As controversy raged over racially motivated violence and law enforcement policies in the United States, a persistent rumor regarding the origins of 21st-century policing appeared online. It showed up, as such things tend to do, in meme form:

But how accurate is this? And where did the concept of police as de facto executors of justice (rather than peacekeepers) originate?

Law enforcement has always existed in one form or another. The first constables (from the Roman comes stabuli, or "head of the stables") with duties very similar to today's sheriffs, were around at least since the 9th century, and traveled to the Americas from Europe to supplant the systems that existed there at the time in the 1600s. The Encyclopedia of Police Science delves into the history of constables in the colonies:

In the American colonies the constable was the first law enforcement officer. His duties varied from place to place according to the needs of the people he served. Usually, the constable sealed weights and measures, surveyed land, announced marriages, and executed all warrants. Additionally, he meted out physical punishments and kept the peace.

The informal and communal system known as "the Watch" worked (more or less efficiently) on a volunteer basis in the early colonies; there were also private policing systems for hire that functioned on a for-profit basis. As populations grew, so did demands for more functional system of policing towns and cities. Volunteers would often show up to their posts drunk or not at all, and the systems were disorganized or hopelessly corrupt.

According to Gary Potter, a crime historian at Eastern Kentucky University, a centralized, bureaucratic police system did not emerge until well into the 1800s, but was quickly adopted by cities around the country:

