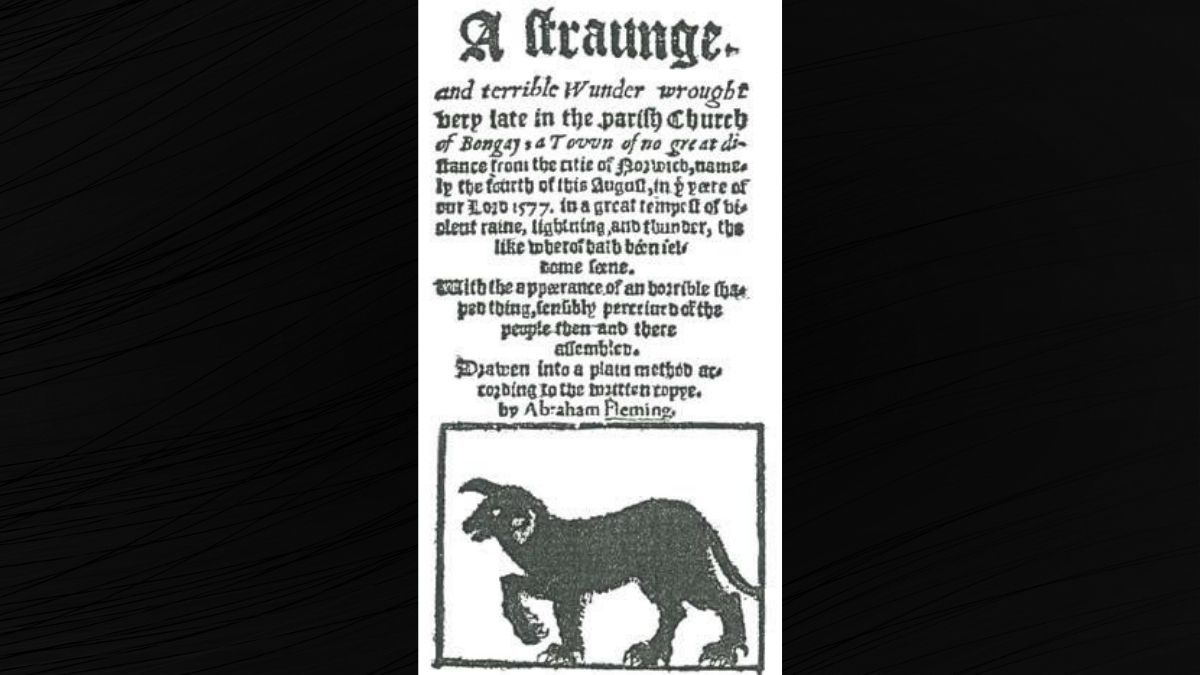

In 1578 in Suffolk, a clergyman published his account of a fearsome beast referred to as "Black Shuck" by the people of the region. In his pamphlet titled "A Strange and Terrible Wunder," he wrote:

…there appeered in a most horrible similitude and likenesse to the congregation then and there present a dog as they might discerne it, of a black colour: …This black dog or the divil in such a likenesses …passed between two persons as they were kneeling upon their knees, and occupied in prayer as it seemed wrung the necks of them bothe at one instant clene backward in so much that even at a moment where they kneeled they strangley died…

The Suffolk Archives contextualized the 1578 report:

On the 4th of August 1577 a terrible storm was raging, the sky blackened and thunder rolled. Fleming reported that a black devil dog entered the church killing two people and wounding a third. Black Shuck, the devil dog, has survived in the popular culture of Suffolk until this day. Naughty children are warned to behave lest Ole Shuck comes to get them, and Lowestoft’s finest band The Darkness started their number one album with ‘Black Shuck’. Local businesses, events and locations are still named after the Black Dog and local people are still motivated to report sightings of him.

The third book of the Harry Potter series, “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban,” introduces us to "the Grim," a black dog that appears to be following Harry, though we later learn it was his godfather Sirius Black all along, in his animal form. But in divination class, while reading tea leaves, the professor believes that Harry is cursed because she sees the shape of Grim in Harry's cup:

“The Grim, my dear, the Grim!” cried Professor Trelawney who looked shocked that Harry hadn’t understood. “The giant, spectral dog that haunts churchyards! My dear boy, it is an omen -- the worst omen -- of death!"

Harry’s stomach lurched. That dog on the cover of “Death Omens” in Flourish and Blotts—the dog in the shadows of Magnolia Crescent…

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote “The Hound of the Baskervilles,” a haunting Sherlock Holmes story in 1901, which could have been based on the “local legend of a spectral hound that haunted Dartmoor in Devonshire, England.” The victim of the story, Sir Charles Baskerville, is found dead with his face twisted in horror, and the giant paw prints of a hound were spotted near his corpse. The Baskervilles were believed to be cursed and haunted by a demonic hound that haunted their manor.

In an introduction to the Penguin Books version of “The Hound of the Baskervilles,” critic Christopher Frayling wrote:

The folklore of the British Isles is, in fact, littered with legends of phantom dogs (known as ‘black dogs’ by professional folklorists, whatever colour they happen to be), and there are still Black Dog lanes and Black Dog inns in villages all over the map. Most of these dogs are fairly benign creatures which warn of impending disaster or haunt a location where something nasty happened to their owner or their owner’s family. Many seem to have been supporters of the Stuarts, and especially King Charles I. One of them was a ghostly bloodhound from Moretonhampstead that snuffled about in a ditch opposite a pub, hunting for spilt beer. Theo Brown, a distinguished West Country folklorist affiliated to the University of Exeter who spent much of her adult life making a vast collection of black dog stories, reckoned that: ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles does not correspond with any of the black dogs known so far, and it is probably a hotch- potch of several’, a reworking of the usual commemorative or haunting function into something considerably more vicious.

Conan Doyle also acknowledged one source for the inspiration for the Hound in his preface to a later collection of his stories:

His Preface of June 1929 to The Complete Sherlock Holmes Long Stories states that: ''The Hound of the Baskervilles' arose from a remark by that fine fellow whose premature death was a loss to the world, Fletcher Robinson, that there was a spectral dog near his house on Dartmoor. That remark was the inception of the book, but I should add that the plot and every word of the actual narrative was my own.’

While pop culture appears to use the Barghest and its associated hounds frequently as sources of inspiration, we do not know of someone who actually died simply after seeing the creature. The likelihood of it being real is, frankly, pre-paws-terous.

Sources:

"B Is for Black Shuck." Suffolk Archives. https://www.suffolkarchives.co.uk/places/a-z-of-suffolk/b-is-for-black-shuck/. Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

"Barghest | British Folklore." Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/art/Barghest. Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

Doyle, Arthur Conan. "The Hound of the Baskervilles : Another Adventure of Sherlock Holmes." Penguin Books, 2001, https://archive.org/details/houndofbaskervil0000doyl_e3t8. Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

"Merriam-Webster’s Encyclopedia of Literature." Merriam-Webster, Incorporated, Publishers, 1995. Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

Rajsic, Jaclyn, et al. "The Prose Brut and Other Late Medieval Chronicles: Books Have Their Histories. Essays in Honour of Lister M. Matheson (Manuscript Culture in the British Isles)." York Medieval Press, 2016, https://books.google.com.pk/books?id=kvGjCwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false. Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

Rowling, J. K. "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban." Bloomsbury Publishing, 1999. Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

"The Hound of the Baskervilles | Summary & Facts." Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Hound-of-the-Baskervilles. Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.

"The Story behind the Hound." BBC, https://www.bbc.co.uk/devon/outdoors/moors/hound_baskervilles.shtml. Accessed 6 Dec. 2021.