Origin

The sculpture pictured below is real, and it was indeed crafted by an Iraqi sculptor from bronze recovered by melting down statues of former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein, but the accompanying explanatory text is quite misleading: The Iraqi sculptor was not "forced by Saddam Hussein to make the many hundreds of bronze busts of Saddam," he did not produce the memorial shown because he was "so grateful that the Americans liberated his country," and the monument was not his idea. Members of the U.S. Army paid the sculptor, who had previously worked on a few other Saddam statues, to create the work pictured according to a design of their choosing:

Example: [Collected via e-mail, 2004]

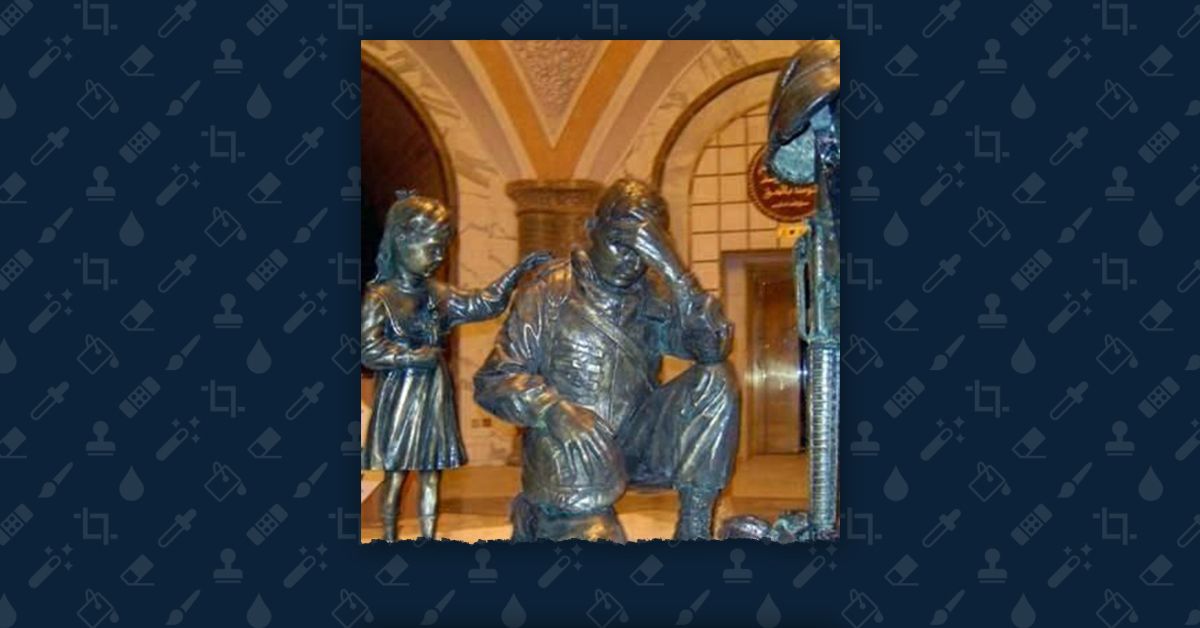

This picture of the statue was made by an Iraqi artist named Kalat, who for years was forced by Saddam Hussein to make the many hundreds of bronze busts of Saddam that dotted Baghdad. This artist was so grateful that the Americans liberated his country, he melted 3 of the fallen Saddam heads and made a memorial statue dedicated to the American soldiers and their fallen comrades. Kalat worked on this night and day for several months. To the left of the kneeling soldier is a small Iraqi girl giving the soldier comfort as he mourns the loss of his comrade in arms. It is currently on display outside the palace that is now home to the 4th Infantry division. It will eventually be shipped and shown at the memorial museum in Fort Hood, Texas.

