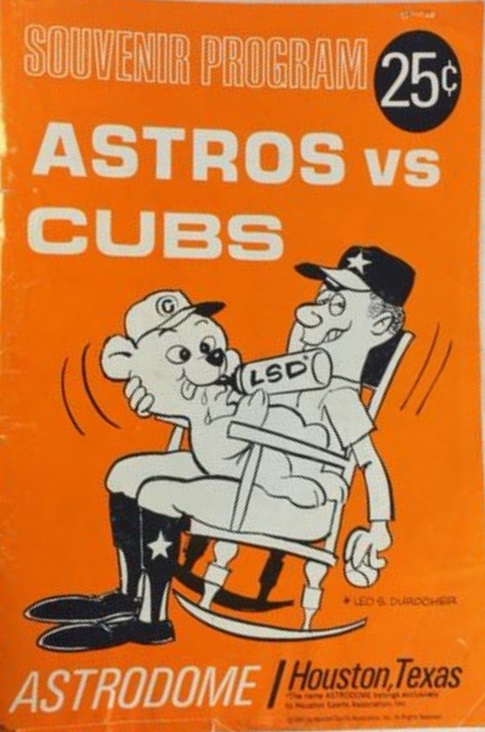

Programs sold at baseball games have always been rather staid publications, featuring scorecards, team schedules, roster listings, posed and action shots of players, and the like. But one particular Houston Astros game program from the 1966 season stands out as one of the more bizarre — not to say shocking — examples of the genre:

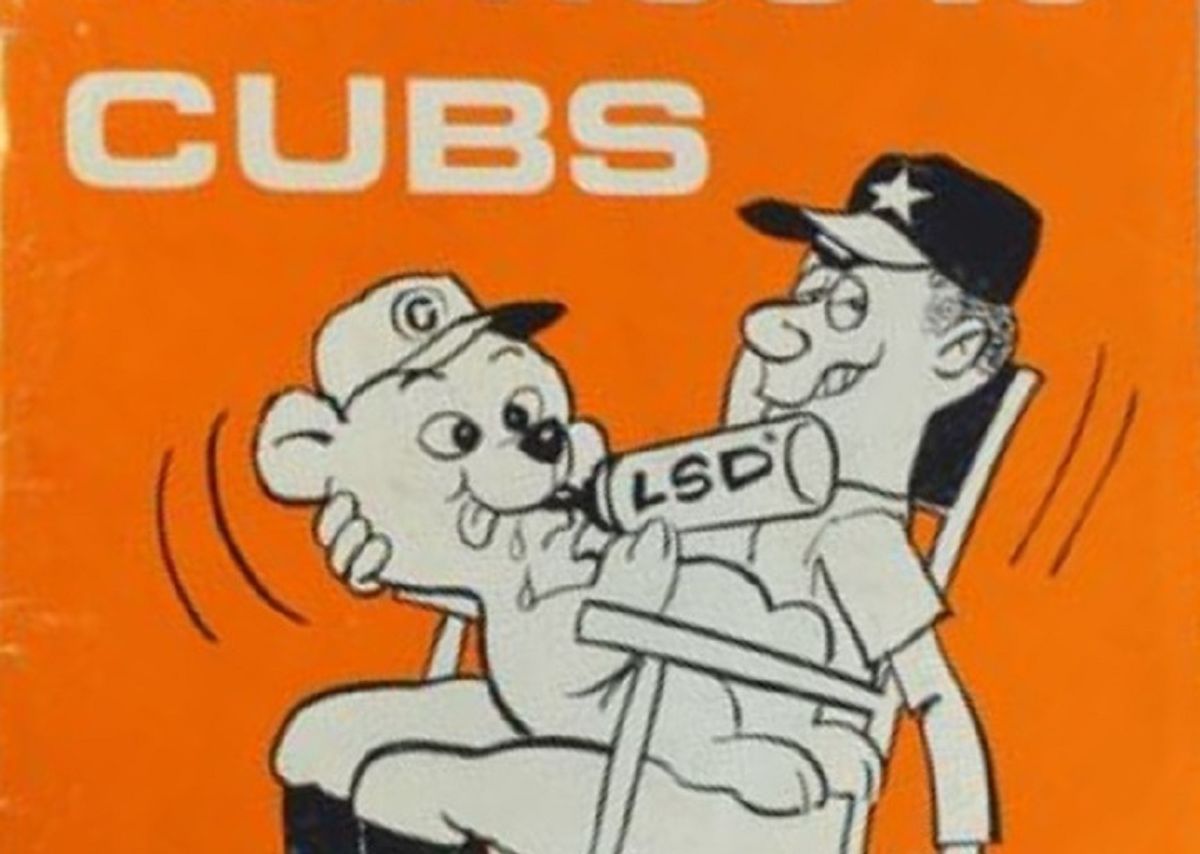

Why in the world did this publication show an Astro sitting in a rocking chair, holding on his lap a cub drinking from a bottle marked LSD? Even the mid-1960s drug culture zeitgeist can't fully explain this radical departure from conservative Major League Baseball traditions.

