Then since Jack is unfit for heaven,

And hell won't give him room,

His ghost is forced to walk the earth,

Until the day of doom:

A lantern in his hand he bears,

The way by night to show;

And, from its flame, he's got the name

Of Jack O' Lantern now.

The humble jack-o'-lantern, a pumpkin shell with a macabre face carved into it, lit from inside with a candle, is one of the most recognizable symbols of Halloween. It carries with it a rich legacy of history and folklore.

The custom itself is centuries old, though carving jack-o'-lanterns wasn't always linked specifically to Halloween, nor was the raw material always a pumpkin. In the British Isles of the 17th century, jack-o'-lanterns were made out of turnips.

One of the earliest mentions of a turnip lantern in print occurs in a letter penned in 1640 by English author James Howell, in which we find "a Turnip cut like a Death's-head with a Candle in't" credited with terrifying "Boys and Women" (though apparently no one else). The use of jack-o'-lanterns in after-dark pranks and tomfoolery was presumably widespread even before Howell's time and still in evidence 200 years later when William Holloway wrote this entry for his 1839 "General Dictionary of Provincialisms":

JACK-IN-THE-LANTHORN, s. In Hampshire, boys, of a dark night, get a large turnip and scooping out the inside, make two holes in it to resemble eyes and one for a mouth, when they place a lighted candle within side, and put it on a wall or a post so that it may appear like the head of a man. The chief end (and that a very bad one) is to take some younger boy than the rest, and who is not in the secret, to show it to him, with a view to frighten him.

By the mid-1800s, making jack-o'-lanterns was associated with Halloween, specifically, in parts of the British Isles, by which time the practice was also making its way with emigrants from Ireland and Great Britain to North America, where pumpkins took the place of turnips.

An article in an 1885 issue of Harper's Young People magazine speaks of American boys taking delight in fashioning "funny grinning jack-o'-lanterns made of huge yellow pumpkins with a candle inside" to celebrate Halloween. "Any lad skillful with a penknife can carve the eyes, nose, and wide mouth with huge teeth that seem like those of a veritable goblin when they appear suddenly at a window or adorning a gate post."

Today, of course, carving jack-o'-lanterns is for everyone, not just lads. So ubiquitous has the tradition become that in 2021, by one estimate, Americans were expected to spend at least $700 million on Halloween pumpkins to carve.

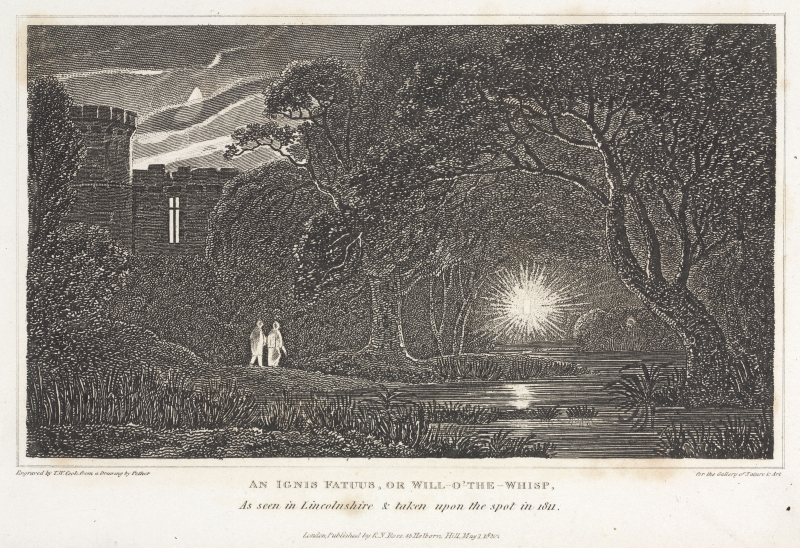

The Legend of Stingy Jack

In a sense, jack-o'-lanterns existed before the first scary face was ever carved into a vegetable. The name "jack-o'-lantern" (or, further back, "jack-with-a-lantern") was once synonymous with "will o' the wisp," or "ignus fatuus" ("foolish fire"), all these being names given to the phosphorescent lights often seen "dancing" around bogs and marshes in the darkness of night. Rather early on, learned writers understood these to be natural phenomena, probably caused by the spontaneous combustion of marsh gases, but in folklore they had long been associated with ghosts, fairies, and other supernatural entities. It was said that these these mischievous beings purposely led travelers astray in the dark, sometimes to their deaths.