As part of the U.S. Army's Task Force Ironhorse, the 4th Infantry Division was deployed in Iraq for most of 2003, participated in the capture of Saddam Hussein in December 2003, and saw many of their comrades killed and wounded in the violence that followed the end of major combat operations. In mid-2003, while the 4th Infantry Division was headquartered in Tikrit, Saddam Hussein's hometown, Command Sgt. Maj. Charles Fuss, the division's top noncommissioned officer, headed up a project to commemorate the unit's dead and conceived of a memorial featuring the figure of a forlorn soldier kneeling to mourn before empty helmet, boots, and rifle — an array of objects that traditionally represents a fallen compatriot:

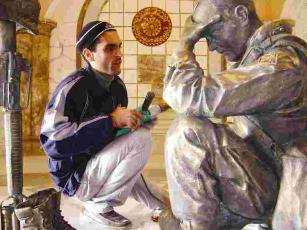

Needing a sculptor to carry out his vision, Sgt. Maj. Fuss and other Americans asked around for local talent, and an Iraqi contractor recommended a 27-year-old artist named Khalid Alussy to them. As it turned out, Mr. Alussy was one of several artisans who had worked on a pair of 50-foot bronze statues of Saddam Hussein on horseback that flanked the gateway on the main road into the presidential palace compound in Tikrit, the site of the 4th Infantry Division's temporary headquarters. Commissioned by 4th Infantry Division officers to fashion the memorial conceptualized by Sgt. Maj. Fuss, Khalid Alussy (whose first name is also rendered in English as 'Kalat') took the assignment not out love for Americans, but because he needed the money:

The officers didn't question Mr. Alussy further about his political views. Had they pressed him, they might have learned that he's harshly critical of the U.S. and bitter over an American rocket attack during the war that killed his uncle. In an interview, he says he thinks the war was fought for oil and holds the U.S. responsible for the violence and unemployment that have plagued Iraq since."I made the statues of Saddam — even though I didn't want to — because I needed money for my family and to finish my education," he says, reclining in a room decorated with several of his paintings. "And I decided to make statues for the Americans for the exact same reasons."

Mr. Alussy's initial asking price was far higher than the officers had expected. He blamed the steep price of bronze. So the Americans decided to recycle the bronze Hussein-on-horseback twins. "We figured we were going to blow them up anyway, so why not take the bronze and use it for our own statues?" recalls Sgt. Fuss. "That way we could take something that honored Saddam and use it to remember all of those we lost getting rid of him."

Without having to supply the metal, Mr. Alussy agreed to do the job for $8,000. By comparison, the former regime paid him the equivalent of several hundred dollars for his work on the Hussein statues. To finance the project, Sgt. Fuss publicized it in the task force's internal newspaper and asked officers to get soldiers to contribute $1 each. Within weeks, he raised $30,000.1

In July 2003, Army engineers blew up the two Saddam statues, cut them into pieces, melted them down, and delivered them to Mr. Alussy's house. (The delivery was done furtively in case Mr. Alussy's neighbors proved to be less than thrilled about his being in the employ of the American military.) Using a photograph of 1st Sgt. Glen Simpson as a model for the depiction of the kneeling soldier, Mr. Alussy began his work on the monument; near the end, another segment was added to his task:

As the work neared completion, Sgt. Fuss and the division's commander, Maj. Gen. Ray Odierno, decided it needed a clearer connection to Iraq. The general suggested adding a small child to symbolize Iraq's new future, Sgt. Fuss says. When they told the artist they wanted another statue, Mr. Alussy demanded $10,000 more. "He learned capitalism real fast," Sgt. Fuss says.1

After four months' worth of night and weekend labor, Mr. Alussy completed his assignment, and the statues were installed in an entranceway inside the 4th Infantry Division's headquarters in Tikrit. In February 2004 the statues were flown to the 4th Infantry Division Museum at the unit's home base of Fort Hood, Texas.

Somewhere along the line, this coda was added to the original e-mail:

Do you know why we don't hear about this in the news? Because it is heart warming and praise worthy. The media avoids it because it does not have the shock effect that a flashed breast or controversy of politics does. But we can do something about it. We can pass this along to as many people as we can in honor of all our brave military who are making a difference.

As Steve Blow of the Dallas Morning News pointed out in a later column, the Kalat story and photo ran in that paper on 27 March 2004 and was afterwards picked up and reprinted by newspapers all over the U.S.

Additional information:

| Memorial to Honor Fallen Task Force Ironhorse Troops (American Forces Press Service) |

| Changing Faces: Statue Honors Fallen Heroes (Army News Service) |

<!-- Original changelog: Last updated: 25 February 2006

16 January 2004 Updated: 16 February 2004 11 June 2004 - updated 17 October 2005 - added info about media reporting of story 25 February 2006: reformatted 16 December 2009 - updated Add'l Info links -->