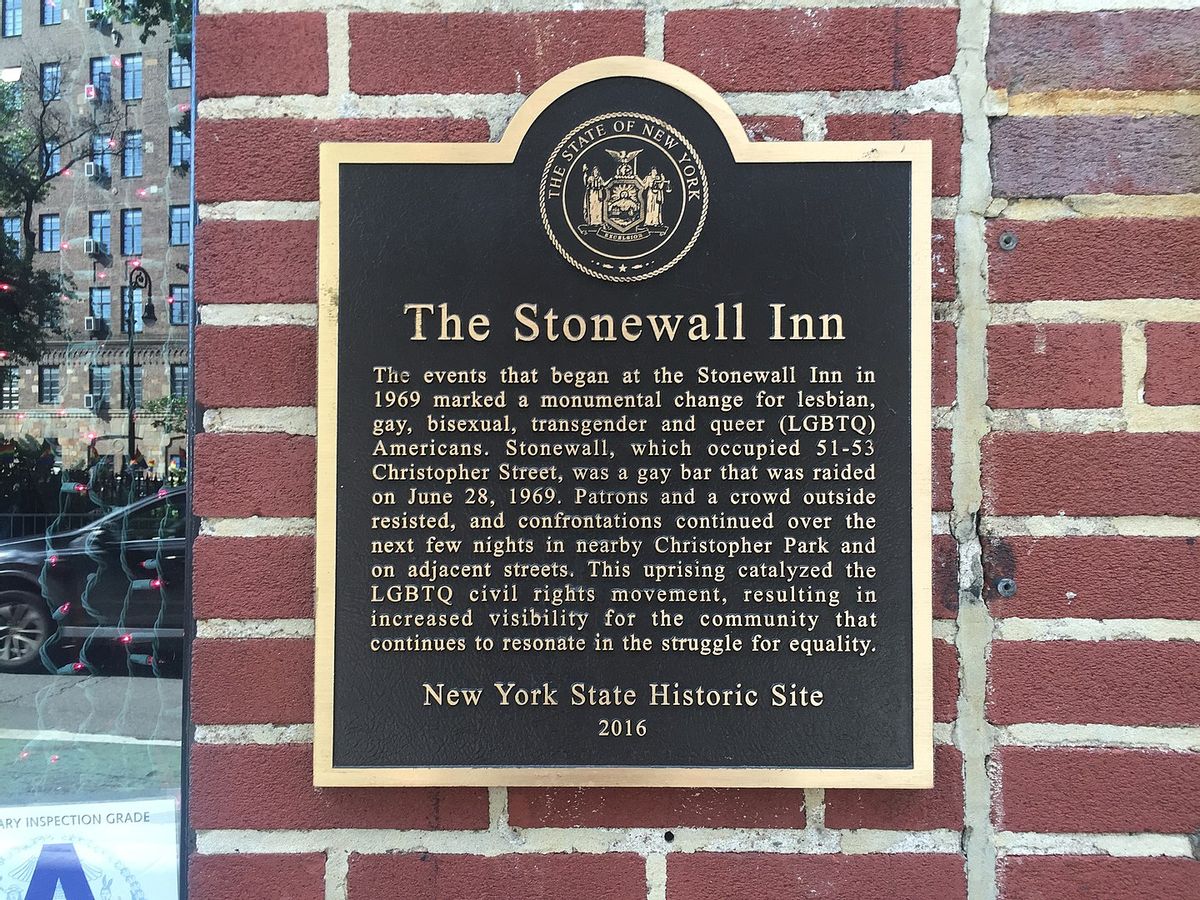

On June 28, 1969, police raided Stonewall Inn, a popular gay bar in New York City’s Greenwich Village. Resisting arrest, members of the LGBTQ community that frequented the bar began a riot that is considered a historic moment in the fight for their rights.

The spark that lit the flame of the Stonewall riots has been subject to a number of hotly debated theories over the years. One story goes that it was the funeral of actor and LGBTQ icon Judy Garland, that took place the day before, that inspired the resistance. Not everyone agrees.

The theory was suggested by a number of historians and chroniclers of the LGBTQ rights movement, and shut down by many others including people who were present during the riots.

When Garland died in 1969, she was very popular with the gay community. Culture writer Barry Walters wrote in a 1998 issue of LGBTQ magazine, The Advocate, that she was “an Elvis for homosexuals.” He wrote that Garland was “a symbol of emotional liberation, a woman who struggled to live and love without restraint. She couldn’t do it in her real life, of course, and neither could her fans. But she did it in her songs, and with them she brought along anyone who similarly dared to care too much.”

Walters also wrote: “From the way Judy fandom once united isolated, oppressed queers to the passion stirred by her passing — which may have ignited the Stonewall rebellion — Garland’s impact on gay fans is rare.”