The answer lies in understanding what was going on with the Astros, and one particular opponent of theirs, in 1966.

The Houston franchise started out as an expansion team called the Colt .45s in 1962, playing their home games in Colt Stadium. That outdoor facility was not a desirable venue for either the team or its fans, however, for a number of reasons — primarily that it was small (seating only 33,000) and was situated in an area that was typically quite hot, humid, and full of mosquitoes.

In 1965, therefore, the team moved to the world's first domed, air-conditioned indoor stadium, dubbed the Astrodome, in the process undergoing an attendant name change from the Colt .45s to the Astros in homage to Houston's importance in the U.S. space program (as the home of NASA's Manned Space Center).

The new domed stadium was not without its problems, however. The Astrodome's ceiling featured Lucite (plexiglass) panels designed to allow sunlight into the stadium, but the glare from those panels was causing fielders to lose track of fly balls during day games. Some of the panels were painted over to cut down on the glare, but the loss of sunlight caused the stadium's natural grass to die off. The team dyed the remaining mixture of withering grass and dirt green for the remainder of the 1965 season while working to come up with a solution.

That solution was Astroturf (formerly Chemgrass), the synthetic playing surface that resembles natural grass. The team installed Astroturf in the Astrodome's infield for the start of the 1966 season, but the dyed grass-dirt mixture in the outfield wasn't replaced with artificial turf until mid-July.

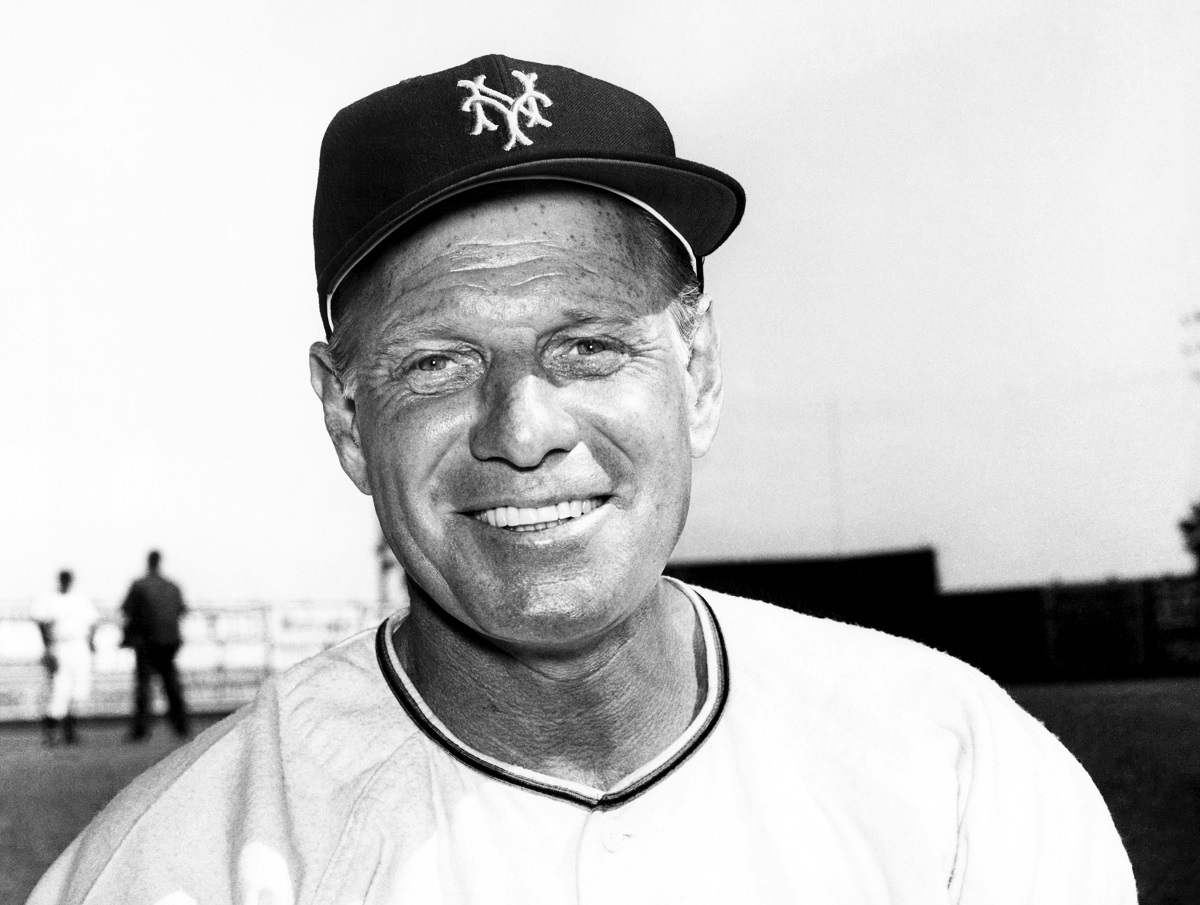

Entering into that picture was Leo Durocher, the legendarily irascible character who returned to the major leagues in 1966 after a 10-year managerial absence, as skipper of the Chicago Cubs. Leo didn't like a lot of things, and his mood wasn't improved any by the fact that the hapless Cubs finished a dreadful 59-103 (good for last place in a 10-team league) during Durocher's first year with the club.

