Spring and summer 2017 saw a rash of media reports warning of the spread of a rare tick whose bite, in addition to causing skin irritation, stomach cramping, breathing problems, and other familiar tick-related symptoms in human beings, purportedly triggers an allergic reaction to red meat.

"Meet the N.J. Tick that Can Turn You into a Vegetarian," joked the headline of a story published on NJ.com in mid-May:

Lasagna. Cheeseburgers. Pizza. Ice cream.

Jerry Dotoli has enjoyed them all for most of his 73 years with no discomfort, only pleasure.

Until last December, that is. The Ocean County man had gone to Florida for the winter, where he was beset by frequent hives accompanied by a ferocious itching "four times worse than poison ivy."

After enduring one misdiagnosis after another, Dotoli finally learned from a blood test that he had become allergic to meat, pork and dairy — the very allergens he'd been happily ingesting nearly every day.

And the culprit? Most likely a bite from the Lone Star tick....

Among the dozens of similar stories published around the same time, the Williamsburg Yorktown Daily reported that tick-borne meat allergies were "on the rise" in Hampton Roads, Virginia, Minnesota Public Radio noted that a "rare, tick-triggered meat allergy" is becoming more common in northern Minnesota, and a 17 June 2017 post on popular science blog IFLScience warned that a tick responsible for causing meat allergies is currently "spreading around America":

The lone star tick, aka the “reverse zombie" tick, makes you shy away from meat rather than crave it. One bite from the tick, in fact, and you can develop a life-threatening allergy to a sugar molecule found within red meat.

Once you've been bitten, your immune system can become triggered by the presence of galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha gal) and go into overdrive. So the next time you eat meat from a mammal that produces this sugar (e.g. pork and beef), you may find yourself breaking out in massive hives or going into anaphylactic shock (if you've been bitten that is).

Apart from the attention-grabbing phrase "reverse zombie," which is new in this context, the 2017 reports echoed a spate of stories published three years earlier reporting on the same phenomenon. Common to all of them are the claims that the lone star tick is believed responsible for causing a red meat allergy and that the tick's habitat is expanding.

Although they were undeniably sensationalized, the claims are true.

Scientists have been aware for some time that the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum), first discovered in 1754, transmits pathogens associated with three rare but potentially fatal infections (Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Ehrlichia ewingii, and Borrelia lonestari), though it wasn't until the late 2000s that its connection to mammalian meat allergy (MMA for short, and also known as alpha-gal allergy), was established.

A link between tick bites and MMA was first proposed by Australian researchers who discovered that 24 of the 25 people they were monitoring for a study on meat allergies reported that they had been bitten by ticks (in Australia, the culprit was identified as the Australian paralysis tick).

At around the same time, U.S. researchers identified a specific allergen that triggered red meat reactions, a carbohydrate found in mammalian cell membranes called galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose ("alpha-gal"). Despite being aware that the geographical ranges of reported meat allergies and occurrences of the tick-borne illness Rocky Mountain spotted fever roughly coincided, it wasn't until the U.S. researchers shared a moment of pain-inspired serendipity that they narrowed down the cause:

At this time, three members of our group developed red meat allergy and each one distinctly remembered being bitten by ticks weeks or months prior to the development of symptoms. Sera from these individuals that had been obtained prior to the tick bite was compared to sera collected after the bite and it was found that serum levels of IgE to alpha-gal had increased dramatically (4 to 10-fold).

In plain English, it turned out that all three researchers had been bitten by ticks, developed red meat allergies, and experienced a dramatic increase in blood serum levels of alpha-gal antibodies, suggesting that the tick bites had triggered their sensitivity to the carbohydrate. Further research confirmed their suspicions, though questions remain about the precise mechanism by which a tick bite triggers the alpha-gal autoimmune response.

(The fascinating story of the chain of events leading to the discovery is told by the researchers themselves in "The Alpha-Gal Story: Lessons Learned from Connecting the Dots" in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology [March 2015], and also to entertaining effect in a March 2014 article by New Yorker writer Peter Andrey Smith.)

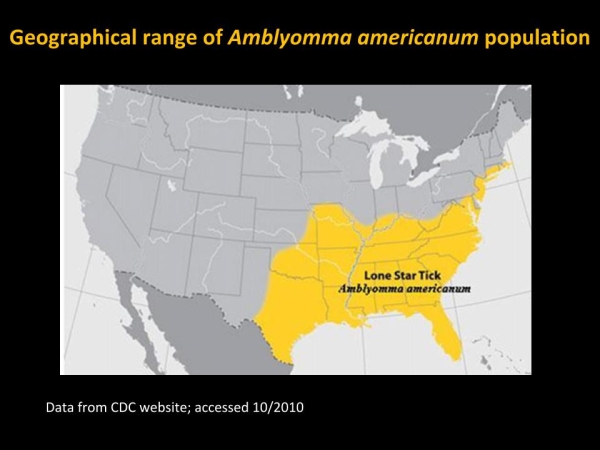

With regard to its geographical distribution, the Centers for Disease Control confirms that the lone star tick population has been on the increase for the past few decades:

The lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum, is found throughout the eastern, southeastern and south-central states. The distribution, range and abundance of the lone star tick have increased over the past 20-30 years, and lone star ticks have been recorded in large numbers as far north as Maine and as far west as central Texas and Oklahoma.

These two CDC maps shared with us by allergy researcher Dr. Scott Commins shows how the distribution of the lone star tick in the U.S. changed between 2010 and 2012:

According to the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, an allergic reaction to red meat (regardless of the specific trigger) can result in symptoms ranging from a mild case of hives to life-threatening anaphylaxis. The "good" news is that those afflicted by the MMA response can still either eat only poultry and fish or mitigate their symptoms somewhat by taking antihistamines before consuming red meat, and the allergy may recede over time; however, the immune response is generally thought to linger for life.

Although the incidence of tick-induced meat allergies remains comparatively uncommon to date, experts say, they also remind the public at large that tick bites can transmit any number of serious diseases, so a familiarity with basic tick avoidance strategies is recommended.