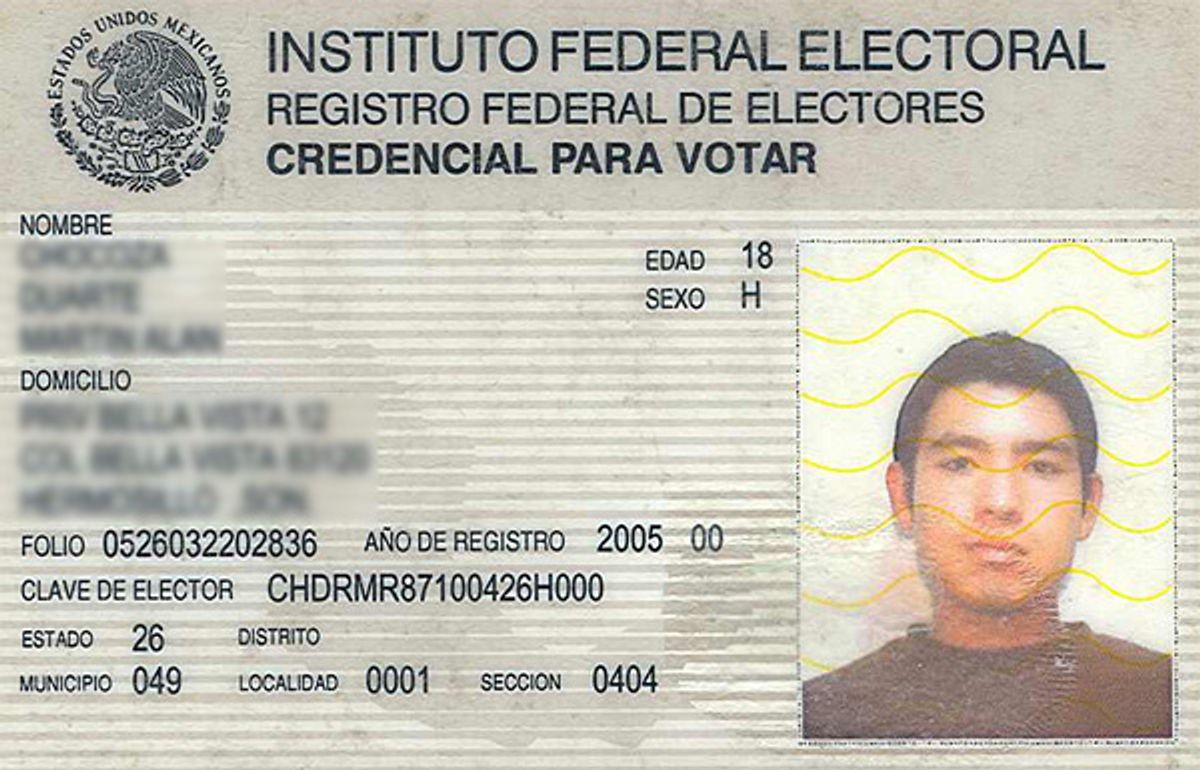

Since the 1990s, eligible voters in the country of Mexico (i.e., persons of age 18 or greater) have had to visit an electoral office and be registered into the electoral census in order to obtain a voting card issued by the National Electoral Institute (formerly the Federal Electoral Institute). Those voting cards are government-issued photo IDs, credentials that citizens are required to produce at polling stations in order to vote in federal elections in Mexico.

The United States has no equivalent national voter requirements or voter ID card, however. Some states require voters to produce photo IDs in order to vote, while others don't. And even the states that do require photo IDs may still allow voters lacking them to use other means of documenting their identities and/or to cast provisional ballots.

