In the early days of Snopes.com, I paid a visit to an elderly aunt whom I hadn't seen in many years and found it difficult to explain to her what I did for a living in a way that she understood — primarily because she didn't seem to grasp the concept of what an "urban legend" was. I searched my memory for an example of an urban legend that she would recognize, and recalling the time and place where she grew up (i.e., the East Coast in the 1930s), I asked her, "Do you remember Uncle Don?"

Her face immediately lit up. She started to say, "I was listening the day when ..."

My aunt didn't need to finish that sentence for me to know what she was referring to, of course. Nor did she need to say anything more for me to know that she was about to regale me with her personal reminiscence of witnessing an event that never took place.

The "Uncle Don" legend was the seminal cautionary tale of the mass communications era ushered in by the advent of broadcast radio, a technology that created the potential for an injudicious remark uttered in an unguarded moment to be heard in real time by thousands of persons geographically remote from the speaker — with potential career-ending consequences:

The affable host of a radio show for children finished telling his last story of the day, wished a good night to all the youngsters in his audience, and sang his familiar sign-off ditty. As the station went to a commercial break, he leaned back in his chair, sighed, and said to no one in particular, "There, that oughta hold the little bastards!" Unfortunately for the ill-fated host, the engineer was late in cutting to the station break, and the host's disparaging remark was picked up by the still-open microphone and broadcast into millions of homes. The station was immediately flooded with thousands of telegrams from outraged listeners, and the humiliated host was fired before the day was out, never to broadcast again. Disgraced beyond redemption, he lived out the rest of his life in obscurity and died, an impoverished drunk, several years later.

Versions of this tale were familiar to many Americans in the mid-20th century, typically told by someone who claimed to have heard the infamous broadcast themselves, or who had an older friend or relative who did. At the very least, most everyone knew someone who recalled the national uproar caused by the incident or remembered reading about the firing of the hapless host in the newspaper.

This legend seems to have been attributed, at one time or another, to virtually everyone who had ever hosted a show for youngsters on radio or television. Adults who grew up in America during the years of radio's prominence between the world wars tended to name whichever local children's host they listened to or were most familiar with as the culprit. Those who grew up after television became a fixture in American households were more likely to identify one of the many ubiquitous kiddie TV personalities as the guilty party.

In one of his popular books of urban legends, folklorist Jan Harold Brunvand provided a prime example of this phenomenon. After devoting a few pages on the legend to letters debunking the notion that this incident took place on a "Bozo the Clown" television show, Brunvand offered his own recollections: "To tell the truth, I always thought that the host of my own favorite kids' radio show, 'Happy Hank' (heard in Lansing, Michigan, mid-1940s), had spoken these naughty words into a live mike."

Despite the wide variety of radio and television hosts with whom this legend has been associated, over the years one name has been connected with the alleged incident more often and more prominently than any other: Don Carney, known to millions of pre-television youngsters as "Uncle Don."

As broadcast radio rapidly gained in popularity during the early 1920s, commercial stations began creating programming specifically for children, leading to the rise of numerous radio "uncles," "aunts," and "brothers," hosts who related stories and songs and acted out skits with regular characters they invented for a largely preschool audience. These shows typically aired in the hours after school, on Saturday mornings, and in the early weekday evenings. By far the longest-lived and most well known of these children's hosts was "Uncle Don" Carney of station WOR, whose show aired throughout a seven-state area including metropolitan New York six days a week for 21 years.

Don Carney, born Howard Rice in 1897, hailed from St. Joseph, Michigan. He left home to join the circus as an acrobat and ended up in vaudeville, where, at age 15, he began using the stage name of Don Carney while performing stock Irishman parts. He traveled throughout the Midwest, performing in various stock and repertory companies before gaining minor notoriety as a trick pianist who could play while standing on his head. After bouncing from job to job and state to state, Carney eventually made his way to New York, where he obtained employment at radio stations WMCA and WOR, working as an announcer, vocal handyman, and stand-by pianist.

When a toy manufacturer came to WOR one day looking for a children's show to sponsor, Carney was tapped to audition for them. The routine he threw together in a few hours impressed the sponsors, and Don Carney soon embarked upon a new career as the beloved kiddie host "Uncle Don." His children's show made its debut in September 1928 and ran for nearly two decades (until February 1947), airing six nights a week Monday through Saturday. (At various times Carney also read the funnies to his audience of youngsters on Sunday mornings.) Uncle Don's program was a combination of original stories and songs, jokes, advice, personal messages, birthday announcements, and club news, woven around numerous commercial messages.

Even before we begin a discussion of any potential factual basis for this legend, we can already determine that the repercussion aspect of the legend — the claim that Uncle Don was fired (and, in some versions, replaced with a sound-alike) in response to his alleged careless remark — is clearly false.

Don Carney broadcast day in and day out, six and sometimes seven days a week, starting in 1928 and ending only when he finally stepped down from daily broadcasting in 1947. (Even then, he continued on with WOR as a DJ devoted to playing children’s records before moving to Miami Beach in 1948 and hosting a weekly children’s show on WKAT until his death in 1954.) His show was never canceled, and he was never taken off the air or relieved of his job for any period, until his daily spot was finally discontinued by WOR in 1947. Don Carney was never penalized for anything he said as an on-air radio personality.