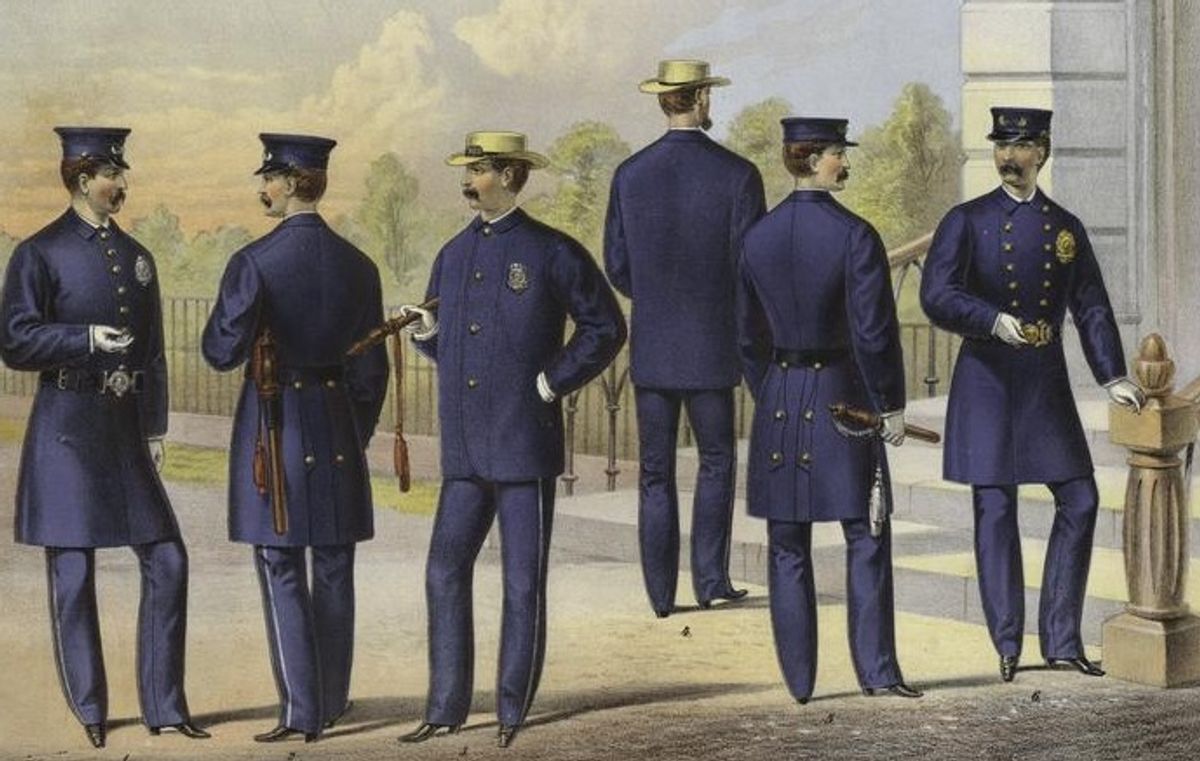

It was not until the 1830s that the idea of a centralized municipal police department first emerged in the United States. In 1838, the city of Boston established the first American police force, followed by New York City in 1845, Albany, NY and Chicago in 1851, New Orleans and Cincinnati in 1853, Philadelphia in 1855, and Newark, NJ and Baltimore in 1857 (Harring 1983, Lundman 1980; Lynch 1984). By the 1880s all major U.S. cities had municipal police forces in place.

These "modern police" organizations shared similar characteristics: (1) they were publicly supported and bureaucratic in form; (2) police officers were full-time employees, not community volunteers or case-by-case fee retainers; (3) departments had permanent and fixed rules and procedures, and employment as a police officers was continuous; (4) police departments were accountable to a central governmental authority (Lundman 1980).

More than a hundred years earlier, in 1704, the colony of Carolina developed the fledgling United States' first slave patrol. The patrol consisted of roving bands of armed white citizens who would stop, question, and punish slaves caught without a permit to travel. They were civil organizations, controlled and maintained by county courts. The way the patrols were organized and maintained provided a later framework for preventive (rather than reactive) community policing, particularly in the South:

Policing had always been a reactive enterprise, occurring only in response to a specific criminal act. Centralized and bureaucratic police departments, focusing on the alleged crime-producing qualities of the "dangerous classes" began to emphasize preventative crime control. The presence of police, authorized to use force, could stop crime before it started by subjecting everyone to surveillance and observation. The concept of the police patrol as a preventative control mechanism routinized the insertion of police into the normal daily events of everyone's life, a previously unknown and highly feared concept in both England and the United States (Parks 1976).

Patrols in the northern U.S. also became useful for breaking up labor strikes before they became too destructive (Marxist political historian Eric Hobsbawm referred to the mechanisms of violence and destruction of property to agitate for better working conditions as "collective bargaining by riot") and these services became increasingly utilized as the country became more populated and conditions simultaneously grew more difficult for the United States' restive economic underclasses.

In fact, police duties since the 1800s can be easily traced along the ebb and flow of political pressures as well as social issues:

In 1822, for example, Charleston, South Carolina, experienced a slave insurrection panic, caused by a supposed plot of slaves and free blacks to seize the city. In response, the State legislature passed the Negro Seamen's Act, requiring free black seamen to remain on board their vessels while in Carolina harbors. If they dared to leave their ships, the police were instructed to arrest them and sell them into slavery unless they were redeemed by the ship's master.

Similarly, patrols such as the Mounted Guards (forerunners to what eventually became the Border Patrol) were put in place to maintain minority quotas, among other things:

Mounted watchmen of the U.S. Immigration Service patrolled the border in an effort to prevent illegal crossings as early as 1904, but their efforts were irregular and undertaken only when resources permitted. The inspectors, usually called Mounted Guards, operated out of El Paso, Texas. Though they never totaled more than seventy-five, they patrolled as far west as California trying to restrict the flow of illegal Chinese immigration.

In March 1915, Congress authorized a separate group of Mounted Guards, often referred to as Mounted Inspectors. Most rode on horseback, but a few operated cars and even boats. Although these inspectors had broader arrest authority, they still largely pursued Chinese immigrants trying to avoid the Chinese exclusion laws.

Modern law enforcement evolved out of complex brew of a larger population, shifting sociopolitical class boundaries, and other external issues (such as the labor pressures that created an unhappy underclass) and a shift in the way policing was regarded by business owners and the population at large: proactive rather than reactive.

However, it is important to note that "the police" do not consist of a homogenous block of the American population, and while the early days of modern-day police forces are undeniable and under-covered facets of its history, the focus and perspective of policing is a complicated and fraught subject. It would be a mistake to assume that police in 2016 are the same as police in the 1870s, and to conclude that the profile of law enforcement in the United States — and around the world — has not changed throughout its existence. It would also be a mistake to assume that law enforcement cannot or will not be changed again in response to popular pressure, given that its focus has varied dramatically since its inception.