These differences are often cited in opinion pieces (like the meme displayed above) questioning why, if Mexico requires its citizens to produce federally-issued photo ID cards in order to vote, the United States can't or shouldn't do the same in order to crack down on voter fraud. On the other side, critics of voter ID card plans maintain there are a number of reasons why what is used in Mexico isn't necessarily a feasible solution or a panacea for the United States:

- Voter ID cards were part of reforms enacted in Mexico in the 1990s because that country had a long history of institutionalized electoral fraud and corruption, to the point that many citizens no longer trusted the electoral process nor had faith in the organization created to oversee federal elections:

During 71 years of uninterrupted Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) rule, which ended in 2000, electoral crooks known as Mapaches, or raccoons, went about stuffing and stealing ballot boxes. Stories also abound of PRI operatives plying poor voters with sandwiches and soft drinks and then escorting the recently fed to the polling stations.

Mexican officials unveiled the voting ID to properly identify electors in a country with a history of voters casting multiple ballots and curious vote counts resulting in charges of fraud — most notoriously in 1988 when a computer crash wiped out early results favoring the opposition.

The credential's widespread acceptance deepened democracy by giving credibility to the Federal Electoral Institute, analysts say. The agency was created as an independent agency to oversee federal elections.

"It's a very important prop for support of that institution," said Federico Estévez, political science professor at the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico. "What people really know about (the electoral institute) is the card."

The United States, however (contrary to common public perception) does not have such a history of widespread or concerted electoral fraud:

Five years after the Bush administration began a crackdown on voter fraud, the Justice Department turned up virtually no evidence of any organized effort to skew federal elections, according to court records and interviews.

Although Republican activists have repeatedly said fraud is so widespread that it has corrupted the political process and, possibly, cost the party election victories, about 120 people have been charged and 86 convicted as of [2006].

Mistakes and lapses in enforcing voting and registration rules routinely occur in elections, allowing thousands of ineligible voters to go to the polls. But the federal cases provide little evidence of widespread, organized fraud, prosecutors and election law experts said.

"There was nothing that we uncovered that suggested some sort of concerted effort to tilt the election," Richard G. Frohling, an assistant United States attorney in Milwaukee, said.

Richard L. Hasen, an expert in election law at the Loyola Law School, agreed, saying: "If they found a single case of a conspiracy to affect the outcome of a Congressional election or a statewide election, that would be significant. But what we see is isolated, small-scale activities that often have not shown any kind of criminal intent."

At this point, we can safely classify widespread voter fraud as a misperception — and one that is far more prevalent than the practice itself.

- As Loyola University Law School professor Justin Levitt (who has been tracking allegations of voter fraud for years) noted in 2014, voter ID requirements generally target only a single, rare form of fraud while leaving the door wide open for other (more problematic) forms:

Election fraud happens. But ID laws are not aimed at the fraud you'll actually hear about. Most current ID laws aren't designed to stop fraud with absentee ballots (indeed, laws requiring ID at the polls push more people into the absentee system, where there are plenty of real dangers). Or vote buying. Or coercion. Or fake registration forms. Or voting from the wrong address. Or ballot box stuffing by officials in on the scam.

Instead, requirements to show ID at the polls are designed for pretty much one thing: people showing up at the polls pretending to be somebody else in order to each cast one incremental fake ballot. This is a slow, clunky way to steal an election. Which is why it rarely happens.

- In Mexico, voting rules are set by the federal government. In the United States, however, even federal elections (i.e., those for President and members of Congress) are conducted on a state-by-state basis, and the various states have differing voting requirements. Thus there are no federal standards in the U.S. for determining voter eligibility, nor does the federal government have the authority to impose a single set of standards on the states.

- One of the primary reasons for the acceptance and popularity of voter ID cards in Mexico is not because they are a requirement for voting, but because they have become a practical requirement for residents of that country to use whenever proof of identity or age is required for any reason — similar to the function performed by a combination of state-issued driver's licenses and Social Security numbers in the U.S.:

The credential proved so good at guaranteeing the identification of electors that it became the country's preferred credential, one now possessed by just about every adult Mexican.

The free photo ID issued by the Federal Electoral Institute [have] become the accepted way to prove one's

identity — and [it] is a one-card way to open a bank account, board an airplane and buy beer.Voting was almost an afterthought to [Ana] MartÍnez.

"They ask for it everywhere," she said. "It's very difficult to live without it."

Ana MartÍnez says that despite getting her new card, she probably won't use it to vote. "There's no candidate worth voting for."