We also note that not a single contemporaneous account of Don Carney’s supposed involvement in a “bastard” scandal appeared in any major news or trade publication of the day. The only articles linking the name of Uncle Don to this tale did not report it as current or recent news, but rather recounted the incident in the latter years of his career as an occurrence that had purportedly taken place at some indeterminate time in the past (a typical pattern for print accounts of apocryphal events).

In fact, we know that this Uncle Don "bastards" rumor is false, and we know exactly how it became associated with Don Carney. It was an extant legend told about a number of different children's show "uncles" and "big brothers" in the early days of broadcast radio, and — in true urban legend fashion — when Uncle Don eventually became the most famous exemplar of that form of radio host, the story gravitated to, and became permanently attached to, him.

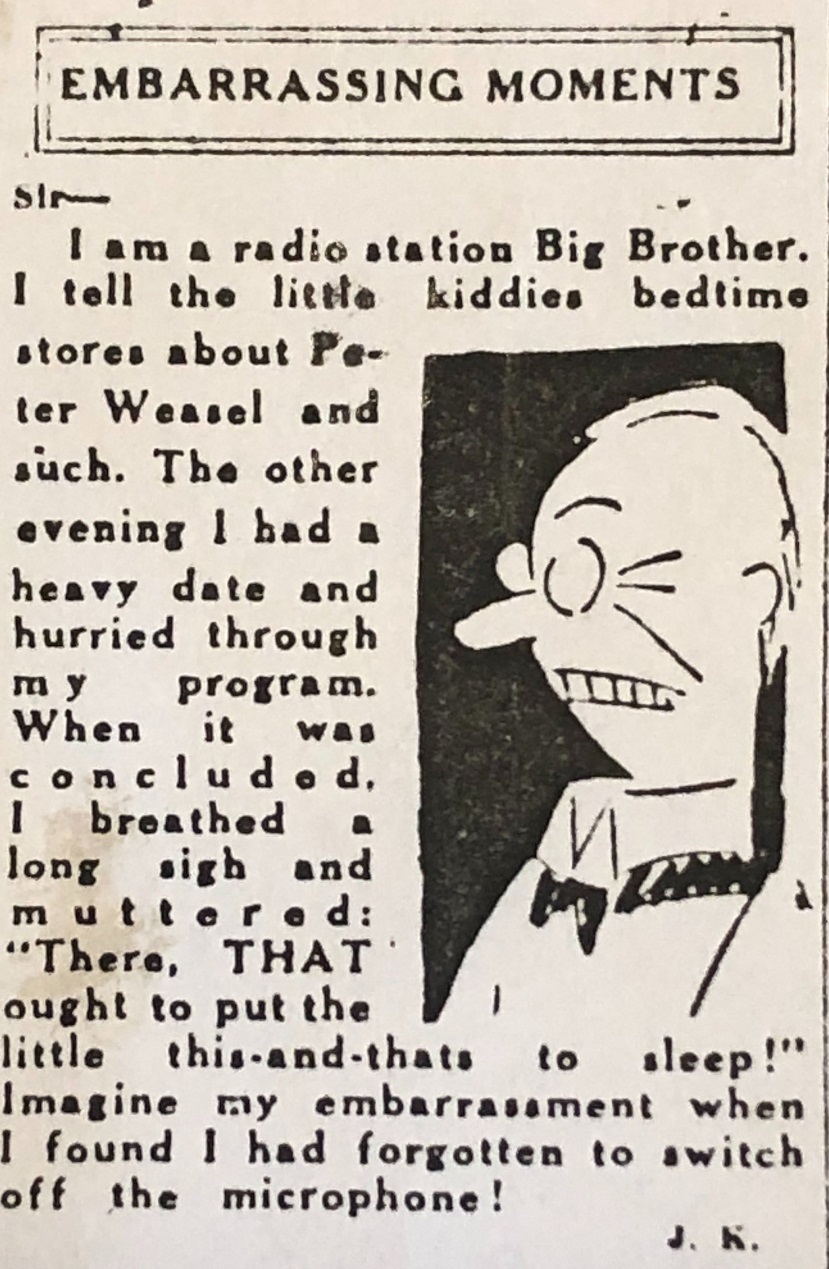

We know this because in May 1928, several months before Don Carney debuted as "Uncle Don," the very same story appeared on the front page of the Los Angeles Examiner, related in a first-person account by a "radio station Big Brother" identified only as "J.K.":

And within a few years (April 1930), the very same story was published in the entertainment industry trade publication Variety, once again attributed to a unidentified children's radio host who was clearly not Uncle Don. (Carney broadcast out of New York and not Philadelphia.) Readers at the time would have assumed the announcer referenced here was most likely Christopher Graham, known in Philadelphia as Uncle WIP:

His Error!

A wisecracking radio announcer in a Philadelphia station lost his job about two weeks ago as a result of a stern reprimand of the station by the Federal Radio Commission. Announcer had concluded a bed-time story for children and thought the power was off. For the benefit of the control room he added: ‘I hope that pleases the little b______.’