One of the many things Leo didn't like in 1966 was the Astrodome, where his team lost eight out of nine games that year. He didn't like the stadium's half-artificial, half-dead grass playing surface. He especially didn't like its new animated scoreboard, which he felt was too much of a homer — Durocher claimed it touched off noisy displays for home runs hit by the Astros but not their opponents, that it played distracting clapping sounds while the visitors' pitcher was trying to concentrate, and that it poked fun of an injured pitcher by showing him being sent to the showers. Leo threatened to strike back at these irritants by having his players wear sneakers rather than spikes and tossing lighted firecrackers onto the field:

"I've ordered sneakers for our next trip to Houston," Leo said. "You can't grab that phony grass with spikes. I've seen their man, [third baseman Bob] Aspromonte, charge in and go astern over teakettle. You can't make quick stops on that stuff."

"What about when you come to bat?" somebody said.

"Then, we'll change into spikes," he said. "Let the umpires holler, if it takes time. I don't care. I have a right to protect my men."

"Will you do it with all the players?"

"No," said Durocher. "Just the outfielders. The infielders play on dirt most of the time. Then we're going to do something about that scoreboard of theirs, too. Wait and see."

"Like what?"

"You know how that thing goes off when one of their guys hits a home run? When the visiting club does it, nothing. That's bush. So, we'll take our own noise along. I'll bring a whole bag of firecrackers and cherry bombs, and when we hit a home run we'll light them and throw them onto the field, and if the umps say that's enough, I'll say sorry, I'm still celebrating."

"You complained in the past," somebody said, "about the clapping thing they have on the scoreboard while your man is pitching. [Astros promotions director] Bill Giles claims that the thing is never turned on while a man is in the act of pitching the ball."

Bill Giles is a liar. That's the most bust thing of all, that and the business of the shower when a pitcher is taken out of the game. They play all that sad music, and the cartoon shows the manager coming out to get him, and the guy bowing his head and walking to the shower. They made me so mad the other day with [Cubs pitcher Dick] Ellsworth. You heard about that?"

"No. What was it with Ellsworth."

"Well, he pitches the ball, and something pulls in his side. No mistaking it because he's holding his side and bending over like this after he throws the ball. I go out and signal for another pitcher, and they put this picture on [the scoreboard], with the shower. I was so mad I could have broken it."

For their part, the Astros — and their scoreboard — enjoyed thumbing their noses at Durocher for most of 1966. When the last of the Astrodome's dying natural grass was finally replaced with Astroturf at the All-Star break, the club sent a divot of turf to Leo with the suggestion that the bald manager use it to "cover his dome." (Durocher reportedly returned the package to Bill Giles along with a pound of fertilizer.) After an Astros player hit a walk-off homer in a game against the Cubs, the scoreboard flashed the message "Sorry about that, Leo." And when Houston completed a three-game sweep of Chicago in August of 1966, the scoreboard proclaimed, "Leo: baseball is a fun game."

Amidst all this tumult, when the Cubs came to Houston for a mid-season series in 1966 the game program sold at the Astrodome sported the above-referenced cover, showing a Houston Astro sitting in a rocking chair, holding on his lap a cub drinking from a bottle marked 'LSD.' An asterisk on the bottle and its accompanying footnote helpfully explained to viewers that 'LSD' stood for 'Leo S. Durocher,' thereby making the point that Durocher and his complaints were being equated with a bottle-fed crybaby. The ultimate tweak.

One small problem, though: Durocher's middle initial wasn't 'S,' as his middle name was Ernest (nor was 'S" representative of his common nickname, 'Leo the Lip').

So, how to explain the LSD reference?

At the start of 1966, LSD was a major news topic, the substance being highly controversial but not yet illegal. (It wasn't until May of that year that the first few states -- California and Nevada -- passed laws outlawing the manufacture, sale, and possession of the drug, with other states and the federal government following suit later in the year.) Almost certainly the reference to LSD in the Astros game program was an intentional play on the drug's notoriety and not a coincidence or mistake.

But how did someone in the Astros' publicity department get away with sneaking in such an overt drug reference? We can only guess that because Durocher's real middle name wasn't well known (he didn't use it himself, and he wasn't among the handful of baseball stars who were commonly known by their full names, such as Grover Cleveland Alexander), and such details weren't quite so easy to verify back in the 1960s, some sly wit in the Astros organization pulled it off by claiming Leo's middle initial was 'S,' and no one bothered to check it. And the audience, for the most part, either accepted or winked at it (depending on their level of awareness).

In an amusing irony, Durocher was dimissed by the Cubs in the middle of the 1972 season and ended his professional career as skipper of ... the Houston Astros.