In October 2017, people began sharing images on social media of a page in a Canadian elementary school workbook that indicated the forced displacement of Canada's First Nations people was a bilateral and voluntary agreement.

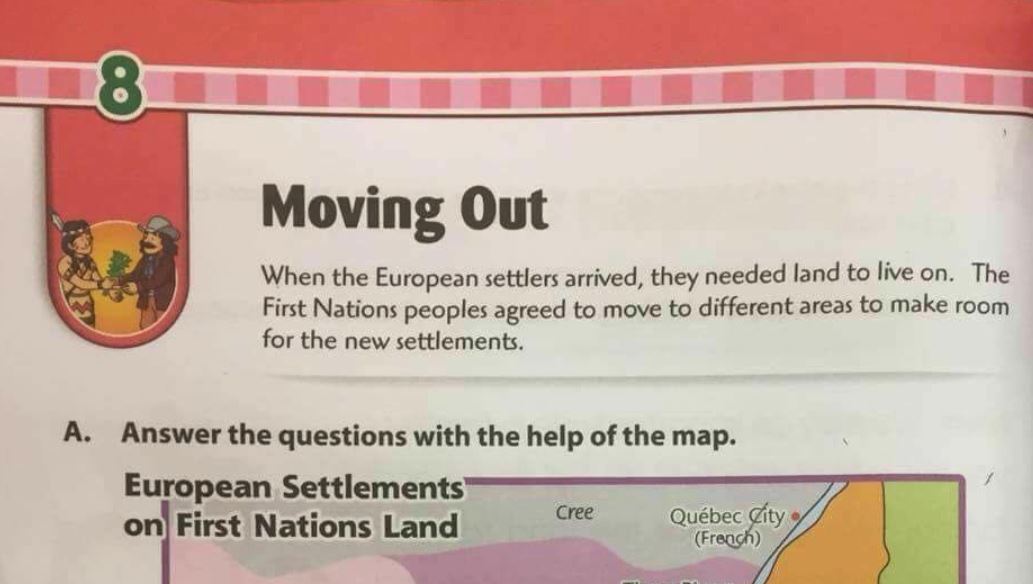

The booked contains a page headed, "Moving Out" that reads:

When the European settlers arrived, they need land to live on. The First Nations people agreed to move to different areas to make room for the new settlements.

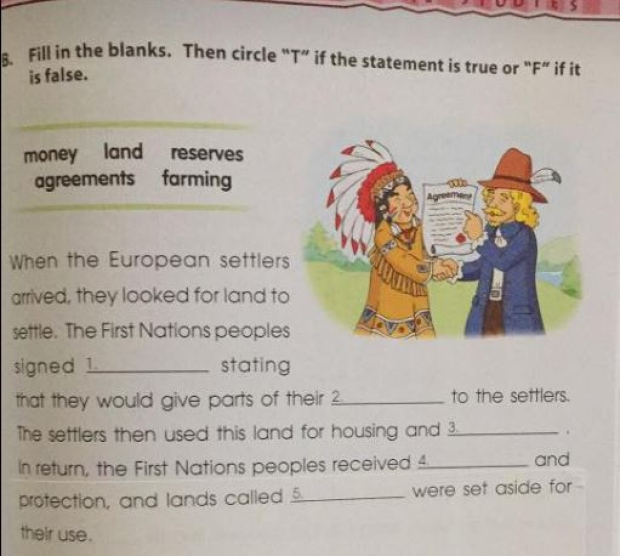

In other areas, the book informed children that First Nations peoples "moved to areas called reserves, where they could live undisturbed by the hustle and bustle of the settlers" and contained an image of a headdress-wearing indigenous man smiling and shaking hands with a white man clad in pilgrim attire, holding a paper emblazoned with the word "agreement":

The images of the book's pages, while real, give school children the grossly inaccurate notion that the brutal and tragic history of North America's indigenous peoples after European contact was nothing more than the modern equivalent of moving out of an apartment to resettle in a quieter neighborhood.

The publisher, Popular Book Company Canada, released a statement on social media saying they were issuing an immediate recall of the books. They vowed to engage First Nations communities "to assist us in understanding how best to write about this part of Canada’s history so that our materials are accurate." They also said they would be implementing a more thorough review process to ensure accuracy of published material.

Like the United States, Canada's history with its original inhabitants is far darker than smiles and handshakes. Canadian children's book author and indigenous rights activist Christy Jordan-Fenton, who has indigenous family members and writes about First Nations issues, told us:

If children can learn from very very young ages about World War I, World War II, Vietnam, Korea, the Civil War, the brutalities of slavery, the Holocaust, and the violence of armed conflict, [and when we celebrate] days like Veterans Day or Memorial Day (we have Remembrance Day here), why can Indigenous genocide not be taught, apart from the fact it punches holes in the mythos our countries are built on that holds settlers as heroes?

The indigenous peoples of North America didn't pick up their belongings and "move out" of their ancestral lands to make way for new settlers who wanted them; they were forced out. Furthermore, First Nations people in Canada only gained the right to vote in 1960 — up until the 1980s, it was commonplace for stores to post "No Indians allowed" signs.

Jordan-Fenton pointed out that it is important to teach history accurately, because it's on repeat — the taking of indigenous land and resources continues to this day. In 2016, just over the Canadian border in North Dakota, the Standing Rock Sioux bitterly fought to block an oil pipeline they fear will contaminate their sole source of drinking water. Days after taking office, President Donald Trump reversed a decision by the Obama administration, signing an executive order to complete the pipeline against the wishes of the Sioux, who consider the land through which the pipeline was built sacred.

Jordan-Fenton told us:

In Canada we have a lot of nations, especially Inuit, who never signed treaties. The treaties that were signed have been grossly misinterpreted or totally ignored. People are still being forcibly removed from their land and are fighting to keep land that’s actually technically theirs.

Teaching the truth about the brutality of history can be done at an age-appropriate level. For example, Jordan-Fenton told us that when she talks to young children about Canada's residential school system (the equivalent of the American Indian boarding schools) in which small indigenous children were taken from their parents and forced to assimilate, she leaves out the fact that many were raped and some were murdered.

Sue Caribou recounted to The Guardian the horror of such a school, having been taken from her parents' home at the age of seven in 1972:

I was thrown into a cold shower every night, sometimes after being raped.

Along with other indigenous children, she was forbidden from speaking her native tongue, Cree, called a dog, made to eat rotten food and forced to stand and sing the national anthem or be beaten.

In 2015, the Canadian government officially recognized that it had engaged in a program of cultural genocide in a description that sounds strikingly similar to the situation in the United States. It references the unilateral seizing of land:

States that engage in cultural genocide set out to destroy the political and social institutions of the targeted group. Land is seized, and populations are forcibly transferred and their movement is restricted. Languages are banned. Spiritual leaders are persecuted, spiritual practices are forbidden, and objects of spiritual value are confiscated and destroyed. And, most significantly to the issue at hand, families are disrupted to prevent the transmission of cultural values and identity from one generation to the next.

It is hardly a deal forged on a smile and a handshake.