One folktale links the ethereal bog lights to the fate of a ne'er-do-well named Jack who supposedly outwitted the devil at the cost of his own soul. Banned from both heaven and hell, "Stingy Jack," as he was often called by storytellers, was cursed at the end of his life to wander the earth carrying a burning ember till Judgment Day. This capsule version of Jack's story appeared in the "Annual Report and Proceedings of the Belfast Naturalists Field Club," published in 1894:

Will o' the Wisp, or Jack o' Lantern as he is called in some places, and in parts of Ireland the Water Sherrie, is a kind of malicious fairy, who, by showing a light in marshes and dangerous bogs, lures benighted travellers into danger, and sometimes to death. According to another account, he is the spirit of a man who was very wicked on earth, and also managed to trick and outwit the devil; and, in fact, made himself so feared by the prince of darkness, that after death he could not enter heaven, nor was even allowed into the other place, so afraid of him were the authorities there, and he must, therefore, wander about with his torch over dreary bogs and wastes for ever.

There are many versions of the tale, some short and some long, with the wordier variants dwelling at length on Jack's battle of wits with the devil. "The Romance of Jack o' Lantern," a poem published in 1851, and "Jack o' the Lantern," a children's story published in 1892, both begin with a description of Jack as a churlish, hard-hearted man who uncharacteristically takes pity on a stranger in need and offers him a bed for the night. The stranger turns out to be an angel who grants Jack three wishes in gratitude, though unbeknownst to our protagonist there is a catch. "Weigh well what thou asketh!" the angel warns in "Jack o' the Lantern." Jack ponders.

"I should like," said Jack, after some reflection, "that whoever shall sit in my especial chair shall never be able to lift the chair from its place nor get out of it until I allow him. I would have the hand that touches anything in my tool-box on the wall (for Jack was a cobbler) unable to move the box or take the hand out until I give him permission. Lastly, I would have woever pulls a branch from the sycamore before my door unable to let go his hold until I say so. People take my awls and pluck my tree, and I will not have it."

After looking at Jack "with sorrowful eyes and grieved expression," the angel grants his wishes and disappears, clearly disappointed with Jack's answers.

So, what was the catch?

"From that moment Jack was excluded from heaven, for he had eternal blessedness for the asking, but he asked it not." In other words, Jack will have his three selfish wishes, but he has forever forfeited his chance to go to heaven.

Fast-forward through the rest of Stingy Jack's prosperous (though loveless) life to his waning days on Earth, when there is an unexpected knock on his door. It's a minion of the devil, sent to drag poor Jack to hell. What does Jack do? He offers the devil's minion a seat. In his own chair. (Remember Jack's first wish?)

We continue with the story from "The Romance of Jack o' Lantern":

In Jack's own seat, the servant sits,

And there is fastened tight;

Jack takes his flail, and without fail,

He flogs him left and right:

And, as he scored, the flunkey roared,

At length he firmly swore,

That if set free, from thence he'd flee,

And never come back more.

Jack 1, Devil 0. The devil sends another minion.

To hell he straight must go.

Says Jack, "This brogue I first must mend;

Barefoot I could not crawl;

So put your hand in yonder box,

And hand me down my awl."Within the box he poked his hand,

And there is tightly held;

Then Jack applied his famous flair,

Until the flunkey yelled;

He yelled and roared, while old Jack scored,

Until as the first swore,

The second flunkey swore to go,

And trouble Jack no more.

Jack 2, Devil 0. His satanic majesty decides to pay Jack a personal visit.

And now the Devil came himself,

Since servants would not do;

Through Mangerton, he rose in flame,

And ordered Jack to go.

Said Jack, "My Lord, I'm ready quite,

But dead lame is old Jack;

You must get me a good stout stick,

Or take me on your back."Then from the Sycamore hard by,

The Devil seized a bough;

And fastened tight, and helpless quite,

The Devil is left now:

Jack yelled with joy, when the old boy

He saw thus in his power;

Then hastened for his famous flail,

And laid it on galore.

Now (literally) beaten, the devil promises Jack that if he lets him go, Jack will never have to go to hell. Set free, the devil departs without Jack's eternal soul.

We fast-forward again to witness Stingy Jack at the moment of his death and transformation, the birth of Jack o' Lantern, and the end of our story:

Then since Jack is unfit for heaven,

And hell won't give him room,

His ghost is forced to walk the earth,

Until the day of doom:

A lantern in his hand he bears,

the way by night to show;

And, from its flame, he's got the name

Of Jack o' Lantern now.