Historian Martin Duberman, recounted in the 1994 book “Stonewall,” how Sylvia Rivera, transgender rights activist, reacted to Garland’s death, and how that night her friend Tammy Novak insisted on her going with her to Stonewall:

The first news they heard on returning was about Judy Garland's funeral that very day, how twenty thousand people had waited up to four hours in the blistering heat to view her body at Frank E. Campbell's funeral home on Madison Avenue and Eighty- first Street. The news sent a melodramatic shiver up Svlvia's spine, and she decided to become "completely hysterical." "It's the end of an era," she tearfully announced. "The greatest singer, the greatest actress of my childhood is no more. Never again 'Over the Rainbow' " — here Sylvia sobbed loudly — "no one left to look up to." No, she was not going to [Marsha P. Johnson’s] party. She would stay home, light her consoling religious candles (Viejita had taught her that much), and say a few prayers for Judy. But then the phone rang and her buddy Tammy Novak — who sounded more stoned than usual — insisted Sylvia and Gary join her later that night at Stonewall. Sylvia hesitated. If she was going out at all — "Was it all right to dance with the martyred Judy not cold in her grave?" — she would go to Washington Square. She had never been crazy about Stonewall, she reminded Tammy: Men in makeup were tolerated there, but not exactly cherished. And if she was going to go out, she wanted to vent — to be just as outrageous, as grief-stricken, as makeup would allow. But Tammy absolutely refused to take no for an answer and so Sylvia, moaning theatrically, gave in. She popped a black beauty and she and Gary headed downtown.

Rivera was a central figure during the Stonewall riots, and a major civil rights advocate. She was distraught the night of Garland’s funeral but the book does not mention if that influenced the uprising, instead stating that it merely affected Rivera’s mood that night. Novak was another key figure during the riots, she was reportedly one of the first to be arrested and who resisted the police that night.

The 1997 book “The Gay Metropolis” by Charles Kaiser, also furthered this theory, by alluding to Garland’s funeral that day:

No one will ever know for sure which was the most important reason for what happened next: the freshness in their minds of Judy Garland's funeral, or the example of all the previous rebellions of the sixties — the civil rights revolution, the sexual revolution and the psychedelic revolution, each of which had punctured gaping holes in crumbling traditions of passivity, puritanism and bigotry. All that is certain is that twelve hours after Garland's funeral, a handful of New York City policemen began a routine raid of a gay Greenwich Village nightspot, and the drag queens, teenagers, lesbians, hippies — even the gay men in suits — behaved unlike any homosexual patrons had ever behaved before.

RuPaul, drag queen, and host of “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” has also referred to the theory. The claim can be heard around five minutes into the clip below, during a 2019 segment that honored Garland:

Judy was a sensitive soul whose magnificent voice and classic films move us to this day. Now it's been fifty years since Judy passed away and on the night of her funeral in June 1969 the Stonewall riots occurred. Fed up with police harassment the patrons of the Stonewall used their grief over Judy's death to rise up and fight back and the gay liberation movement was born.

Even the critically panned 2015 film “Stonewall,” insinuated that there was a link between the two events. The film, and the theories surrounding Garland’s funeral and the riots, have been widely criticized by people who were present on that fateful night. Mark Segal, a participant at the Stonewall riots, in a 2015 article criticizing the film, also spoke out against the theory: “The most disturbing historical liberty, one brought up again and again in the film, is that Judy Garland’s death had something to do with the riots. That is downright insulting to us as a community, as inaccurate as it gets and trivializes the oppression we were fighting against.”

Another person who witnessed and participated in the riots was Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, also considered to be a foremost authority on the events of that night according to The Washington Post. “There are people who connect [Garland’s funeral] to the narrative of Stonewall, and you’re not going to tell them it doesn’t connect, so let them have it,” he told the paper in 2016. “It didn’t start the riot off, believe me.”

“Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution,” a 2004 book by David Carter, also does not give the theory much credence. Carter wrote: “No eyewitness account of the riots written at the time by an identifiably gay person mentions Judy Garland. [The] only account written in 1969 that suggests that Garland’s death contributed to the riots is by a heterosexual who sarcastically proposes the idea to ridicule gay people and the riots.”

Lanigan-Schmidt and Carter both argued that street youth who were responsible for the riot were more likely to be listening to R&B and rock, not Garland’s music.

Rachel Corbman, a fellow at the New York Historical Society who has taught classes about Stonewall, also told TIME magazine that there was no evidence connecting Garland to the Stonewall riots. “In the immediate aftermath of the event, Garland’s death and the uprising were generally not linked in firsthand accounts or the press coverage. The one exception is a sardonic quip in the coverage of the uprising in the Village Voice, which was a pretty homophobic article,” she said.

The Garland myth, according to Corbman, trivializes the myriad of serious issues that contributed to the uprising, which included abuse and harassment of the LGBTQ community, homophobia, and growing activism within the community.

Garland was an icon to the LGBTQ community, but her funeral immediately preceding the Stonewall uprising could just be a major coincidence for the history books. Whether or not participants at the riot were grieving over Garland, the fact remains that the movement was bigger and more impactful than the death of one entertainer.