This went out over the air. Within 10 minutes several telegrams of protest, among them [some from] the Federal Radio Commission, had arrived. Others came later in bundles.

Note the many aspects of implausibility to this item. It bears a curious lack of detail for a news report of an event that supposedly happened only “two weeks ago”: no specific host was named, no particular radio station was identified, and no date was provided, even though the incident was supposedly quite recent. Moreover, it posits that telegrams of protest allegedly started arriving at the radio station “within 10 minutes,” as if the show's listeners (including members of the Federal Radio Commission, who apparently had the facilities and staff to monitor every single program on the air) lived within yards of a telegraph office and had nothing better to do that evening than pop out the door and dash off telegrams of complaint.

Unfortunately, once the "little bastards" rumor was attached to Don Carney, it clung there tenaciously for the rest of his life (and beyond), reinforced by manifestly false accounts which supposedly documented something that never took place. For example, the following narrative appeared in Sidney Skolsky’s syndicated entertainment column “Hollywood Is My Beat” on July 24, 1957:

“I’ve just run across your reference to Uncle Don’s classic blooper on radio and your bid for the exact story from a reader, who had some connection with the incident,” writes Oliver M. Sayler.

It was back in the winter of 1928-29. The station was WOR. I was in the fifth year of my weekly book and play review, “Footlight and Lamplight.” One of Uncle Don’s, programs for children immediately preceded my time on the air. I had no contact with it except, when occasionally, other studios were occupied and I was asked to broadcast in the studio he had used.

On this particular occasion, I was to follow Uncle Don on the spot, and I was standing by in his studio, waiting for the late Floyd Neal to sign him off, give the station break and introduce me. Uncle Don twittered his usual cheery wind-up, and then, not realizing that I was to follow on the same microphone, and thinking he was off the air, blurted out: “There, I hope that’ll hold the little b_______.”

Well, he wasn’t off the air! The nation-wide reaction to his blunt statement raised a furor that impaired his celebrated program. Only after a 10-year atonement and the spending of a fortune on his part to conduct a children’s entertainment concession at the N.Y. World’s Fair in 1939, did he manage to return fully to radio’s good graces. But he never again achieved his former vogue.

On the surface, this would appear to be a fairly credible account of the incident in question. It comes from someone purportedly in the broadcasting business, working at the same station as Uncle Don, and it describes a fairly specific time and place of occurrence (even if it does rely upon the amazingly fortuitous circumstance of the claimant's just happening to be in precisely the right spot, at just the right time, to witness the event).

However, this account leaves us puzzled as to how a “nation-wide reaction” could have taken place yet remain unreported in any major newspaper, magazine, or trade publication of the time. Where, then, did this national reaction play out? Moreover, a check of the radio listings in The New York Times from the winter of 1928-29 reveals that Oliver Sayler’s “Footlight and Lamplight” radio program didn’t, as he claimed, follow Uncle Don's show, but preceded it. (“Footlight and Lamplight” aired after the news at 6:15 p.m.; Uncle Don was on the air from 6:30 to 6:55 p.m.) How, then, did Sayler come to be in the studio at the conclusion of Uncle Don's program, as he claimed he was?

Despite the occasional attempts to perpetuate it in newspaper columns, this rumor might have significantly declined in prevalence after Don Carney's death (or at least been less frequently associated with his name) were it not for a series of popular "Blooper" records that rekindled public awareness of the legend. Starting the mid-1950s, writer and producer Kermit Schafer began compiling several albums of alleged boners, fluffs, and outtakes from radio and TV and issuing them in record jackets deceptively claiming that the recordings contained within were "authentic."

Although the "Bloopers" records led listeners to believe that they were hearing actual recordings of broadcast blunders, much of what Schafer presented actually consisted of fabricated "re-creations" based on (often apocryphal) secondhand sources. In this vein, Vol. 1 of the "Blooper" series presented Uncle Don front and center, in a clip of impossible clarity and audio fidelity which had clearly been staged in a modern recording studio:

Narrator: One lesson an announcer learns is to make sure he is off the air before he makes any private comment. But even the greatest sometimes slip. A legend is, Uncle Don’s remark after he had closed his famous children’s program. Let’s turn back the clock.

Radio host: (singing) Good night, little friends, good night. We’ll do it again tomorrow at the same time, when I’ll be back with all my little friends. (muffled) We’re off? I guess that ought to hold the little bastards tonight.”

https://youtu.be/PFd0_ayCTuM

Thanks to Schafer, generations of Americans too young to remember Uncle Don were left utterly convinced that he was responsible for the seminal blooper of the radio era, due to their exposure to what they thought was a "genuine recording" of a broadcast that never took place.

The “little bastards” rumor may not have ruined Don Carney’s career, but it certainly has unfairly sullied his reputation for close to a century now.

Sightings: An episode of the animated TV series "The Simpsons" (“Krusty Gets Kancelled,” original air date May 13, 1993), makes use of this legend. Believing the camera has been turned off, Gabbo, the dummy for ventriloquist Arthur Crandall, says, “That ought to hold the little S.O.B.s.”